The UK Election: A Car Crash on the Left Side of the Road

It was probably no surprise that Joe Biden announced that the huge victory for Boris Johnson and the Conservatives and the mauling defeat of Labour under Jeremy Corbyn’s radical leadership was a warning to fellow Democrats to shun the leftism of Sanders and Warren and seek safety in the political center if they hoped to beat Trump in 2020. In fact, in this nasty slugfest between the now seriously right-wing Tory party and left social democratic Labour there was little space for centrists. Despite gathering in a slice of the remain vote, the high hopes of the Liberal Democrats collapsed, their leader lost her seat to the (social democratic) Scottish Nationalists, while all the “moderate” defectors from both main parties who ran as Lib Dems, the Independent Group for Change or as independents lost badly.

It was probably no surprise that Joe Biden announced that the huge victory for Boris Johnson and the Conservatives and the mauling defeat of Labour under Jeremy Corbyn’s radical leadership was a warning to fellow Democrats to shun the leftism of Sanders and Warren and seek safety in the political center if they hoped to beat Trump in 2020. In fact, in this nasty slugfest between the now seriously right-wing Tory party and left social democratic Labour there was little space for centrists. Despite gathering in a slice of the remain vote, the high hopes of the Liberal Democrats collapsed, their leader lost her seat to the (social democratic) Scottish Nationalists, while all the “moderate” defectors from both main parties who ran as Lib Dems, the Independent Group for Change or as independents lost badly.

Thirteen of these centrist candidates (2 Lib Dems, 4 Change, and 6 independents) lost seats to Corbyn’s allegedly ultra-left Labour Party. Another 25 loudly proclaimed moderates (10 Lib Dems, 1 Change, and 14 independents) lost their seats to the Tories or withdrew before the election. Nor were self-proclaimed Labour centrists, such as Blairite Phil Wilson in Tony Blair’s old mining town seat, spared defeat at the hands of the Tories. As lefty commentator Owen Jones wrote in the Guardian, “… there is still no sign that voters have a burning appetite for centrism in any form.”

