The Protests in Lebanon Three Months After

In response to the failure of the state to manage and dispose of accumulated trash, a series of protests erupted in Lebanon in August 2015 demanding the toppling of the Lebanese corrupt regime and the basic rights for water, electricity and a clean healthy environment. This article provides an overview of the strategies used by the state to dismantle the protest movements, a class reading of the social movements three months into the protests, and an analysis of the strengths and achievements of the demonstrations.

The strategies of the state, its police and paramilitary branches in targeting activists and protest movements

The regime adopted multiple strategies to contain and dismantle the protests and shift public understanding of the protesters. These tools, visible in contingent interactions during the protests, in arrests conducted and in political statements, were all undeniably informed by the massive wave of NGO-ization of Lebanese security state institutions and apparatuses after the July war in 2006, and the rehabilitation, trainings, coordination and conferences on security and anti-terrorism issues organized for various Lebanese security sectors by foreign states. Various professionalized and ‘under the counter’ coercive and containment techniques have been adopted in these protests in Lebanon.

The classic trilogy: ‘Ghareeb, Ta’ati, Irhab’ (Foreigners, drugs & terrorism)

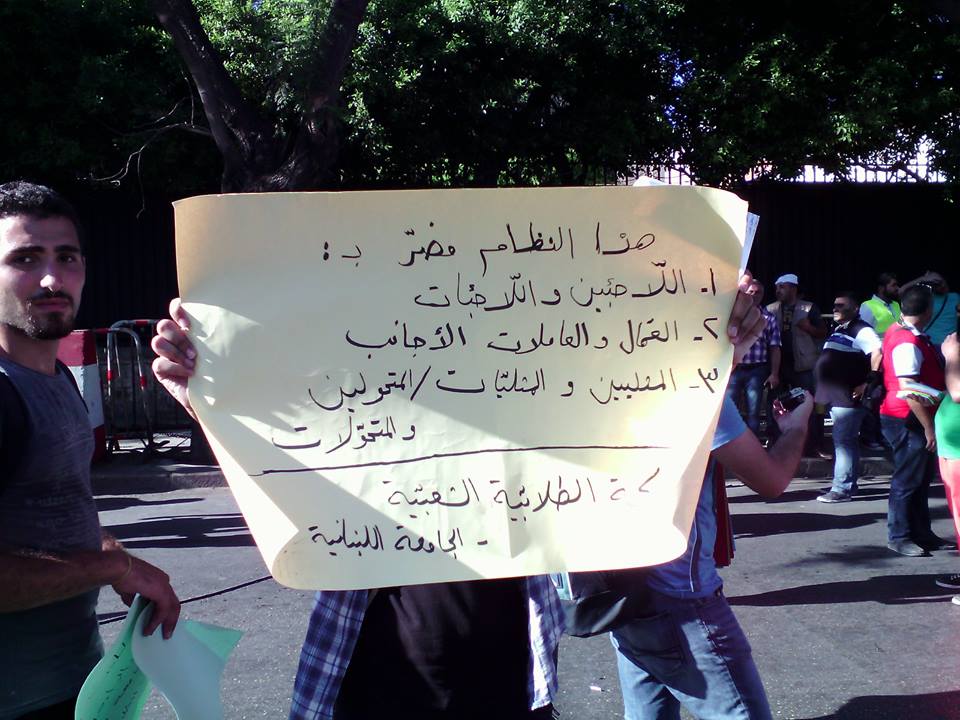

In his effort to discredit the legitimacy of the protests, Lebanese interior minister Nouhad El Machnouk relied on a classic trilogy that represented the protesters as drug addicts and non- Lebanese who are manipulating the protests for ulterior motives, like terrorism and implementing a foreign agenda. The irony of these accusations did not go unnoticed in a state that is literally and materially functional primarily because of foreign money and agendas. The interior ministry and its apparatus addressed the presence of moundasseen, or infiltrators, among the protesters, claiming that police have arrested Syrians and Sudanese nationals, as well as ‘drug addicts’ in the protests, while media sources hinted at the presence of ISIS enthusiasts planning terrorist attacks. These familiar categories are how the Lebanese regime understood and treated disobedience in times of social and political anxieties and violence.

