Making Black Neighborhoods Matter

Lawrence Brown’s book The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America looks at the long history of intentional harm and damage done to Black communities caused by white supremacist practices, policies, and budgets. Brown uses redlined Black neighborhoods as his unit of analysis in order to understand the deep roots of urban apartheid but also to map strategies, approaches, and recommendations for structural change. While he charts the national scenario, he hones in on the city of Baltimore.

Lawrence Brown’s book The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America looks at the long history of intentional harm and damage done to Black communities caused by white supremacist practices, policies, and budgets. Brown uses redlined Black neighborhoods as his unit of analysis in order to understand the deep roots of urban apartheid but also to map strategies, approaches, and recommendations for structural change. While he charts the national scenario, he hones in on the city of Baltimore.

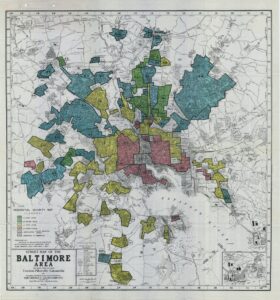

Brown is a holistic scholar utilizing history, the archives, quantitative and qualitative data sets from public health and urban planning, and police budgets. He brings these skill sets together in a masterful narrative well-written and highly accessible to organizers, undergraduates, and people who live and work in the neighborhoods of the Black Butterfly. Brown coined the phrase “Black Butterfly and the White L,” and it refers to the racialized geography of the city of Baltimore: the systemic disinvestment of Black neighborhoods in West and East Baltimore shaping a butterfly on the map and the White L of the white and gentrified areas, which enjoy and benefit from accumulated advantage. Graffiti artists like Nether and Chris Wilson painted a black butterfly. A hip-hop artist named Sun Zulu made a song titled, “The Black Butterfly,” where the Baltimore Center Stage had a butterfly series. As Brown described it, “It’s artists that really push the concept. Nether, he put on top of a building alongside the corridor of I-83 the ‘L’ and the ‘Butterfly’ in big white letters on this bright, brick building.” As Lawrence Brown stated, “You couldn’t miss it. Driving on I-83, I was just mind blown. That’s when I was like, okay, this is really going somewhere. People are taking it and running with it, and I was really excited by that.”

When I asked Brown how this project came out of his own political journey, he replied, “The roots began with the Black freedom struggles. The history I discuss in the book all began with the struggle to survive and the will to thrive and to try to make a way out of no way. The impetus for the book is really a sankofa which is a West African word for ‘looking back in order to move forward’ I’m looking back so I can then look at where we need to go.”

The book is organized as a playlist of sorts coming out of Brown’s love for funk music: Track 1: The Trump Card Track, Track 2: This is America, Track 3: The Negro Invasion, Track 4: Ongoing Historical Trauma, Track 5: Black Neighborhood Destruction, Track 6: Make Black Neighborhoods Matter, Track 7: Healing the Black Butterfly, and Track 8: Outro, Organize. The book is designed according to eight strategies needed to implement a robust racial equity approach and walk the reader through the steps of reflection, analysis, and actions needed to develop thriving Black neighborhoods. The outro is written for activists as they push for racial equity.

The historical and political economic context in Track 2: This is America places contemporary trauma tied to urban apartheid inside the history of slavery where Black people were auctioned off, purchased, sold, traded, rented, leased, and ripped out of their parent’s arms. Each moment of Black freedom is met with “whitelash” or white resistance to Black progress. The first whitelash was to the abolition of slavery and was followed by white supremacist violent massacres at the hands of former Confederates in 1866. Southern states passed Black codes to curtail Black freedom. He says, “White redemption was America’s violent reprisal of Black reconstruction.” (39)

The legal codification of white supremacist redemption resulted in the ratification of American apartheid. What was to come was deep racial segregation in education, transportation, propaganda in pulpits, and disseminated in newspapers, which fueled violence and dispossessions. No matter where Black people tried to escape the clutches of Jim and Jane Crow, they could not escape the violence visited by white supremacists.” (45) American apartheid was “white supremacist terrorism,” racial segregation in nearly all public spaces, land dispossession, exploitative labor arrangements including convict leasing and sharecropping, and racial cleansing or Black expulsions from sundown towns.

The second American whitelash was during the rise of Black power movements and their demands for freedom and economic justice, met with the U.S. government’s security apparatus known as COINTELPRO. This FBI program coordinated with local police to neutralize and kill Black leaders deemed revolutionary and framed as a “threat to national security.” The last or third American whitelash has to do with the violence following the election of President Barack Obama (2008) and the first Black Lives Matter uprisings (2014-2017). The rise of the Tea Party and the emboldened white supremacist groups re-born on the heels of Obama’s presidency led to the election of Donald Trump in 2016; “the champion of the Third American whitelash in both domestic and foreign policy” (58)

From this national scenario, he hones in on Baltimore where “no large metropolitan area can better illustrate the salience of structural violence better than Baltimore, which gave birth to urban spatial apartheid.” (63) Baltimore reveals the sophistication of structural violence deployed by city ordinances, real estate practices, mortgage lending, code enforcement, municipal budgets, zoning laws, urban planning, urban renewal, and urban development. Track 3: The Negro Invasion tracks urban apartheid, Baltimore style. This chapter charts the history of racial covenants and the fears of Black people moving into all-white neighborhoods.