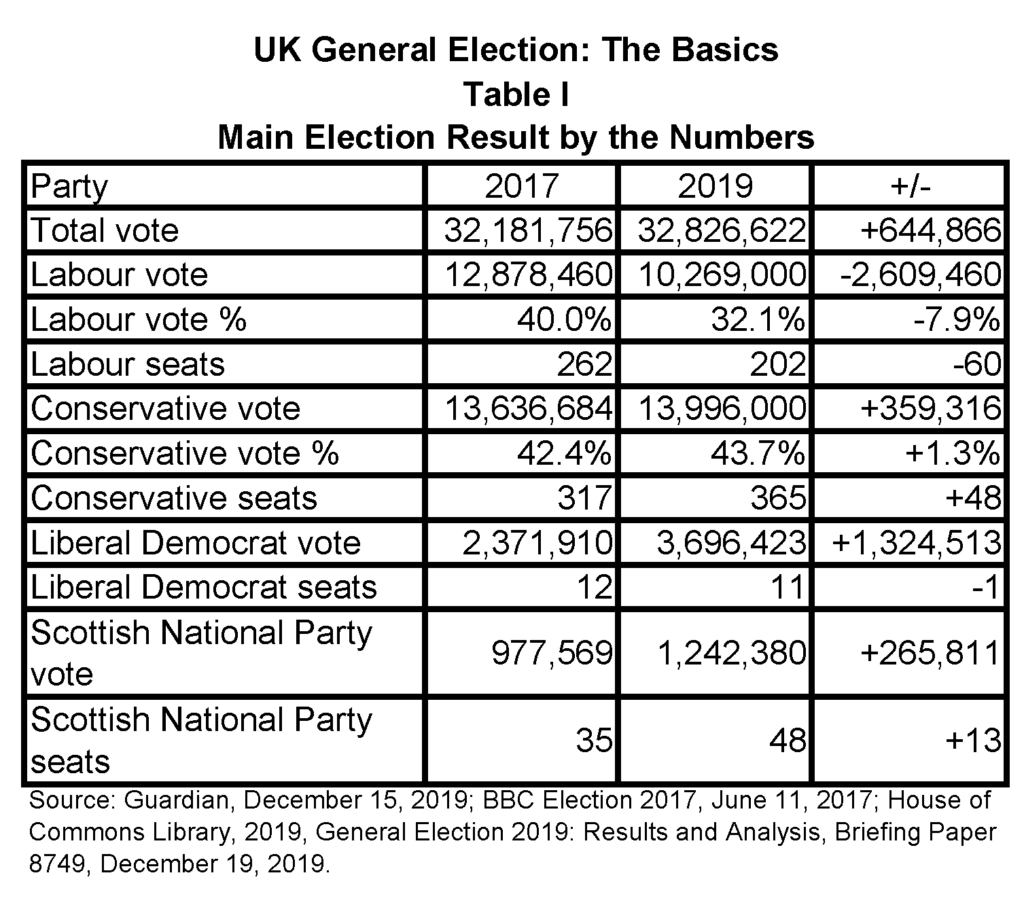

In terms of absolute losses, Labour’s decline of 2.6 million votes cost them 60 seats: 6 to the Scottish National Party (SNP), 6 to the Tories in Wales and 48 to the Tories in England, 45 of those in the old Labour heartlands of the heavily deindustrialized Midlands and North. According to YouGov’s exit poll, Labour retained 72% of its 2017 vote, with the net shift to the Conservatives amounting to 11%. Labour also lost an estimated 9% of its previous pro-EU remain voters to the Lib Dems. Some Labour votes also went to former UKIP leader Nigel Farage’s newly minted Brexit Party. These, however, are total percentages which don’t tell us where votes were won or lost. Labour’s losses to the Lib Dems was concentrated in those heavily middle class remain areas in the South of England where the Lib Dems have 6 of their 7 English seats and gained most of their 1.3 million votes. All of this would have had little or no effect on working class defections or votes in the formerly industrial Midlands and North. Labour’s lost votes that counted were mainly those in these two deindustrialized regions of England. More on this below.