The ideology of Al-Ghareeb, or the foreigner non-Lebanese, has been evoked to instigate fear, mistrust and recreate an insider/outsider binary. Al Ghareeb has always been highly racialized in the Lebanese discourse. Al Machnouk’s insistence on the Syrian and the Sudanese as the main infiltrators in the protests should not go unnoticed. Both racialized bodies are refugees and asylum seekers in Lebanon, and have been part of the Lebanese labor force. In recent years, with the influx of Syrian refugees into the country, the Lebanese state have used ‘the Syrians’ as a scapegoat category for almost every occurring problem, from lack of water, electricity, to the dearth of jobs. Sudanese asylum seekers have been engaging in a strike outside of UNHCR offices which they accuse of racism and discriminatory treatment, under severe conditions and bullying from both UNHCR and the police. Both black bodies — and we use black here inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates’s deconstruction of blackness in “Between the World and Me” (2015) as a category foremost implicated in the national dream of what it means to be Lebanese and the racialized ideology of the state vis-à-vis its residents– are highly managed and abused by the police and army. Both are not allowed to protest for their rights and are made to be invisible except when evoked as infiltrators. The use of the Syrian and Sudanese bodies works to evoke foreignness and terror, while justifying the excess of force and governance by the police.

Violence and the protests: military courts in a democratic state

Another strategy used by the interior ministry consists of portraying the protests as unsafe and violent, and protesters as irresponsible rioters, to extend its own “legitimate” use of violence in the protests. This was intensified by the coordination with paramilitary forces in the form of armed civilians kidnapping protesters and beating them up. In Akkar for example, armed civilians opened fire to dismantle a protest against the opening of garbage dumps, wounding five people.

More institutionalized and professionalized practices of detainment, such as the opening of temporary detention centers, were adopted, while less familiar maneuvering strategies were employed by riot police during protests, exhausting the protesters and depleting their spirit. However, police violence and detainment techniques seem to suddenly break away into “street violence” in other protests, with videos showing riot police throwing stones at protesters, following them in the street with tanks, and shooting disproportionate amounts of teargas directly at them, instead of into the air. One protester, Mohamad Kassir, suffered from full body paralysis when shot with a teargas canister from a point blank range on the night of the August 23rdprotest. Many other protesters have also been wounded. So far preliminary data show that approximately 250 people have been, arrested, 54 of them were referred to military court for trials. Among these were ten underage protesters. Al Machnouk have justified the excess of violence by claiming that the protesters have a desire to be beaten and arrested.

What is disquieting is the random arrests of protesters and activists convicted and tried in military, rather than civil, courts under the pretext of disturbing “civil peace,” attacking military hardware, and the barbed wire placed to prevent protesters from reaching the parliament and the government palace.

Three months of civil protests: a class reading of civil movements’ strategies, anxieties and of the abrupt fall of the momentum

The protests that engulfed Beirut were met with repressive measures by state security. which sparked and galvanized nationwide popular outrage. However, that revolutionary spark was gradually tamed by the sectarian-capitalist establishment and abandoned by the organizers of the street movement that became known as the Harak (mobility). In order to understand the current stalemate it’s noteworthy to point out how the so-called Harak is governed by middle-class anxieties and privileges that when threatened took on de-escalation tactics and deflated what could have turned into a historical event in the history of modern Lebanon.

Following the brutal attacks by state security against protesters there was a juncture when protests climaxed and became a force capable of creating a dent in the Lebanese political system. At that juncture the Lebanese political sectarian mafia felt intimidated by protesters who in their peaceful persistence turned into a raging fireball that awakened a portion of the dormant Lebanese consciousness. The peaceful method of the protests was a unique phenomenon in a Lebanon governed by daily organized violence. Thus, the dysfunctional Lebanese state that was being condemned on the street turned into a highly functional and efficient repressive machine orchestrated by minister of interior Nohad al-Mashnouk, funded trained and equipped by foreign aid programs.