As soon as the Negro appears, the white man moves away (63). A fabricated war against “negro invasion” consumed white Baltimore as Mayor James Preston became a national champion for government-enforced racial segregation. Public health measures became a way to justify Baltimore apartheid. From covenants to residential redlining to block busting to white supremacist violence, we get a brutal history of the architecture of systemic racism. This all evolved into “urban renewal” in the 1950s and white flight, which justified bulldozing down projects and running highways through Black communities. At the end of the chapter, Brown states, “America and its hypersegregated cities cannot move forward without acknowledging the fundamental aspects of the spatial war that characterized how Black people and communities would be treated according to the law” (103).

Track 4 looks at the ongoing historical trauma and utilizes Lakota scholar Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart for thinking about American apartheid as a form of historical trauma that results from damage inflicted on the affected entity, threatening health and viability. From the negro invasion to contemporary forms of “segrenomics” (Rooks, 2017) or the ways in which the private sector has profited from racial and economic segregation particularly within the school system. Brown argues that American apartheid and racial segregation operates through multiple and interlocking systems such as the criminal justice, finance, community development, real estate, housing, food, transportation, etc. The consequences are devastating; the flip side of concentrated poverty is concentrated wealth where the White L benefits from tax breaks, well-resourced schools, community centers, and even state of the art medical facilities. Track 5 subsequently tracks Black neighborhood destruction from root shock (or systematic shocks) to housing precarity to homicides and urban uprisings. Racism-based trauma led to the uprisings, which then expanded hyperpolicing and the expansion of the carceral state and thus more trauma.

This deep-seated historic and contemporary trauma sets the stage for Track 6, which outlines, why we must make Black neighborhoods matter. As Brown articulates, “Yeah, it all boils down to a simple ecological truth…which is really the thesis of my book. It’s that you cannot make Black lives matter without making black neighborhoods matter. That’s the public health challenge as well. You can’t make Black health matter when black neighborhoods are polluted, inflicted with toxic lead exposure that poisons the minds of Black babies, Black toddlers, Black infants.” As he describes it in the book, “Flowers in a garden need sunlight for proper growth and development.”

He lays out the beginning of a system-wide change by addressing 1) the ongoing historical trauma with a racial equity lens, equity does not mean equal; it means “corrective action (more resources need to be allocated to redlined areas because it takes more to equal the outcome)” (184); racial equity within schools, i.e., allocating $290 million more to Baltimore City Public Schools and $3 billion in capital to repair and rebuild infrastructure in redlined Black neighborhoods, suspending all public school closures in Black neighborhoods, and funding a community-driven process for culturally relevant and abolitionist curriculum in lieu of common core; 3) racial equity in community development, which includes centering racial equity in community development by passing a community reinvestment act and supporting Black-owned cooperatives; 4) racial equity in housing and ending homelessness by keeping people in their homes, providing foreclosure and eviction funds, reinvigorating public housing, building autonomous transitional housing, and implementing housing first; 5) racial equity in public health; 6) racial equity in public works e.g., public transportation; 7) racial equity in tax policy. At the conclusion of the chapter he states, “racial equity is not a vision or fantasy or utopia. It is a concrete process for creating and manifesting bright futures” (224).

In Track 7: How to Heal the Black Butterfly, Brown argues that we need a racial equity social impact bond of $3 billion to begin to bolster racial equity in Baltimore and to address pressing social issues from lead paint remediation to infrastructure for transit to infrastructure for social workers and counselors to funding the Baltimore Office of Equity and Civil Rights.

“Afrofuturistic ecological thinking is needed to imagine and envision thriving Black neighborhoods” (252). Afrofuturistic ecological thinking generates a scientifically seasoned faith, which allows practitioners to know that planting the seeds today will bring forth beautiful flowers (healthy people) in due season if nutrient rich soil (i.e., budgets, policies, and practices), abundant water (budgets and funding) and ample sunlight (accountability and participatory democracy) are put into place. We need to tend to these deep symbolic, psychological, structural wounds in order to heal.

Brown’s magnificent toolkit lays out a plan for how to radically restructure the systems, practices, and policies that have been put into place over the past 100 years stunting the growth and development of Black communities. In the last track, or the outro, he writes directly to organizers about confronting urban Democrats and the importance of organizing strategies to stop segrenomics and apartheid budgeting, hyperpolicing, and resource withdrawal. “Let a new America rise. Let a new America be born. Let every city and county engage in deep reflection and then implement the five steps of the racial equity process” (266). In order for this new America to rise, we all have to have body, soul, and intellect in the struggle for building a more equitable world. As Brown says, “Let’s all work to turn Baltimore into the Wakanda that it really is and should be.”

Resources

Brown’s toolkit for teaching the book with some digital archival material that educators can use.