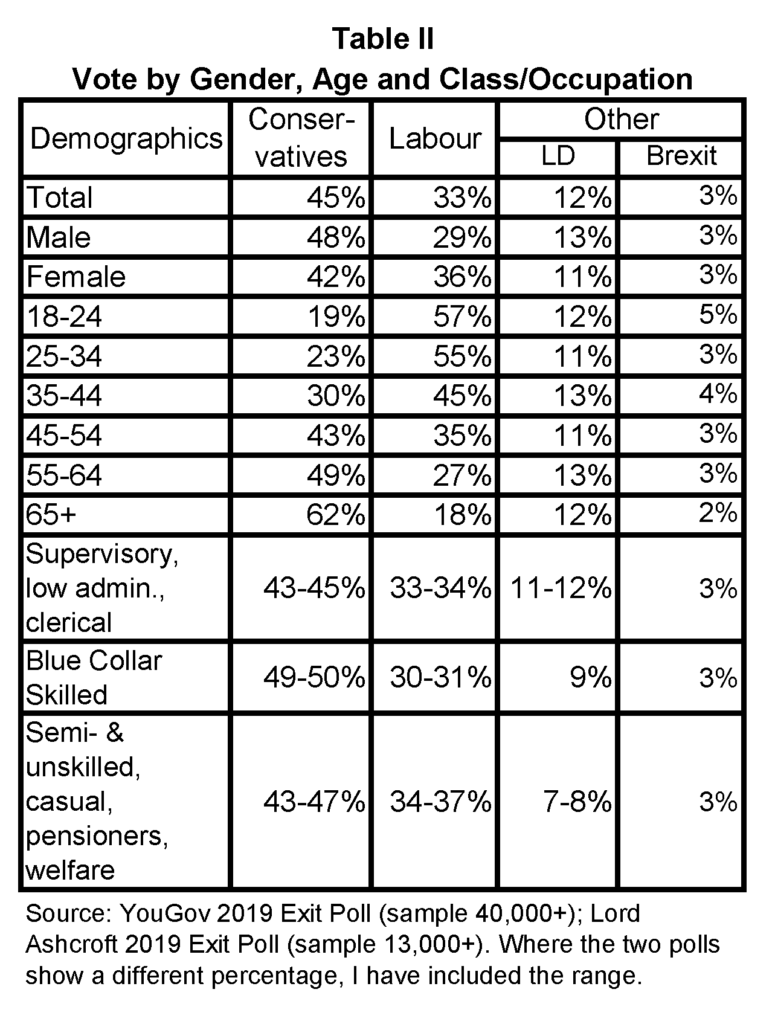

As Table II shows, the younger the voter, the more likely they were to vote Labour. Despite an upsurge in youth voter registration, however, the expected “youthquake” was more a tremor with turnout of new voters far less than expected. Indeed, a study at Brunel University showed that constituencies with a higher proportion of 18-24-year-olds had a lower turnout rate than those with fewer. Furthermore, the percentages of young people voting for Labour were lower this time than in the 2017 general election. The 18-24’s went 67% for Labour in 2017 compared to 57% this time, while 58% of the 25-34s voted Labour in 2017 compared to 55% in 2019. Voters 18 to 24 also voted at a higher rate than average for the Brexit Party.

The big tectonic shift in demographic terms was that of class, as defined here by occupation in line with the British classification system. In 2017, 39% of skilled workers voted for Labour while the semi-and unskilled and pensioner group voted Labour by 46%, compared to 30-31% and 34-37% respectively this time as Table II shows. The inescapable conclusion is that it was working class voters who made the difference. The question is why?

Analysis or blame game?

In the debate now raging in and outside the Labour Party fingers have been pointed at two major sources of blame for the defeat: Brexit and Jeremy Corbyn. The media certainly helped demonized Jeremy and his ambitious Manifesto (party program). Corbyn’s opponents blame him, his politics, and to a lesser extent his radical Manifesto. Corbyn supporters counter that it was Brexit that led traditional Labour voters who voted to leave the EU in the 2016 referendum to turn to the Tories in 2019. Indeed, the correlation between those previously Labour electoral constituencies (districts) that voted for Brexit in 2016 and Tory in 2019 is too great to doubt that this was a major factor in the shift of Labour voters to Conservative. Boris Johnson’s misleading slogan of “Get Brexit Done” not only appealed to hard core Brexiteers, but to many of those “undecided voters” weary of three years of wrangling and indecision on what to do about the EU as well.

The primary motivations for many of those who voted in favour of leaving the EU in the 2016 referendum were informed by English nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiment, but in 2019 these were reinforced by the argument that a democratic decision had been made, the people had decided. Attempts to impose another referendum on EU membership were seen as undemocratic. Furthermore, the problem of holding on to Labour’s remainers (those who voted to stay in the EU in 2016) while abiding by the 2016 vote was a serious dilemma for the party as a whole. The choice Corbyn and the leadership made in 2019 to fudge the matter by promising to negotiate a “soft” exit deal with the EU, put it to a vote (the second referendum hated by Brexiteers), and then remain neutral on how to vote alienated both remainers and leavers. It also contributed to the impression that Corbyn was an indecisive leader in a time of crisis. Labour was damned if it did and damned if it didn’t, but ultimately double damned by doing neither. So, many of Labour’s remainers voted Lib Dem, while leavers voted Tory or to a lesser extent for the Brexit Party which in parts of the North and South Wales got more than 15% of the vote.

