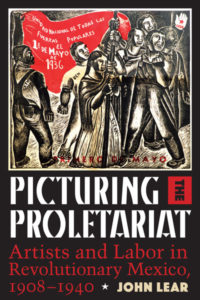

Picturing the Revolutionary Mexican Working Class

Picturing the Proletariat: Artists and Labor in Revolutionary Mexico, 1908-1940.

Picturing the Proletariat: Artists and Labor in Revolutionary Mexico, 1908-1940.

John Lear

Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017, vii + 366 pp

$29.95 paperback

Any mention of Mexican art immediately brings to mind the high cultural achievements of two civilizations separated by long centuries. There are the artifacts and constructions of the indigenous peoples, the art of the Aztecs and Mayas that predate the Spanish Conquest. And in our own time, the spectacular murals that are the icons of contemporary Mexico – particularly the celebrated works of the so-called los tres grandes, Diego Rivera, Jose’ Orozco and David Siqueiros. But if it is the muralists who captured and continue to claim attention and admiration worldwide, there were other types of artistic expression in twentieth century Mexico, less celebrated if no less vital and essential to the advancement of a radical social movement.

By the turn of the twentieth century, economic development under the dictatorship of Porforio Diaz had bred an industrial proletariat, an aggrieved peasantry, and an expanded middle class all grown increasingly restless and disaffected under the extended years of his rule. The revolt of 1910 against his regime launched a decades-long social and political revolution that inspired a generation of Mexican artists and illustrators and finally saw the emergence of a national culture of Mexicanidad – a blend of radical ideology and a new-found nationalism. John Lear presents the graphic results of the commingling of art and revolution, the works of artists that displayed, expressed, and encouraged the radical and revolutionary impulses of the Mexican working class and campesinos at the same time that the artists themselves, largely of middleclass origins, formed themselves into collectives and became increasingly drawn into the front ranks of the popular movement for social change. Lehr notes the contributions of artists like Luis Arenal, Pablo O’Higgins, Leopoldo Mendez, and a score of others relatively unknown in North America.

The Mexican Revolution gathered momentum in the same years that war and revolt convulsed Europe, disturbing traditional sensibilities and provoking new and unique styles in the graphic arts – dadaism, expressionism, surrealism…all of these left their imprint on the work of Mexico’s’ artistic community in the early twentieth century, even as they illustrated social injustice and celebrated the power of collective action. But unlike developments in the totalitarian states – the reactionary “socialist realism” enforced by Stalin in the Soviet Union, with its twin counterpart in Nazi iconography – the blend of art and politics in Mexico never conformed to any “official” regulation, despite governmental subsidy of so many artistic projects and the artists who produced them. In their work on public displays and in the journals and posters of the Mexican labor movement, Mexican artists and illustrators maintained a general independence of style and expression, ranging from cartoon-like graphics to photo-montage to surreal depictions of social conflict and class solidarity.

The ascension of Lazaro Cardenas to the presidency in the mid-1930s proved to be the high tide of Mexico’s social revolution. Cardenas took the side of the popular movements and his administration began a program of land reform, extension of labor rights ,the encouragement of cooperatives and finally the expropriation of the foreign owners of Mexico’s oil industry. At the same time the Mexican Communist Party, following directives from Moscow, initiated a Popular Front policy of cooperation with liberal and progressive elements in anti-fascist alliance. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War further raised the political temperature. A reaction typical of Mexican leftists was Arenal’s drawing for the cover of the union periodical Futuro featuring an armed worker-soldier with the caption Mexico no sera’ Espana! (Mexico will not be Spain!) – a warning to right-wing elements.

At the same time that he carried through policies of social reform, President Cardenas also reorganized and strengthened Mexico’s ruling political party, containing labor and peasant organizations within a corporatist system that would endure under his more conservative successors until the end of the century. Lehr takes note, but does not dwell on the various rivalries and quarrels both within and among Mexico’s labor unions and political organizations, Communist, radical and moderate. The dissident leftist Diego Rivera was expelled from the Mexican Communist Party and became an intimate associate of Leon Trotsky after the Bolshevik leader went into Mexican exile. Trotsky was later assassinated in Mexico City by an agent of Stalin’s secret police. Both Luis Arenal and David Siquerios had personally participated in previous failed attempts on Trotsky’s life.

Lear’s presents this work along with a plethora of reproductions, plates and photographs of the art rendered in labor publications, union journals and public walls, illustrations that carry his narrative as well as the written text. His is a unique study of popular culture in a society undergoing radical renovation.