By curbing the sentiment on the street from an uprising into a Harak, NGO-oriented activists proved that they were not fit to handle the fireball they had created; their organizational methods were inconsistent with the revolutionary spirit that united people in one protest. As pressure mounted on the streets people demanded a bigger scope of change; to topple the whole sectarian system. But protest organizers were reluctant to move towards such change and settled for merely protest organizing. Furthermore, the most prominent movements: We want Accountability, You-stink and other movements downsized their scope of action and gradually fell back from crude street defiance into flash mob activities and “event” organizers. While the street was fidgety and anxious for more action its energy was drained by the extensive meetings held behind closed doors by the You-stink and We want Accountability movements vying for the forefront of public representation. Nevertheless, the street at this point was still ahead of organizers’ hesitance; to the organizers the street increasingly became too big to handle and seemed like it might really get things out of their hands and shake the sectarian system from its foundations. As a result of not matching the sentiments on the street, the backpedalling started, which created time and space for politicians and state authority to organize their ranks and respond to the rebellion on the streets with calculated coercive and containment tactics. This is when campaigners began their withdrawal from an ongoing street battle to topple the regime, to a battle for recycling trash and finding solutions for the corrupted state whose own corruption led to the trash crisis.

On the 23rd of August was the protest that exposed the classist colours of the You-Stink organizers who betrayed the street calling on state security to clean the protest of agent provocateurs while thousands of protesters stood their ground defying state repression. Approximately two million refugees and migrant workers in Lebanon face the worst forms of daily violence; however the emphasis on the “Gharib” by minister of interior and rumors spread by organizers about “infiltrators” eliminated the participation or even the suggestion of including refugees and migrant workers in protests. The classist aspect amongst protest organizers especially among the You-Stink movement has a) criminalised and alienated protesters who have come from low income areas with vengeance and stood up to police brutality during protests and b) supplied Lebanese politicians a pretext to delegitimize the protest for being “infiltrated by agent provocateurs,” simultaneously blocking the way for participation of migrant workers and refugees and serving further bogiemanization of the latter.

While in privately planned minimalist-protests prominent You-Stink activists acted violently in front of the cameras as they confronted state security; these were celebrated as heroic acts, but when this same violence was taken by ordinary and low income angry protesters they were called “infiltrators” and “undisciplined elements” by You-Stink activists. Then it became clear that you-stink activists wanted any direct action to go through their filters and get their approval: a move to monopolize the public image and representation of the protests, not an unusual occurrence in sectarian Lebanese politics.

When violence was perpetrated by protesters in general as a defense mechanism against repressive state security measures, then the reaction by the whole array of the sectarian polity and their media trumpets was that of shock and bafflement, as if Lebanon was an island of tranquility. The fact that the state has been devolving in a dysfunctional mode for decades is in itself a form of daily violence that led to angry resentments on the streets this last summer. Violence against refugees, domestic migrant workers, LGBT individuals and women is an ongoing violence that doesn’t raise an iota of the outrage voiced against “violent protesters.”

The major achievement of the protests is that it has created cracks in the sectarian bubbles and some people have started leaking out to meet their counterparts andrealize that everything is in fact common, that they are all victims of the same repressive social order. The patriarchal sectarian blinders fell in the street. That’s why it’s imperative for the street movement to abandon the Harak mentality and return to the uprising mode. Only an uprising could impose a real threat to the capitalist ruling elite and the sectarian lords, while simultaneously creating confidence in the street to empower those undecided citizens still stuck inside their sectarian bubbles, who need to defect and leak out to the street. That’s why it’s erroneous to wait for a corrupt establishment to come up with solutions or even feel morally pressured by the Harak’s tactics and reform. The make-them-wait-promise-to-keep-them-waiting approach is what the Lebanese have had in the last 25 years; Mafioso politicians will only feel intimidated if their own thievery was directly threatened and when their own timid constituencies find an alternative to their hegemonic sectarian social order.

And so the street movement has sunk into a frustrated feeling of defeat as a result of the Harak’s inaction and de-escalation tactics. The biggest mistake was committed while the climax on the street was at its peak; the organizers who led the protests failed to embrace and organize those outraged on the streets who had just abandoned their sectarian social bubbles. Those dissident individuals who dared to defect from the social hegemony of family authority and broke away from the sectarian political identity that governs their social relations needed a safe Haven.