The main criticism from Corbyn’s internal opponents wasn’t about the fudge on Brexit, however, but about Corbyn himself. The endless attacks on Corbyn from Labour centrists, magnified by both the right-wing and liberal media (Guardian and BBC included), helped convince many that Corbyn was, indeed, an ineffective leader. The evidence that Corbyn was disliked by many traditional Labour voters is strong. A poll of those who usually voted Labour but rejected it this time found that 37% blamed the leadership and 21% Brexit. Anecdotal remarks from many Labour campaigners also revealed a dislike of Corbyn among working class voters. For most such voters, of course, the only way they knew much about Jeremy other than that he was from London was through the media or from the Tories and Lib Dems who repeatedly said he was personally not fit for office and politically out of touch with moderate “hard working” England. As one Labour MP put it, “How can anyone like Jeremy when all they hear about him is bad.” The relentless campaign against Corbyn explains part of the difference between the 2017 election and this one. Labour did well in 2017 when Corbyn was relatively new and not yet thoroughly demonized, picking up both votes and seats and depriving the Conservatives of their majority. Such attacks as took place on Corbyn between his taking leadership in 2015 and the 2017 election were not enough to cost Labour seats. Yet they certainly accelerated in the last two years.

That said, in 2019 Corbyn failed to handle a number of important issues or problems well. In strategic terms the (unconscious?) decision to take the Northern working class vote for granted was a disaster. Labour’s new, enthusiastic members and those in Momentum went after marginal seats and for the most part left MP’s in the Midlands and North to their own devises. As a result, 45 of the 48 seats Labour lost in England were in the North (29) or Midlands (16). The impression that there is a London/South England bias in the leadership whether accurate or not was reinforced by this practice. To make matters worse, Jeremy’s handling of the charges of antisemitism was poor. Despite the fact that those accusing Labour of failing to take antisemitism in the party seriously or even that Labour was allegedly “institutionally antisemitic” came back again and again, Jeremy seemed perpetually unprepared to answer direct questions about antisemitism in the party or what the party was doing about it. This despite the fact that the party was processing accusations, suspending and even expelling members. Nevertheless, so poor was the leadership’s handling of this that surveys showed that many people thought that a third or more of Labour Party members were accused of antisemitic remarks or attacks, when in fact it was fewer than one percent—a proportion bad enough to require a far more satisfactory response. How many of even these incidents of alleged antisemitism were actually criticisms of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians or of Zionism, rather than anti-Jewish statements was never publicly considered.

Watching Jeremy answer tough questions on this and other matters in various TV interviews was agonizing. Corbyn supporter Owen Jones’ remark that the leadership “was often afflicted by a destructive bunker mentality” was also painfully on the mark. The presentation of the leadership’s radical program for change was haphazard and unsystematic giving the impression Labour was promising some new freebee each day in hopes of garnering votes instead of a worked-out plan for change—even though most of the individual proposals were popular. The Manifesto that finally presented the program was over a hundred pages long and also seemed more like a shopping list than a plan with the finances behind it in a separate document. As a result, the attacks on its credibility from Tories, the media, Lib Dems, etc stuck.

In the final analysis, however, I think the most fundamental problem behind Labour’s loss of much of its traditional base lay in what Corbyn and the radical movement he inspired didn’t do over the past four years. Namely, the undoing of the previous weakening of Labour’s most basic local branch and constituency organizations, on the one hand, and the technocratic centralism of the party that was the legacy of Blairism, on the other. “Reform” of the Labour Party’s structure, its relationship with the affiliated unions, and the role of the membership has been an ever changing, often confusing process for decades. Tony Blair, in line with the “Third Way” of doing things, however, knew just what he wanted from his “reforms” in the 1990s: an efficient, professionalized, centralized party machine; diminished influence for the unions; and a large, but fragmented, individualized membership.

Blair: From mass party to hollow shell

There is no doubt that since the 1980s and the deindustrialization of much of industry in Scotland, the Midlands and North of England, the old working class culture, the informal political education provided by shop stewards and (some) lefty activists, along with the intense union organization of the pit villages, steel towns, and urban “engineering” (metal working) and shipbuilding communities of these areas that supported Labour for generations has been undermined even though union density remains much higher in the North than the rest of England. This led to a sharp decline in Labour Party membership in the 1980s and contributed to a long string of electoral defeats. Tony Blair’s attempt to make the Labour Party electable, “a party of government”, involved reviving a slumping membership on a large scale, while professionalizing the party’s central apparatus as well as introducing an allegedly “realistic” neoliberal program. Flooding the party with new members and increasing the role of individual voting in electing officers and other matters was meant to dilute the influence of the left and its local activists who Blair saw as an obstacle to dumping the party’s old socialist baggage and introducing his “Third Way” political and economic program.

