The Suruç Massacre and the Reigniting of an Old Struggle

On July 20 at least thirty-two people were killed and at least 100 people were wounded by an ISIS suicide bomber. The attack took place in the Turkish town of Suruç, which stands only thirty miles away from the Syrian border. The victims, members of the Federation of Socialist Youth Associations (SGDF), were part of a 300-person contingent en route to Kobanî to assist in reconstruction efforts. The group consisted of a number of Turkish and Kurdish anarchist and socialist youth. As such, the solidaristic venture represented a major effort to create further bridges between the broader Turkish left and the Kurdish left.

There have been suggestions of Turkish collusion with the attack in Suruç. As noted in the Kurdish Question, there was considerable Turkish military presence in Suruç. Kurdish filmmaker Garip Çelik took video of the explosion, and he has asserted that it took place within the SGDF crowd. Çelik also asserts Turkish "police searched all buses carefully but skipped ours."

Whether or not Turkey colluded in some way with the attack, Turkey has capitalized on the event—as well as countering to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) killing of two Turkish police—by attacking the Kurds. Ostensibly, Turkey is entering the war against ISIS. Inside the 28-member state North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Suruç massacre has been framed as an attack on Turkey. For only the fifth time in 66 years, an Article 4 meeting was called, allowing NATO members to seek consultation when “territorial integrity, political independence or security” is found to be in jeopardy.

Yet, Turkey has concentrated most of its energy on attacking the PKK and other Kurdish groups. Patrick Cockburn asserts that it may be a tactical mistake for the United States to turn away from the Kurds so as to garner more far-reaching support from Turkey. He writes, “The U.S. will undoubtedly be able to strengthen its air offensive against ISIS, enabled to keep more planes in the skies above the self-declared caliphate because Incirlik base is only 60 miles from the Syrian border. On the other hand, about 400 U.S. air strikes were unable to prevent ISIS from capturing Ramadi, the capital of Anbar province, on May 17.”

The Turkish government is prohibiting pro-Kurdish rallies and demonstrations. Turkish authorities have arrested at least 1,300 people since the Suruç massacre — with at least 80 percent of those arrested being Kurdish or generally on the far-left. Turkey has also carried out a number of airstrikes in Iraq and Syria. Like the arrests, most of these airstrikes have targeted the Kurds. There are also reports of towns in Rojava being shelled by the Turkish military.

Arrests within Turkey and airstrikes in Kurdish Syria and Iraq constitute two fronts in the struggle — internal and external to Turkey. The arrests are an attempt to suppress rising internal dissent and opposition (the HDP). Continued airstrikes will be an attempt to destroy the infrastructure — material and institutional — that Rojava's nascent system of self-governance is built on.

Kurdish Victories in June 2015

In mid-June the struggle for Kurdish autonomy appeared to be gaining momentum. On June 7 the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) won over 13 percent of the overall vote in the Turkish general election. Almost concurrently, in Rojava, a decisive victory against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) opened up a corridor between the cantons of Cizîrê and Kobanî.

The pace of change has accelerated following the aforementioned developments as well as the breakdown of negotiations between the Kurds and Turkey over Kurdish autonomy. Since then, the Turkish state has become more overtly violent in its confrontation with the Kurds. While the Turkey-Kurd conflict holds a long violent history, from 2013 up until last month there was a ceasefire. The Suruç massacre may prove to be the catalyst for this reigniting of violent struggle between Turkey and Kurdish groups. Before engaging with these developments, it is important to briefly describe the recent efforts in building Kurdish autonomy.

Briefly Contextualizing the Current State of the Kurdish Struggle

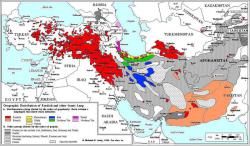

Integral to the struggle for Kurdish autonomy is the Rojava Revolution, which is taking place in West Kurdistan (a region embedded within Syria). The Rojava Revolution's most significant actor is the the Democratic Union Party (PYD). Abdullah Öcalan of PKK— himself influenced by eco-anarchist Murray Bookchin, and academics like Michel Foucault and Immanuel Wallerstein — have deeply influenced the PYD. These influences appear to have had an impact on the character of the Rojava Revolution, which possesses an explicitly feminist, anti-state and anti-capitalist character.

