Race, Capitalism, and Resistance in the United States

Introduction and My Experiences

“It is our duty to fight for our freedom. It is our duty to win. We must love and protect one another other. We have nothing to lose but our chains”.

You may recognize this as the rallying cry for the Black liberation movement in the United States, as written by Assata Shakur.

You may also recognize part of it from Marx: “Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains”.

I offer these two related quotes to prime our discussion of this new era in the struggle against racism and capital in the United States.

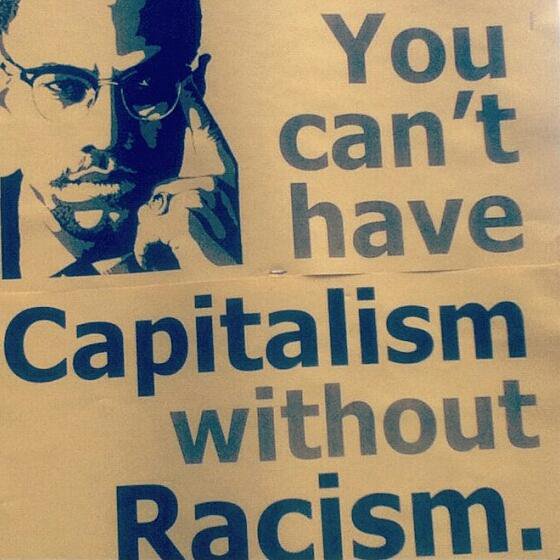

At this time, U.S. Black and Brown masses are experiencing even more systemic oppression and exploitation through over-policing, state violence, gentrification, lowered health and education outcomes, poverty wages and victimization through increased hate crimes to list a few concerns.

This struggle is also inextricably linked to the concerns of people of color in the current U.S. immigration crisis.

These assaults are occurring through detaining, deporting and criminalizing asylum seekers, kidnapping of border-crossing children and their parents, placing them in for-profit detention centers, the recent supreme court upholding the Muslim ban which limits travel for persons of 5 Muslim majority countries, ending temporary protection status for refugees from countries like Haiti, discharging enlisted immigrant military personal who were promised a path to U.S. citizenship through their service and threatening to de-naturalize U.S. citizens.

Only two weeks ago in San Diego, California, less than twenty miles from the Mexican-CA border, I joined with a coalition of Black and Brown activists and organizers to address the current U.S. immigration crisis. This coalition included African Americans, the Latinx community, Caribbean, African and Middle Eastern immigrant organizers and Palestinian liberation groups. This particular action drew thousands of activists from Oakland, San Francisco, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, San Diego, Arizona, New Mexico and the U.S. South.

Beyond the marching and activities of the day, we were able to educate each other, theorize and connect our individual projects of Black and Brown liberation, immigrant rights, fighting Islamophobia and renouncing U.S. imperialism abroad to our collective struggle against capital. If and when we can draw more masses from the current moments of outrage we are experiencing here, we will build bigger movements, harness collective power and be on our way create a new society.

My experiences in the types of activism described above have been relatively broad-based: In recent years I have participated in several actions, networked, protested, rallied, workshopped, created curriculum, and teach-ins with various Black and Brown-led movements across Southern California. In recent weeks this participation has intensified.

I also witnessed this collective organizing with Occupy ICE LA, a small group of activists who are camping outside the Federal Detention Building in Los Angeles demanding for the abolishment of the immigration detention empire. Most of the persons participating here in LA are Queer, working class, Brown and Black folks. There is also a significant Native American presence. Without the actions of the brave people in this movement throughout the U.S., their ability to mobilize across cities and their social media activism the call to abolish ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) would be unheard of; now abolishing ICE is becoming a liberal establishment campaigning point. Political opportunists might very well be bandwagoning on this hashtag but have yet to understand that the occupiers see their protests as a larger critique of U.S. imperialism and the Prison Industrial Complex as well as the very systems they uphold.

As with past movements, POC have been looking to uproot capitalism and develop their own theories of liberation, including those that can be found in non-Western epistemologies. The Native American presence at Occupy ICE LA in particular has contributed to this, similar to the way it was done at Standing Rock. In all of the groups I have described, praxis is informed by aspects of classical Marxism, traditional African epistemologies, Native American theories of collectivity and conflict resolution, as well as Black, Brown & Red liberation theories.