The model for party growth was his Sedgefield constituency in Durham’s former coal mining country which grew to 2,000 members by 1997. The national party did, indeed, grow from a little over 300,000 in 1994 to just over 400,000 in 1997, the year Blair became Prime Minister. But the influx of thousands of individual members was not the same thing as building a stronger organized base or regular engagement in community and class issues. After the initial growth the result was, as one study put it, “a significant decline in activism both in long-term members who were less participative than they had been and the new members who were less engaged in party activities than the more established participants.” The strategy produced a large, but passive and as it turned out temporary membership.

By the time Blair was replaced as party leader by Gordon Brown in 2007 the party was down to 176,891 members. Many had simply let their dues lapse, something that is much less likely to happen when there is more intense organization. No doubt his policies were behind much of this decline. The “parachuting” in of middle class candidates by Blair’s central apparatus also aliened local members. The number of constituencies with more than 500 members dropped from 132 in 1993 to 54 in 2010. The average size of a party constituency declined from 591 in 1997 to 279 in 2010. Significantly, by 2010 Blair’s Sedgefield “model” constituency party had lost 80% of its 1997 membership and the local Labour club had closed. Similarly, Gordon Brown’s Dunfermline constituency, the model of New Labour growth in Scotland, which initially tripled its membership had lost 70% of its members over this period. Presumably, other constituencies in the North and Scotland followed a similar course. This obviously contributed to the weakness that would underlie the future defeats in 2010 and 2015. What this demonstrates is that simple growth in numbers as desirable as that may be does not equate to strong, well-organized local or national party organization.

Since 2015 when Jeremy Corbyn ran for and won party leadership, Labour Party membership has soared from about 200,000 in 2014 to a high of 564,442 in December 2017. Furthermore, despite the efforts of centrist MPs, Corbyn has been elected party leader twice indicating popularity among party members for himself and the sharp left turn he proposed. Yet, evidence is strong that once again solid organization at the base did not follow numerical growth or leadership popularity. Constituency membership figures are no longer published, but it is significant that according to a survey by Queen Mary University’s party members project, 64% of those who joined between 2014 and 2017 did so via the national party rather than through a local branch or constituency organization and did so mostly at their personal initiative. Furthermore, 53% of those surveyed joined as a result of “observation of political news in the national media” rather than any efforts by the party. Contrary to some impressions, only 5% joined due to party communications on social media. Clearly growth was not a consequence of conscious, let alone systematic organizing efforts on the part of the party or its leadership.

Active participation has also been low. A 2019 report by the House of Commons Library published before the election that year found that only 23% of Labour Party members had even attended “a party meeting” (emphasis added) and only 28% had “delivered party or candidate leaflets in an election”. These may not sound so low to Americans where parties have no members and, hence, no tradition of regular participation, but they were the lowest rates of actual participation of any political party in the UK! None of this indicates organized grassroots recruitment, integration or likely retention under Corbyn’s leadership. To be sure, large numbers of new members and Momentum’s activists played an important role in the 2017 and 2019 general elections, but such relatively brief mobilizations are not the same things as participatory organization. And, indeed, by late 2019 before the election party membership had fallen by nearly 80,000 members since 2017.

There are also indications that much of the new membership comes from middle class backgrounds in the South of England. Indeed, the proportion of party members from London and the South of England has risen from 39% in 1990 to 45% in 2010 and 46% by 2017 when Labour hit its highest membership level since the 1950s. In class terms, only 23% of members are from the social categories representing Blue Collar workers of all skill levels, the unemployed, those on “welfare”, and pensioners. Despite the decline of the Blue Collar working class, these groups still represent 45-47% of the UK population: i.e., about twice their representation in the Labour Party. These are precisely the groups that compose much of the so-called “left behind” working class in the North and Midlands that Labour lost in 2019.