The Harak’s weakest point is the fact that on an organizational level its ranks are dominated by middle-class activists steeped in an NGO mentality, and as a result the revolutionary mood on the street was taken hostage by their middle-class anxieties. Seeing that the street swelled with angry protesters making demands beyond the scope of action that was planned by the organizers of You-Stink, the Harak then de-escalated its measures of direct action. Worse, the campaigners switched their modus operandi into exclusive and elitist-looking attempts, seeking media stunts rather than taking the uprising to the next level, thereby nipping in the bud the revolutionary character of the protests. The toxic elitist sentiment lies within decision-making circles that kept on meeting behind closed doors away from the street and missed the chance of establishing an open sit-in at Riad al-Solh that could function as a shelter, a place of belonging, a visible ongoing body of the protest and a safe haven reclaiming public space. Secular activists who have had experience with and a history of street protests and organization have failed to open the doors of the streets or/and secure them – to embrace first-time protesters who flowed onto the streets since August 22. Many young individuals who had just abandoned their traditional habitats at the risk of severing their familial/social-sectarian ties joined their peers in the streets denouncing the defeatism of their parents’ generation. They needed an alternative to embrace them, but that alternative did not match their needs.

It’s precisely this type of middle-class anxieties that reproduce the system within the protest movement itself. The two major movements that were born out of public resentments against trash and corruption, You-Stink and We want Accountability, became the two most dominant movements in the Harak. It increasingly seems that the way in which these two movements operate and politically differentiate themselves from the other have placed them at the risk of slipping into a polarization that resembles the political mode of March 8 and March 14 political blocs, the political alliances that were formed following the withdrawal of Syrian security from Lebanon in 2005.

At present, autumn’s arrival has cooled down the atmosphere in Beirut. The sentiment in the street seems to be back to square one, but not without its symbolic achievements. The backtracking from movements’ organizers into tactical gambling to solve the trash crisis deflated the revolutionary enthusiasm that created a momentary existential threat to the Lebanese political order. Middle-class activists who are at the risk of missing a historical chance to change the lethal Lebanese political equation ought to realize that it’s only a matter of time until their middle-class privileges that they cling to are eventually going to vanish by the political establishment they hesitated to topple.

The shaking of the patriarchal discourse and political cynicism: reconfiguring hope & political action

Perhaps the undeniable strength of the protests so far rests in their ability to put an end to the cynicism and helplessness reigning over conversations and actions for change in Lebanon, thereby producing political hope in the ability to dismantle the Lebanese corrupt structure. The personal-emotive transformations experienced by activists and non-activists alike, and the possibility of imagining something new, have created a stimulating platform for political and social debates. One slogan held in the protests “A revolution on the life we live with (the help of) drugs and pills,” portrays this personal revolution over slow and structural death in a stagnant system.

A revolution over the life we live with drugs and pills (Source: Al Manshour)

The protests have also caused a crack in the discourse and esthetics of power itself. This is visible in the state’s rhetoric and arguments against corruption that are no more convincing. Ministers and state leaders are ridiculed and mocked in the protests. Intellectuals are challenged publically and accused of being paternalistic.

In a counter move, the regime attempted once again to attack the authenticity of the protests on the basis of morals, manners and the esthetics of protesting. They filed lawsuits against name defamation, arrested activists under the pretext of disrespecting the flag and nation. Not everything of course has been challenged. The sacredness of certain political leaders and parties, notably Hezbollah, remained mostly unchallenged and undebatable while protesters try to advance the idea of “All means All,” that everyone is corrupt and needs to be held accountable.

However, social movements have yet to offer new forms of political action and expression. Many of the protests have been incorporated into sometimes outdated and a politically insignificant way of doing politics & protesting. Protests have been turned into a media spectacle, constricted by recycled speeches and old political music that has lost the ability to express the present. A rise in nationalism is also noticeable, where many times there is an intentional forgetting of Palestinians, Syrians and foreign migrant workers and maids who also have crucial demands and rights in the country they reside in and are as affected by the same system if not more severely.

The feminist bloc, a feminist platform for groups and activists that emerged as a result of the protest to provide feminist solidarity and secure a safe space in the protests for women and gender-minority groups to express their opinions and demands, has been marching in the protests under the slogan of “the patriarchal regime kills.” This is a good example of these practices of challenging and revealing what lies inside the Lebanese discourse of power. The bloc’s chant “I want to dance, I want to sing and I want to topple the system” can be read as a double commentary on the freedom of women to occupy the streets, but also as challenging hegemonic male-centered ways of doing politics and protesting, signaling the need to challenge and take back the streets and protests re-appropriated by “the Lebanese male activist” and recycled activist forms of political expressions.