Also, as TATORT Kurdistan (a Kurdish activist group based in Germany) and Zaher Baher (a member of the Kurdistan Anarchists Forum) note, a vibrant movement with a similar character is underway in North Kurdistan. North Kurdistan is embedded in the Turkish state. As a result, the Kurds in the North have been unable to acquire the degree of autonomy as that gained in Rojava. In Rojava the PYD has proved capable of using the crisis in Syria to its advantage. Whereas those in Rojava have largely warded off the external threat of ISIS, the threat to Kurds in North Kurdistan is principally internal. In North Kurdistan militants must contend with the daily threat of violence and imprisonment by the Turkish state.

Seeking to transcend the national-state, capitalism and patriarchy, the Kurds and other religious and ethnic groups in North, East (embedded within Iran) and West Kurdistan seek to establish what they call Democratic Autonomy and Democratic Confederalism. In other words, the main actors of the Rojava Revolution have put economic self-management — through various types of cooperatives — and political self-governance (in the form of council democracy and assembly democracy) at its core. The Rojava Revolution appears to be largely internally defined as a revolution in gender relations, as much as it is one in economic and political relations. This is seen by the widespread presence of women's councils and women's assemblies that hold veto power over general assemblies and councils. It is also apparent in the requirement for gender parity in both general assemblies and councils.

The HDP's Historic Victory

What is written above is a broad sketch of matters I've written about in greater detail in New Politics. As noted earlier in this piece, the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) received over 13 percent of the vote in the Turkish general election. Bypassing the threshold — of 10 percent — for parliamentary representation, the HDP now holds 80 out of 550 seats in the Turkish parliament.

The HDP victory is even more significant when contrasted with the election results for Recep Tayyip Erdogan's Justice and Development Party (AKP). If the election outcome holds, the AKP will not possess a parliamentary majority for the first time since 2002. With the AKP unable to acquire a three-fifths majority, the party cannot unilaterally alter the constitution. If this majority was acquired the AKP would have been able to shift Turkey from a parliamentary to presidential system, thus transferring significant formal power to Erdogan's largely ceremonial position.

In contrast to the centralizing and nationalist tendencies of the AKP, the HDP, according to a Roar Magazine article “openly recognizes the Armenian genocide, fights for the rights of LGBT individuals, promotes the use of minority languages and has a political program stressing the need for decentralization, horizontal democracy and local autonomy.” The internal configuration of the HDP is in some ways similar to the structures emerging in Rojava. Most notably, this includes the co-chair system, in which every distinct social unit and assemblage must include both a male and female chair.

The HDP is quite libertarian (in the left-wing sense of the word) in its position on the state. For instance, in a speech, HDP co-chair Selahattin Demitras declared "We believe that the best government is the least government. We aim to make the state smaller and create a system where democracy and citizens' rights prevail." Demitras follows this with a call for radical democracy, best expressed in the assembly format. He vows that the HDP "will establish assemblies of women, youth, the disabled, belief groups, cultural and ethnic groups, farmers, workers and laborers." Throughout, though, Demitras looks to radical democracy as necessary to transforming Turkey.

With the HDP also holding itself to a standard of gender parity, its victory has helped raise the number of women in parliament to record levels. Of the eighty HDP members elected to parliament, thirty-one are women. One HDP member of parliament is the first openly gay MP in Turkey's history. A number of HDP MP's include individuals of non-Kurdish groups, including Armenians, Assyrians, and Yezidis.

Turkish Hostility to Kurdish Autonomy

While dialogue was re-opened between Erdogan and the Kurds in 2009, peace talks have stalled. Publicly, Erdogan has consistently made inflammatory remarks against the Kurds and Kurdish autonomy. Erdogan has even stated, “I am saying this to the whole world: We will never allow the establishment of a state on our southern border in the north of Syria. We will continue our fight in that respect whatever the cost may be.” Subsequently, Erdogan has called peace with the Kurds “impossible.”