This was not inevitable. The Tories had been gradually gaining both votes and seats at Labour’s expense in the North and Midlands for the last couple of elections. The party leadership ignored the signs of votes lost to the Tories in 2017 when despite doing well overall, significant shifts in votes from Labour to Conservatives occurred in about four dozen constituencies that Labour held in that year. Most of these were in the North or Midlands in many places where Labour would lose in 2019. This is all the more shocking as a pamphlet entitled “Northern Discomfort” was submitted well before the election to the leadership by members of Corbyn’s own “shadow cabinet” which warned that some 50 northern seats were in danger. According to one of the authors, the pamphlet was “unwelcome and suppressed” by the leadership. (This pamphlet is not to be confused with a post-election Blairite pamphlet of the same title which blames the defeat entirely on Jeremy Corbyn.)

That much of the Midlands and the North did not receive aid or reinforcements during the 2019 election from the party’s center or its new troops, who were busy storming marginal seats rather than old “safe” Labour seats, can be seen in the complaint of an MP who lost her Greater Manchester area seat. She told the Guardian “I feel that the party was complacent about my seat. Most mornings I would have a team of half a dozen fantastic local activists. In the afternoon, I’d get two or three people and then a few more in the evening…I was eventually sent an organizer for the last few days, but it was too late.” Obviously, such a small cadre of activists is not enough to deal with a constituency that had 80,000 voters. Another MP who lost her northern seat also complained to the Guardian of a lack of support from Labour HQ and there were certainly others who felt the same.

The weakness of local organization in many of the lost constituencies shows up in the differences in regional voter turnout with the average in the South at 70% while that in the North and Midlands averaged 65%, a 5-point spread. It is further suggested by the below average turnout in over half of those constituencies lost in England in 2019. Of the 48 English constituencies Labour lost, 26 had turnout rates at least two percentage points below the average of 67.4% for England. This may sound respectable to many in the US where turnout is lower, but in Britain turnout in general elections ran above 70% from the mid-1960s through 1997 and was 69% in 2017. Some English constituencies fell near or even below 60%, while a few were below 50% in 2019.Virtually all of these were in the Midlands or North. Many of these constituencies also had a low turnout in 2017 indicating that the problem is not new or simply a result of displeasure with the party’s radical program, its leader, or even its confusing Brexit position.

Putting aside a scandal of Trumpian proportions or other unforeseeable catastrophic events the Tories will rule for five years with a solid majority. Labour in parliament can do little to stop their rampage. Corbyn will be replaced as leader, but the left may hold on to the leadership in what is already a nasty contest for a post-Corbyn party leadership. If that is the case, action on building or rebuilding a left Labour Party from the ground up needs to be a priority—even to stem the tide of slumping membership. That will have to be done in the streets and workplaces around issues that matter to local people in working class areas as well as the big issues like living standards, inequality, the NHS, climate change, etc. which, tragically, played too small a role in the general election despite Corbyn’s best efforts. On top of all of this, Labour will increasingly face a new type of “foreign” policy challenge as the United Kingdom moves past devolution toward disintegration.

Four elections and a funeral

The story above is mostly one about England rather than the UK. The 2019 British election was really four elections: one for each UK nation with distinct characteristics. The big Labour meltdown this time was largely an English affair. Of the total of 60 seats lost by Labour 48 were in England. 345 of the Tories’ 365 seats are in England. Wales saw Labour lose six seats but remain the dominant party in that small nation with 22 of its 40 seats at the Westminster parliament. On the other hand, Labour had been all but wiped out in Scotland in 2015 when it lost 40 of its 41 parliamentary seats. It regained 6 in 2017, but lost those in 2019, retaining only one seat in Scotland—a virtual funeral for Labour “north of the border” in what was once a Labour stronghold. The Labour Party as such never had a presence in Northern Ireland, which has its own distinct party system.

