The War is Far from Being Over in Syria

Gilbert Achcar is Professor of Development Studies at SOAS, University of London, as well as a well-known author focusing on the Middle East and the Arab World. He met with Syrian Corner during Syria Awareness Week 2018. Achcar posits that the Syrian conflict is far from over and that for Bashar al-Assad to establish a new political framework, an accord between the US and Russia is necessary. Achcar says the role of Iran in a future Syria is one of the key issues at stake, and discusses the Turkish war against the PYD, the regional role of Saudi Arabia, the international peace conferences for Syria, the recent demonstrations in Iran, and the new US foreign policy for the Middle East in the interview below.

Assad and Putin recently declared that they have “won the war.” Is the Syrian war over? What will happen to Bashar al-Assad?

There is a lot of wishful thinking in such proclamations: battles are still raging in the Idlib region and in East Ghouta. It is true, though, that the regime, backed by Iran and Russia, has now been consolidated and is no longer facing an existential threat. Twice before, it was on the verge of a massive defeat, rescued each time by foreign intervention, first by Iran, then by Russia. As a result, the regime has now the upper hand militarily. But when I say ‘regime,’ I am actually referring to the Russia-Iran-Assad axis, as the Assad regime alone would not have been able to accomplish any of this. Far from it, it would have been defeated a long time ago.

Besides, there is still a very large area of Syria out of regime control in the North-East, dominated by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The Syrian-Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) led by the Democratic Union Party (PYD) are the SDF’s backbone. They control a huge part of Syria, comprising the whole area east of the Euphrates to the Turkish and Iraqi borders — and this is where US troops are actually involved on the ground. Two more areas are under control of the YPG and their allies: Manbij, west of the Euphrates, and Afrin where the present Turkish offensive is taking place.

Specifically addressing the issue of the YPG: Turkey has started an attack on the YPG-controlled area of Afrin. Does this represent a new escalation of the conflict?

Here lies a major contradiction. For many years, Western powers have been following their Turkish ally, a key member of NATO, in labelling the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) as a terrorist organisation. The Turkish army has engaged in several offensives against the Kurds in Turkey over the years with the support of NATO countries.

However, when the United States decided to combat ISIS in both Syria and Iraq in 2014, it did not want to involve US troops on the ground directly in the battle but provided instead air and material support to local forces. Thus, it found that the best possible ally in this battle in Syria from a military perspective would be the Kurdish forces. Washington encouraged the creation of the SDF, with the inclusion of Syrian Arabs mostly belonging to the region now under SDF control, so that the US does not appear as involved in an ethnic fight on the side of the Kurdish minority. Since everybody knows that the PYD/YPG are closely tied to the PKK, this alliance created a political paradox. In fighting ISIS, the US relied on a force that is tied to a political movement officially labelled as ‘terrorist’ by Turkey and its NATO allies, including Washington. Unsurprisingly, this has hugely irritated the Turkish state, outraged at seeing the US cooperating with its public enemy number one.

This was made even more acute by the fact that Erdogan had undergone a sharp nationalist shift in 2015 when his party, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) lost the parliamentary majority. This was due to an increase in the votes garnered by a left-wing coalition in which the Kurdish movement played a central role, but it was also due, most importantly, to losing votes to the far-right Turkish nationalists. Faced with this, Erdogan resumed the war on the Kurds after years of making peace with the Kurdish movement, resorting to whipping up Turkish nationalism. The Islamic conservative stance of his discourse did not change, but a new shift occurred in the direction of Turkish nationalism and renewed onslaught on the Kurds. Erdogan organised a second election five months later, in which his party regained a parliamentary majority. Currently the AKP is in alliance with the major far-right Turkish nationalist party.

Basically, this stance of Erdogan put him increasingly on a collision course with the US. Tensions with the Obama administration surged. Erdogan bet for a while on the Trump administration — Donald Trump promised to stop supporting the Kurdish forces in Syria. However, the Pentagon contradicted him, for the Kurdish forces have proven that they are excellent fighters and have been instrumental in defeating ISIS.

The Pentagon regards the SDF as the main card they hold today in Syria. They know that if they cut ties with the SDF, the Assad regime and Iran-led forces will inevitably try to recover the vast strategic area to the east of the Euphrates. Since the US is determined to contain Iran’s expansion in the region, the Pentagon sees no other option than to provide the Syrian-Kurdish forces and the SDF continued support. This is where the friction lies.