So what about identity politics and identity-first left movements?

I need to begin by admitting that I currently work with college graduate students in the oft-maligned “identity” course. Almost all universities in the United States have a diversity course requirement for all of their undergraduate and sometimes for graduate students. This course takes on many forms but generally addresses the oppression of minorities, issues of diversity, intersectionality, inclusion and so forth.

Sociologists Wright, Subedi and Daza note that these types of courses are often designated “low status” in general, and even more so when taught by people of color, queer folks and other minority groups… particularly when those instructors attempt to offer a Marxist analysis of the phenomena being explored. While educators of color do have opportunities to do research and pursue other passions, there is a great reliance on our ‘identities’ when it comes to representing for minorities in workshops. We are relied on to provide the necessary “cache” for the diversity courses that make universities compliant to their accreditation bodies and boards. These same scholars also note that in many ways, folks of color have become the face of this theoretical framing whose other unrelated work and authority is to be constantly challenged both in and out of the university.

For all of the neoliberal so-called commitment to identity, diversity, multiculturalism etc, in many ways the academy truly does not consider this to be important work, and it is in many ways merely performative. Why even mention the university? The heavy “reliance” on having people of color from social science fields teach these courses has created an interesting opportunity. While not every young college student will explore Marxism in a meaningful way, many if not most must take that problematic identity course.

Here I suggest that these courses, for all the ire they bring the left, have great revolutionary potential and that many of us who teach in this area take on this work with that understanding and ethos. For instance, what is generally referred to as classism in these courses amounts to elitism but with the proper framing, a conversation on classism can be used to explore the fundamental organization of society under capitalism.

Intersectionality theory is often used to understand the compounding consequences of different forms of oppressions. Exploring the intersections of race, gender, sexual orientation, ability etc as systems born out of the material relations shaped by capitalism can move the incompleteness of intersectionality theory to a place of radical criticality (Taylor, 2011).

Outside of the academy, the current Black and Brown liberation movements have been both disregarded and highly critiqued among the left. Some dismissals of these movements come from our popular progressive leaders. For example, during his 2016 presidential bid, Bernie Sanders initially refused to engage Black Lives Matter resulting in protesters disrupting his rally and demanding to be heard. I attended a local rally where Sanders collaborated with Black Lives Matter-LA to speak on criminal justice reform. Sanders said that up until recently he did not know that of the 2 million people incarcerated in the U.S., roughly ⅕ are in jail for “being poor” and was that he had only recently began to understand what the prison industrial complex meant for Black and Brown folks. He did however claim that he’s now aware and that he was quote “learning fast.” Most recently the same politician finally was able to proclaim, “Abolish ICE” after sustained pushback from activists. I mention Bernie Sanders here only as an example to demonstrate that dismantling any system and indeed uprooting capitalism remains a far-off cry for even the more progressive political class but those in these movements will continue to push their elected officials to take more radical stances.

We also find dismissals of Black and Brown organizations from some parts of the Marxist left who deconstruct every aspect of these movements, from theory, to organization, to practice, to revolutionary capacity. Often these organizations are accused of operating from a philosophical wilderness or taking an a la carte approach to Marxist thinking. This sociological waxing on might have potential but I rarely encounter critiques offered alongside a practical path to move us forward in conceptualizing alternatives to our current systems. I also never encounter these same critics at places where those of us are part of these movements do the theorizing, organizing and praxis.

Identity politics and intersectionality theory indeed have the capacity to be bourgeois. They can reduce struggles to individualized forms or reproduce the same alienated individual under capitalism. These concepts and elements of another stream, postmodern thought might offer theories of resistance without real liberatory models. It may be fair and even useful to critique some of these organizations for their political stances, and who they form alliances with or what we may consider reformist vs revolutionary action. I argue that many are in fact seeking emancipatory structures and are not in a mere state of resistance. The ways in which the leaders of the Black and Brown movements write, think, act and function will not look like those of revolutions past. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor very importantly reminds us that, “Marxism should not be conceived of as an unchanging dogma. It is a guide to social revolution and political action, and has been built upon by successive generations of Marxists”.