In Scotland and Northern Ireland social democratic leaning nationalist parties won gains. In Scotland the Scottish National Party (SNP) took 48 of that country’s 59 seats in Westminster, setting it on course for another independence referendum. In Northern Ireland, the two Irish nationalist parties, Sinn Fein with seven seats and the Social Democratic and Labour Party with two composed a majority of seats for the first time, while the “cross-community” Alliance Party took its first seat. The right-wing unionist (British nationalist) Democratic Unionists (DUP) were down to seven having lost two seats and the Ulster Unionists (UUP) with none were out of the picture This political shift has enormous implications for the future of Northern Ireland as those favoring union with Great Britain lose ground to those seeking a united Ireland.

Brexit played a role in these elections by convincing more voters that the English-dominated parties and the Westminster parliament really didn’t take their interests or concerns at all seriously. This increased nationalist sentiment toward a break with the United Kingdom. In Scotland, which had voted by 62% to remain in the EU, the imposition of Brexit by Westminster and the Tories is seen as defying the will of the Scottish people and has renewed the demand for another independence referendum. In the case of Northern Ireland, the Tories’ agreed to a border in the Irish Sea between the island of Ireland and the rest of Britain as part of the Brexit agreement with the EU. This, along with changing demographics contributed to a nationalist political majority and, for the first time ever, a slight majority (51%) in some opinion polls for uniting with the Republic of Ireland.

Although Corbyn and Labour’s “shadow chancellor” John McDonnell personally favour a united Ireland and may be sympathetic to Scottish independence on principle, the Labour Party is officially committed to preserving the “union” of the four nations of the United Kingdom. The Tories under Johnson have made it clear they will refuse Scotland a legal referendum. Just what the SNP, on the one hand, and Labour in England and Wales under a new leadership (left or otherwise), on the other, will do about this while they are also trying to resist a new era of privatization, deregulation, a “hostile environment” toward immigrants, and unequal trade with the United States is hard to imagine.

What seems clear, however, is that if the left is to keep Labour on a radical course, and at the same time make it viable in electoral terms both locally and in a future general election, the activists will need to do more than elect a new leader, fill up a left-leaning “shadow cabinet”, pump up the numbers, and take comfort in their written program. It also seems clear that dependence on one person, “The Leader”, is always a mistake, one that tends to go with electoralism and that is too frequently repeated; be it a Jeremy, a Bernie, or anyone else.

To save what was a promising movement Labour must win back and win anew the working class base its name bespeaks. This includes not only those “left behind” in the Midlands, North and elsewhere, but those in newer working class occupations around the country who are sinking into poverty and need help unionizing, as well as those in-and-out-of-work. The election season activists need to become perennial participants in branches, constituencies, unions, and workplaces who go beyond electoral mode to on-going grassroots organization, support for union struggles, and mass direct action. If, that is, the project Jeremy Corbyn almost inadvertently launched in 2015 and thousands picked up is to outlive his formal leadership.

The if signifies the reality that the precedents for transforming a social democratic party into a radical, not to say revolutionary, class-based movement are not encouraging. The demands of electoralism, further distorted by the increasing digitalization of political strategy and outreach and the built-in careerism of elected politicians, do not encourage grassroots democracy or transformational politics. Nor will the party’s center and right sit still in the face of the recent defeat or cease to believe that the electoral pot of gold lies not at the end of the rainbow, but at its center.

Still, few past efforts at changing the direction of Labour in the last few decades have seen the type or size of the influx that the party saw between 2015 and 2017. It would be a tragedy to lose the momentum (small “m”) or see this upsurge squandered either in continued mass exit or simply internal squabbling. Although this movement has taken an electoral form initially, it is, after all, part of the worldwide social and political upheaval now in progress. There are workers’ struggles to be supported, the NHS to be defended, and the planet to be saved. As left journalist Gary Younge put it mildly in the Guardian, “In a moment when we can expect a significant attack on living standards, workers’ rights, environmental protection and minorities, the left might focus more on local and national [issue] campaigns than holding positions and passing resolutions.”