Erdogan is currently attacking the Kurdish-majority region of Afrin in North-West Syria. This region did play no role in the fight against ISIS and was thus no concern for the US. No US troops are present there. But Erdogan threatened to turn against Manbij — where the SDF is backed by direct US presence on the ground. Russia greenlighted the Turkish intervention in the Afrin region, withdrawing its own troops from there. Its aim is to thus exacerbate the Turkish-US rift.

This whole situation is getting even more complicated, and this is where we can reconnect to the original question: it is far from being over in Syria. Any “mission accomplished,” as Bush announced very carelessly and unwisely soon after the occupation of Iraq and as Putin has proclaimed twice about Syria, is merely wishful thinking. Nothing is solved in Syria. The Assad regime, even with Russia’s support, does not have the capacity to control the country. It needs Iran. Yet, Iran’s presence in Syria is unacceptable for both the US and Israel.

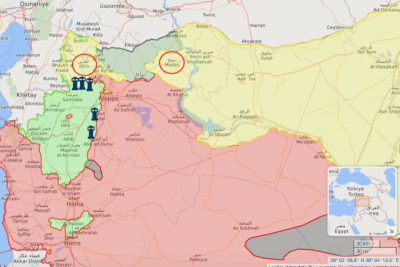

Courtesy of syria.liveuamap.com

Would Turkey, if it defeats the Kurdish forces, be willing to go as far as to occupy Manbij?

It is a very tough nut to crack indeed, and what is happening now is quite telling. It would be quite difficult for Turkish forces to remain in the Afrin region for a long time even if they manage to occupy it, as they would fall under permanent attacks. Moreover, they would be engaged in war on a foreign territory, without the excuse of being invited by the official government unlike Iran’s and Russia’s forces.

Erdogan is playing with fire. He has taken a great risk with this operation. Facing discontent even within his own party, he is using this nationalist drive to consolidate his power. But a military setback could cost him a lot.

Under what circumstances would Iran leave Syria?

Iran would need to be compelled to leave. This could happen if there is a Russian-American agreement, in the form of a United Nations Security Council resolution stipulating that, on the basis of a political agreement that would be reached in Geneva, all foreign troops that entered Syria after 2011 (excluding the Russians who were already in Syria long before that year) should leave the country.

It would be difficult for Iran to say “no,” especially if the Syrian regime is part of this deal. Assad would not side with Iran over Moscow if he had to choose. Moscow relies on his regime’s forces on the ground, while Iran is occupying the ground. Tehran would not allow the Syrian regime the same margin of autonomy as Moscow would. Add to that that the Iranian regime is ideologically quite different from the Syrian regime. The Syrian regime has been portrayed by many as a bulwark against Islamic fundamentalism even though it is propped on the ground by Iran-led Islamic fundamentalist forces. That’s also part of the complexity of this situation.

There have been some important demonstrations in Iran since the 28th of December last year. What influence on Iran’s intervention in Syria can they have?

Had the movement carried on and continued to expand, it may have created a situation compelling the regime to reconsider its intervention in Syria, which was condemned by the demonstrators. But the movement subsided and was quelled, and the regime is back in control. We see, however, a surge in the tension between the two wings of the regime. The reformist wing represented by Iranian President Rouhani is trying to curtail the hard-line wing of the Revolutionary Guard (Pasdaran), arguing that the latter and its foreign interventions are a burden on the Iranian economy.

If the social turmoil resumes, things may change, but for now the regime is in full control. Moreover, Syria is an important card in Tehran’s confrontation with the Trump administration, which threatens to cancel the nuclear agreement. Such a move would play into the hands of the hardliners and therefore encourage a continuation of Iran’s expansion as a counter movement to US pressure.

Do you think the European Union (EU) should have a bigger role in criticising Turkey for the attack on the Kurds?

The EU has failed to act independently of the United States on the global level with regard to political and military issues. It has mostly behaved until now as an auxiliary of the United States. This has become a problem for Europe with the Trump administration because it is the first time that there is a US president who is so much in contrast politically with Europe’s mainstream and so close to Europe’s far right. The Bush administration did have problems with some European governments, such as France’s and Germany’s that stood against the invasion of Iraq due to differing interests. But Tony Blair’s UK government, for instance, was fully involved on the side of Bush.