While Erdogan has shown distaste for Kurdish autonomy in Syria, the HDP has also faced repression inside Turkey as well. A Jacobin article notes, “150 attacks on the HDP recorded in the weeks leading up to the elections, including: fascist mobs attacking a HDP rally with the police idly watching in Erzurum; gunshots at various HDP offices; simultaneous bombs in HDP offices in Adana and Mersin, which fortunately killed no one but left six people injured; the killing of Hamdullah Öğe, who was driving a HDP campaign vehicle; and two bombs in a huge HDP rally in Amed/Diyarbakır two days before the election, which killed four and left scores more severely injured.”

There have even been reports of Turkey assisting ISIS in the latter's fight against the Kurds. Allowing ISIS militants to freely cross within and outside of its borders has proved lethal. On June 25 ISIS infiltrated Kobanî by crossing over the Turkish border into Syria. The attack resulted in over 200 deaths. According to The Guardian, Turkey was purchasing oil from ISIS at a rate of $1m-4m per day. In the same report, an unnamed Western official stated that links between ISIS and Turkey are “undeniable.”

The official went on to say, “There are hundreds of flash drives and documents that were seized there. They are being analyzed at the moment, but the links are already so clear that they could end up having profound policy implications for the relationship between us and Ankara.”

The AKP government has also blocked the funneling of humanitarian aid into Rojava. Thus, immediately following its electoral success the HDP was looking to voice a serious call for recognition of the three Cantons of Rojava, as well as secure steady passage of aid. Yet, the situation has become significantly complicated and has intensified. Securing passage of aid is off the table. The question of recognition is no longer a matter up for negotiation. Instead, it appears this question is returning to the battlefield.

With Turkey still being ruled by an interim government, new elections are imminent. With massive arrests of Kurdish activists, it will be difficult for the HDP to reproduce its historic victory. With nationalism fueled, the AKP could reach the three-fifths majority needed to alter the constitution. As a result, the Kurds would lack a voice in Turkish parliament, removing a powerful tool for achieving recognized Kurdish autonomy.

One wonders if this may be a step back in the fight against ISIS. Motivated by a desire to carve out its own post-state self-governing polity, the Kurds have far more to gain from victories against ISIS. Given its relationship with ISIS, Turkey's investment in seeking to defeat ISIS is questionable. Turkey contains far greater military capacity than the Kurds. Yet, thus far it appears that the majority of Turkey's military might is being spent on weakening the Kurds rather than striking any significant blows on ISIS. In this fight, Turkey's geopolitical position is at stake. For the Kurds, their very survival is on the line—in jeopardy both from ISIS and Turkey, as Suruç showed.

Declarations of Self-Government Across Turkey

As part of the back-and-forth nature of the struggle, Kurdish militants within Turkey have responded. Some of the response has included women forming self-defense brigades. And the response has not simply been military; there has been a wave of declarations of autonomy by groups in various regions. This wave is sweeping across Turkey but is particularly strong in North Kurdistan (southeast Turkey). According to JINHA, “the towns and neighborhoods that have declared self-government are Silopi; Cizre; Batman's Bağlar neighborhood; Diyarbakır's Sur district; Lice; Silvan; Varto; Bulanık; Yüksekova; Şemdinli; Edremit; Van's Hacıbekir neighborhood; Istanbul's Gazi neighborhood; and Doğubeyazit.”

Many of the declarations of autonomy have been issued by people's assemblies. Such declarations have, at minimum, meant that these towns and neighborhoods no longer recognizing the Turkish state. Similar to the libertarian socialist orientation of Rojava, this rejection of the state has not simply meant rejecting Turkey, but rejecting the state-as-such. As a result of these declarations, however, a number of activists have been detained.