I also note that outside of academia, people of color, LGBTQ folk and indeed any vulnerable person who is driven to change his/her/their conditions in U.S. society can nevertheless encounter Marx. They can find Marx in spaces where people are taking action against oppression. Even where these organizations may not provide robust and constant theory, they offer humanizing spaces for masses to come together for the purpose of changing their material conditions.

Here I must agree with my friend and mentor Lilia Monzo who reminds us that, “While identity politics has been a thorn among many on the radical left due to its ties to a postmodern preoccupation with difference and multiple realities eliminate collective consciousness, …(she) believes we can draw on our multiple identities to create a broader base that challenges all forms of oppression. Organizing across differences has a humanist element that aligns well with the Marx’s new humanism that engenders mutual respect and equality”. (Monzo, 2018).

What then is the current role of the revolutionary Marxist left in these movements? And what does it mean to be in solidarity with such movements?

Founder of the Marxist-humanist tradition Raya Dunayevskaya understood the importance of Black liberation movements and those of other minorities noting that “The Black dimension is crucial to the total uprooting of the existing, exploitative, racist, sexist society and the creation of new, truly human foundations”.

From this understanding we should position ourselves in our organizations to do the theoretical labor that is required to be in critical solidarity with Black and Brown movements. As revolutionary Marxists, we view solidarity as sharing the risks of movements for the purpose of collective consciousness-raising and to create a new society. We also recognize our responsibility in proposing and theorizing “what comes next” when old systems have been overthrown. It should then follow that our critiques cannot be ones where we question everything and defend nothing. We should have the capacity to offer coherent theory and a measured response to the activities of these movements. Dunayevskaya in her brilliance also understood the contradictions produced in theorizing and organizing noting that, “Philosophy itself does not reach its full articulation until it has discovered the right organizational form” and “without a philosophy of revolution, activism spends itself in mere anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism, without ever revealing what it is for”. Our work here is to maintain this tension in what we offer as we witness how these movements both work out their theory and theorize their work.

One way to do so which is already occurring is for the Marxist Left to include People of Color in their gatherings, and vise-versa. A more important way is to understand the revolutionary capacity of the forms of expression we are seeing in current Black and Brown movements as our analysis is made. The discussion of non-western pedagogy and thought may produce anxieties for Marxists. Of Dunayevskaya Adrienne Rich writes, “she had the capacity, rare in people learned on Western philosophy and theory-including Marxists-to respect, learn from other kinds of thinking and other modes of expression: those of the third world or ordinary militant women, of working people who are perfectly aware that theirs in alienated labor and know how to say that without political indoctrination.”

Of the Combahee River Collective a group of Black women revolutionaries in the late 70s- African American studies scholar and Marxist Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor notes that the women, “not only saw themselves as “radicals” but also considered themselves socialists. They were not acting or writing against Marxism, but, in their own words, they looked to “extend” Marxist analysis to incorporate an understanding of the oppression of Black women.” In the same way, the activities of those in these movements have the same potential. This potential is actually what moves Marx from a mere theory of class struggle to one of real revolution and liberation.

As we press forward as the radical left, we eschew abstract universals while “recognizing” that particulars can orient us towards the future, i.e. that Marx’s dialectic (rooted in Hegel) offers space for the particulars of race, ethnicity and nationalities to be addressed. At this particular time, Black and Brown folks are on the frontlines of the struggle for liberation from the systematic oppressions of the day.

As conceptualized by Raya Dunayevskaya, “Blacks and other minorities, youth, women and the working class in fact form the powerful unified resistance to inspire a new society”. Those of us who participate in these current-day movements do not struggle in competition with the class struggle, we struggle together. We struggle for liberation which includes both the universal and the particular, a struggle to forge a new human society for the future, and to seize our freedoms in the present one.

Thank you.

Based on a talk at the panel on “Revitalizing Revolutionary Theory and Practice,” Loyola University July 13, 2018, sponsored by Loyola University and the International Marxist-Humanist Organization.

Originally posted at The International Marxist-Humanist.