On the Palestine issue, there has been a crystallisation of a different EU opinion, which is why the President of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), Mahmoud Abbas, is now attempting to get the Europeans to recognize the Palestinian state. On Iran too, there are open divergences between the Europeans and the Trump administration. The European governments were quite happy with Obama’s policy leading to the nuclear deal with Iran, which Trump considers to be the worst agreement ever concluded by the US. If he does rescind the nuclear agreement, this will create an open crisis in US-European relations. Thus, Palestine and Iran, for the time being, are two contentious issues on which there is a sharp contrast between the US and the EU. The Syrian issue though is not one on which Europe holds views opposed to that of the US. On Syria, the EU has displayed no independent stance to this day.

Considering that the conflict is not over, do you think there is any possibility of reconstruction, as Assad is calling for?

Again, that is wishful thinking. Russia itself has on several occasions called upon the EU to fund the reconstruction of Syria. They have a lot of nerve because Russia has secured a position whereby, if there were to be a reconstruction of Syria, it would play a key role in it. Moscow would like the Europeans to fund Syria’s reconstruction with Russian companies pocketing the lion’s share of contracts. But this will not happen because the Europeans will not disburse any money without a US green light, which will not be given until Washington is convinced that Iran won’t take advantage of the situation. Under the present conditions, Iran too would necessarily secure a major part of the market. So, reconstruction won’t really be on the agenda until this whole political puzzle is solved.

Russia is trying to set a post-war political framework for Syria. They’ve started doing it at the end of 2016, shortly before Trump inaugurated his presidency. They were expecting him to deliver on his promise of new relations with Russia, but for the time being this is not happening as the establishment in Washington reacted with a strongly anti-Russian position. In any event, Trump won’t reach any deal with the Russians unless they agree to stop cooperating with Iran in Syria and push its forces out of the country.

For Trump the ideal scenario would be to reach a deal with Putin, entrust the Russians to take care of Syria on the condition that they push Iran out. In exchange for that, the United States could remove sanctions on Russia and give it some concessions in Europe. But this is clearly not on the horizon for now.

Do you think any of the talks in Sochi and Geneva will change anything in Syria?

These talks are about the conditions of a political settlement. We know more or less what this will look like — a transitional period, a new constitution, new elections, all this with Assad remaining in power and running in a new presidential election — so there’s not much new to be expected in that regard. Moscow and Assad proclaim that they are willing to have international observers monitoring new elections. They may be betting on Assad’s victory in free presidential elections today in Syria, because the Assad regime is one bloc whereas the opposition is very much divided. The fact that the opposition is in shambles may give the Assad regime enough confidence to undergo such a scenario.

However, for such a settlement to happen, an international agreement is necessary first. In the Moscow-sponsored Sochi talks, only Russia, Turkey, Iran, the Syrian regime, and a discredited part of the Syrian opposition did participate. In the UN-sponsored talks in Geneva, the United States and Europe are involved. I can’t see the US accepting an agreement that does not stipulate the withdrawal of all foreign troops that entered Syria after 2011. In other words, the US would say, “We are willing to leave Syria provided that Iranian forces leave it as well.” That’s why the US is currently sticking to the region east of the Euphrates. Washington’s message to the Russians is: “We will leave Syria to you if you get it rid of the Iranians, otherwise we won’t.”

Trump’s view of the conflict is different from Obama’s. He is trying to isolate Iran and has recognised Jerusalem as capital of the Israeli state. Why are their policies different and what implication will Trump’s policy have for the region?

There are different issues here. When it comes to Israel, Trump is catering to a specific audience: the Evangelicals and other Christian Zionists, who constituted a large part of the Republican’s constituency under Bush and are still a major part of Trump’s voter base. Mike Pence, the US Vice President, is representative of this segment. He is outbidding even his own boss in pro-Israeli discourse. Conversely, there is no consensus on this issue within the wider US establishment. Even some people in Trump’s entourage were not happy with his stance on Jerusalem, which is very ideological. The only issue on which there is a consensus in the administration is a tough attitude towards Iran, but this does not even include scrapping the nuclear agreement.

Does the Saudi regime still play any decisive role in the Syrian conflict, especially with regard to Iran?

Trump very much encouraged the Saudi rulers to escalate hostilities against Iran. They have been very clumsy in the handling of episodes such as that of putting pressure on Qatar or that of the forced resignation of Lebanon’s Prime Minister, Saad Hariri, which both ended up in fiasco. The Saudi rulers have no strategy of their own regarding Syria, they align behind the United States. The remnants of the Syrian opposition that are linked to them have been very much weakened. Thus Riyadh’s overall leverage in Syria is much weakened. Its main concern is to contain Iran and roll it back, and for that they can only rely on Washington.

This article was originally published in Syrian Corner, the SOAS Syria Society magazine.