Furthermore, the declarations of autonomous self-governance and the rapid mobilization reflect the increased political capacity of Kurdish groups in North Kurdistan. With the ideological shift of the PKK, Kurdish groups have invested themselves in a more participatory democratic framework for a number of years now. In the last decade this has meant the spread of more libertarian socialist propaganda, as well as trainings, workshops, and micro-institution-building in North Kurdistan that is based in participatory democratic practice. With the struggle reignited, this framework is being scaled in and scaled up. According to reports, much of this has been made possible by Kurdish youth taking a lead role in building organization with an aim of constructing institutions that are autonomous from the state.

Some Responses on the International Left

Many across the ideological spectrum support the Rojava Revolution. This includes a range of notable individuals and organizations: Noam Chomsky, Michael Hardt, and Antonio Negri, and many more who are signatories to a statement urging people to donate to Rojava. David Graeber, David Harvey, and John Holloway are also in support.

Organizations pledging to provide and currently providing support range from Black Rose Anarchist Federation/Federación Anarquista Rosa Negra to the Marxist-Leninist Party of Germany (MLPD). A number of solidaristic organizations have sprung up across the world: from Australia, to England, to Brazil, and further on.

This is not to say support has come without criticism. In North America, Black Rose/Rosa Negra has, among other things, criticized what it sees as gender essentialism existing within the dominant feminist perspectives of the Rojava Revolution. Yet, Black Rose/Rosa Negra sees much that is positive in the Rojava Revolution and the overall Kurdish struggle, stating,

“the specific project of democratic confederalism (which is only one part of their political vision for 'democratic modernity' and the reorganization of society) has set the popular classes of Kurdistan in motion, constructing autonomous alternatives to capitalism, oppression and the state. In Rojava, and in some cases also in Bakur (north Kurdistan) when state repression doesn’t forbid it, workers’ cooperatives are being formed, land is being collectivized, women’s collectives are spreading, neighborhood assemblies are taking on power, restorative justice is replacing the court system, a democratic militia is defending the region, and other aspects of self-governance are being organized.”

As a result, Black Rose/Rosa Negra has publicly declared a set of organizational goals in relation to the Rojava Revolution. This includes, but is not limited to, organizing speaking tours, participating in the reconstruction of Kobanî, translating Kurdish texts, and pushing the U.S. government to remove the PKK from the list of terrorist organizations.

Other groups are and already have mobilized to support the Rojava Revolution. Rojava Solidarity NYC has consistently sent radical books and materials to Rojava. The Marxist-Leninist Party of Germany assists in providing direct support and manpower in the reconstruction of Kobanî. Many from around the world are assisting Kurdish military forces in the struggle against ISIS. This has come in the form of International Brigades.

This is not to say all on the left are pledging support for developments in Rojava. Some on the left express concern over what may be seen as a cult of personality around Abdullah Öcalan. The Anarchist Federation in the U.K., has largely admonished the Rojava Revolution. Workers Solidarity Alliance has also criticized the revolution from an anarcho-syndicalist perspective.

Most significantly though, Turkish anarchists–who have expressed solidarity with Rojava since its declaration of autonomy (coincidently, this declaration on July 19, 2012 came on the 76th anniversary of the beginning of the Spanish Revolution)—have also beyond mere statements. The Turkish Revolutionary Anarchist Action (DAF) prove direct auxiliary support to Rojava. (h

Moving Forward

While anarchists in Turkey have coordinated with those on the Kurdish left, the question remains as to whether the broader Turkish left will do so — if it has the capacity to do so. In March of 2015 there were a number of wildcat strikes in Turkey's auto industry, indicating some radical life within the Turkish working class. Will Turkey's labor movement show and act in solidarity with the Kurds and other ethnic and religious movements for post-state participatory self-governance and economic democracy? Or will the Kurds and other oppressed minorities remain alone in their fight for liberation? The answer to this question may prove integral to whether the Rojava Revolution will spread and move forward, or not.

*Alexander Kolokotronis is a BA/MA philosophy student at Queens College, City University of New York. He is the Student Coordinator of NYC Network of Worker Cooperatives, and the Founder of Student Organization for Democratic Alternatives.