These Teachers Refuse to Be Weaponized

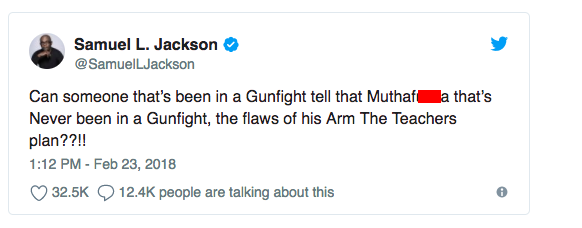

The call to “arm the teachers” started as another stink bomb President Donald Trump lobbed into the crowd at a conservative rally. But somehow, the concept cycled through the 24-hour news loop and, within a few hours, became a ubiquitous meme. Now, the morally repugnant idea of gun-toting teachers in America’s schools has taken center stage in the nation’s macabre debate on gun safety.

The idea of weaponizing teachers was incendiary bait for Trump’s base. But some progressive educators are seizing the chaotic political moment to address the deeper social problems that breed violence and fear among students. These advocates believe that achieving real “security” is not merely a matter of eliminating guns, but must also involve social transformation to promote peace within—and beyond—school communities.

Rosie Frascella, an English teacher at International High School at Prospect Heights in Brooklyn, says violence pervades her students' everyday lives, but in a different social context than the Parkland massacre. Her students face the routine brutality of oppressive policing in their streets, including the constant threat of brutality and arbitrary arrests of Black and Latino youth, as well as institutionalized segregation in the city's school and housing systems. Those everyday aggressions, along with a media culture flooded with glamorized images of violence and masculinity, pose a more present social threat than the prospect of an “active shooter” on campus. Frascella sees her job not just as a teacher, but as a “life coach”—a caregiver and trusted adult who provides emotional guidance. She doesn't want to add “security guard” to that job description.

“Our job is to deescalate, to protect, to listen, to love, care for our students," Frascella says. Achieving real safety is “not about having more security, or having more police or metal detectors,” she argues. “It's more about having more staff to be able to have one-on-one conversations, licensed therapists … who can be there, who can listen.” In Frascella’s district and across the country, many disadvantaged students have already been victimized by violence—whether it takes the form of interpersonal conflict and bullying or punishment from the criminal legal system. For young men wrestling daily with masculine identity in a culture that values patriarchy and force over care and respect, many teachers fear that more school securitization only fuels a toxic school climate.

“If we really want to stop the violence that's happening in our society,” Frascella emphasizes, “I think we need to deal with the trauma that a lot of our students are facing.”

Lois Weiner, Director of the Urban Education and Teacher Unionism Project at New Jersey City University, says that the conversation around school safety should lead with educators seeking "to frame the whole issue of these school shootings not just in terms of gun control, which has been the exclusive focus, but in terms of violence in our society.”

Under a broader framework of school safety, Weiner says, "a safe environment means people feel protected, everybody feels valued, everybody feels respected, and problems with behavior are dealt with in an appropriate way for those kids and for the people who've been harmed. It's a totally different discussion … And that's what I want to see leadership from the national unions on."

Weiner cautions against the liberal impulse to panic over mass shooting events, without confronting underlying drivers of youth violence, including cruel austerity budgets, conservative ideology that promotes inequality and a highly militarized public culture. “This is an extremely violent society,” Weiner says, “and that violence has been exacerbated by cutbacks in social services and stresses on families that are put on families and individuals.”

As civic institutions, teachers’ unions could help lead the school security conversation at a time when education is itself under attack. In West Virginia, as lawmakers across the country muse about arming school personnel, unionized teachers are mobilizing for economic justice by going on strike—demanding fair working conditions and more resources for some of the nation’s poorest school districts.

School safety should be tackled cooperatively, says Weiner, with school staff engaging the wider community by building mutual trust. Effective solutions might even originate from within communities through dialogue with young people, families and advocacy groups working together on programs to address violent situations involving youth. These programs could include restorative justice initiatives to promote conflict resolution, or reforms to security policies to limit the role of police intervention in public schools.

Rehabilitative solutions are crucial in neighborhoods where over-policing is a chief source of violence against young people. Today, even without armed teachers in classrooms, patterns of punitive brutality have inflicted disproportionate harm against children of color, as well as those with disabilities, under zero-tolerance school policing and harsh disciplinary programs. These hardline agendas have resulted in disparate expulsion rates for Black students and widespread use of forceful restraints of “defiant” children.

“The idea of arming teachers ignores the fact that in schools serving low-income kids of color, often school’s already like prison,” Weiner says.

A steroidal version of this enforcement-heavy approach in now being showcased in Florida, where lawmakers recently approved legislation aimed at deploying 37,000 trained school “marshals,” teachers deputized as armed guards, to schools across the state.

Educators warn that the further militarization of schools will almost certainly endanger more children than it protects.

As a teacher in a city known for zero-tolerance police crackdowns on young men of color in schools and on the streets, Frascella says, “Arming people is just going to create more heartbreak, and people making really poor decisions, because they haven't actually dealt with the racism or the sexism that they've been taught in society.”

Activists say that ending violence in young people’s lives isn't about locking them down but raising them up to the challenges of a hostile world. For Frascella and her fellow teachers, building peace means working with city policymakers, who have been moving to transition from zero-tolerance school-safety approaches to a more proactive concept of “school justice.” But the task of reconstructing the framework of justice in city schools is mired in the everyday challenges of chronic understaffing, academic pressure from test-driven curricula, and budgets that deprive schools of funds for basic supplies—much less extra counselors.

But there's one resource that progressive teachers can always draw upon for free: the strength that radicalized Parkland students showed as they launched massive protests and inspired waves of solidarity actions nationwide, demanding that lawmakers act to curb gun violence. "Right now, I want to just listen to the youth,” Frascella says. “I feel very inspired by the organizing that's happening, and to see so many students come out and be passionate about this issue, and really being empowered to make changes. I think that's the really beautiful thing that came out of this tragedy."

After Parkland, young people’s bravery in the face of systemic hostility offers a lesson educators and politicians can learn from. Perhaps that’s the only kind of education that can truly disarm society.

Michelle Chen is a contributing writer at In These Times and The Nation, a contributing editor at Dissent and a co-producer of the "Belabored" podcast. She studies history at the CUNY Graduate Center. She tweets at @meeshellchen.

Originally posted at In These Times.