Marxism and Art

In his most recent book, John Molyneux provides a well-researched overview and analysis of the visual arts in Western society, written from the standpoint of revolutionary Marxism. Molyneux was a longtime member of the UK Socialist Workers Party and is currently involved in Ireland’s People before Profit. He is a former lecturer in art history at the School of Art, Design, and Media at the University of Portsmouth, and is editor of the Irish Marxist Review.

In his most recent book, John Molyneux provides a well-researched overview and analysis of the visual arts in Western society, written from the standpoint of revolutionary Marxism. Molyneux was a longtime member of the UK Socialist Workers Party and is currently involved in Ireland’s People before Profit. He is a former lecturer in art history at the School of Art, Design, and Media at the University of Portsmouth, and is editor of the Irish Marxist Review.

This very knowledgeable writer has produced an enjoyable and useful history that covers many countries and periods, from Renaissance Italy and the Dutch Republic to contemporary Europe and America. Of particular interest is Molyneux’s definition of art as a distinct field of creative human labor: he considers it to be the opposite of work as it operates in class society, and particularly under capitalism, characterized as it is by alienation, commercialization, and commodification of the labor process, what is produced by it, and what happens to those products.

The book is aimed at people who are interested not only in art, but in the ways it is interwoven with politics, and it shows much about society and human interaction, both at work and more generally. The opening chapter, “What Is Art?,” explores the distinction between alienated and unalienated labor, and explains why art belongs to the latter category. Art, he argues, is “made by free, creative labor in a world dominated by the opposite … the general tendency of capitalism is to destroy all creativity in labor, not only in manual labor on production lines and in factories, but also in mental labor, in white-collar work” (3). Moreover, “art is work created by unalienated human labor and characterized by a fusion or unity of form and content. Furthermore, there is a connection between these two elements … Generally speaking, it requires unalienated labor to achieve such a fusion of form and content” (24).

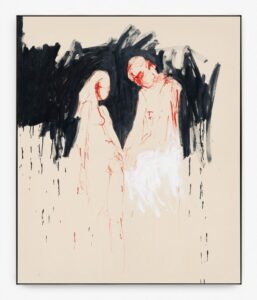

Molyneux examines in depth a range of artists and works of art, from Michelangelo’s David and The Dying Slave to Rembrandt’s The Jewish Bride, Picasso’s Guernica and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Jackson Pollock’s “drip” paintings, and a great many others. Throughout the book, he focuses not on the artists’ personal lives and creative predilections, but on “the nature of the labor they employed,” following Marx’s 1844 proclamation that “the entire so-called history of the world is nothing but the creation of man through human labor” (16).

In defining art, Molyneux is interested principally in the “capitalist or bourgeois era: that is, roughly from the beginning of the Renaissance (in Europe) through to the global present.” He expounds upon this point:

It is clear that something we would now call art has existed since at least the Upper Paleolithic period (that is, cave paintings, dating back over thirty-five thousand years) and that every human society or culture of which we have evidence was engaged in activities (painting walls, making music, dancing, storytelling, etc.) we would now be likely to call art. (10)

The author also emphasizes that labor is as deeply alienated today as it was in the past. Alienated labor, he reminds us, is an essential feature of capitalism because the accumulation of wealth on which the system depends cannot be effected without the separation of workers from autonomy over their lives and the extraction of their labor power by a system controlled by others.

In acknowledging the shortage of quality graphics in this book about visual art, the author provides a helpful direction:

This book is packed with references to specific works of art, particularly as examples illustrating historical and theoretical arguments. Ideally I would have liked similarly to pack the text with images of those works. Unfortunately this was not possible without inflation of the price of the book beyond what either I or the publishers consider acceptable. I would remind readers, therefore, that virtually every work referred to in this book is easily accessible online on any computer or smartphone. (xv)

The analysis develops through discussion of well-known artists; in addition to those mentioned above, he discusses Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Andy Warhol, Damien Hirst, and Tracey Emin (to whom he devotes a whole chapter). Molyneux also fully credits the many thinkers, artists, and activists who have influenced his work and his approach to art as employed here, including John Berger and his 1972 BBC TV series Ways of Seeing, which, along with its companion book, is among the most influential examinations of art ever. This work, and others by Berger, use oil paintings, drawings, and photographs to show how art reflects our society and history, and have forever changed how we view art.

Molyneux’s exploration of the work of Tracey Emin—a prominent artist in various media, including film, neon text, painting, drawing, photography, and sculpture— is a case study of how art can challenge its conventional definitions. He notes that Emin “is currently the most famous contemporary artist in Britain, and a woman. I don’t think this has ever happened before” (153). Even though Emin’s politics (Tory) are the opposite of the author’s, he defends her artistic efforts as important contributions that express changing social relations, especially those of “young working-class women and men” (168).

The final chapters of The Dialects of Art—“How Art Develops” and “The Dialectics of Modernism”—emphasize modern art in Europe and America and offer more insights to and evaluations of artists and their works, complementing Molyneux’s “lifelong engagement with art.” Among the strongest elements of the book is its emphasis on the historical and political foundations of many of the artists and the centrality of their work to contemporary art. Here, I must acknowledge that it will be impossible for me to look at any of the discussed paintings again without my view having been shaped and guided by Molyneux’s crucial insights. In particular, as Trotsky put it in Literature and Revolution:

the history of modern art is a history of rebellion from below followed by incorporation into the establishment . . . . Every new tendency in art has begun with rebellion. Bourgeois society showed its strength throughout long periods of history in the fact that, combining repression and encouragement, boycott, and flattery, it was able to control and assimilate every “rebel” movement in art and raise it to the level of official “recognition.”

The book’s concluding section discusses the “social turn,” or socially engaged art, of recent times, as well as the climate change crisis, which the author argues endangers the future of humanity and thereby the future of art itself (235). This danger is a long-term outgrowth of an economic system “owned and controlled by a tiny minority of the population” (236). Molyneux argues that human beings can and must change these oppressive conditions and realities:

Only in a society not based on the alienated labor of the majority will free artistic production become the property and practice of all. Until that is achieved, art will take its place in the quest and fight for human freedom, if not on the frontline—which will be occupied by the masses in struggle in the workplaces, the streets, and on the barricades—then as an important ally and essential supplier of spiritual nourishment as necessary in its way as boots and medicine. (237)

For those interested in social change and the importance of art as a challenge to the alienating core of capitalism, The Dialectics of Art is an excellent place to start.