“The Reddest Reddest Red Sun in Our Heart, Chairman Mao”

(Women xinzhong zuihong zuihongde hong taiyang Mao zhuxi he women xin lianxin)

This is the first part of a four-part article. The other parts can be found here:

Socialist revolution in the third world countries depends on the existence or nonexistence in the population of a sizable element capable of playing the role assigned to the proletariat in classical Marxian theory—an element with essentially proletarian attitudes and values even though it may not be the product of a specifically proletarian experience. The history of the last few decades suggests that the most likely way for such a “substitute proletariat” to arise is through prolonged revolutionary warfare involving masses of people. Here men and women of various classes and strata are brought together under conditions contrasting sharply with their normal ways of life. They learn the value, indeed the necessity for survival, of discipline, organization, solidarity, cooperation, struggle. Culturally, politically, and even technologically they are raised to a new and higher level. They are, in a word, molded into a revolutionary force which has enormous significance not only for the overthrow of the old system but also for the building of the new.

— Paul Sweezy and Charles Bettelheim[1]

The great actions of the hero … are the expression of his motive power, lofty and cleansing, relying on no precedent. His force is like that of a powerful wind arising from a deep gorge, like the irresistible sexual drive for one’s lover, a force that will not stop, that cannot be stopped. All obstacles dissolve before him.”

— Mao Zedong, 1918[2]

The east is red, the sun is rising

China has brought forth Mao Zedong.

He seeks the people’s welfare.

He is the people’s great savior.”

— “The East is Red” lyrics [3]

As U.S.-China rivalry has intensified in recent years many Western Leftists have been confused and divided over how to respond. To date, discussion has mostly centered on whether China is still socialist or has become just another capitalist imperialist superpower in its own right. On the one hand, Maoists like the editors of Monthly Review and the Qiao Collective[4] ardently defend the former view and insist that the Left should support China against U.S. imperialism.[5] On the other, many around New Politics, Tempest, Spectre, Solidarity, and the Fourth International argue that China is capitalist or state capitalist, but either way this rivalry is just inter-imperialist competition and the left should, like Lenin vis-a-vis WWI, side with neither Beijing nor Washington. Looming behind the issue of imperialism is the question of the nature of Mao’s revolution and the social system his party installed. After all, if the left doesn’t have a clear understanding of the nature of the Chinese political economy, how can it take a position on China vis-a-vis the U.S.? Yet as Kevin Lin, Brian Hioe, and Dan La Botz have pointed out, the Maoist and neo-Maoist “anti-imperialist” Left[6] is perversely resistant to examining or even discussing China. Lin writes that “I’ve continually encountered a refusal to seriously discuss China…. Whenever I’ve tried to initiate these discussions, there are people who try to shut it down because they would say they don’t want to criticize China for fear of giving ammunition to the right wing in the U.S…. So that does make it difficult to advance the discussion on China and the U.S.-China rivalry within the U.S. left if the largest political group [the DSA] simply refuses to engage on this question.”[7] Political, theoretical and historical ignorance, though much in vogue these days on the right, is hardly the best basis for the left to develop a robust Marxist socialist position on China. The following essay aims to open up this discussion by interrogating the socialist credentials of the Chinese Communist Party through a re-examination of Maoist theory, the historical rise of Mao Zedong in the 1930s and 40s, and the system he installed in 1949.

I. THE CHINESE ENIGMA

How is the left to understand China today? How did a communist party that was once overwhelmingly comprised of proletarians (60% workers in 1926) and in the mid-1920s led the largest workers’ and peasants’ revolt in history, end up installing a Stalinist totalitarian police state?

Who would have imagined in 1949 that Mao Zedong, who based his entire revolution on the peasantry, would nine years later impose a stunningly brutal forced collectivization that worked and starved to death more than 30 million of the very peasants who powered his party to victory in 1949?

Who would have imagined that Deng Xiaoping — dedicated communist from the age of 17, proletarian pipe-fitter at Le Creusot Iron and Steel Plant near Paris, France in the 1920s, revolutionary veteran of the Long March, political commissar of the Red Army whose victory vanquished imperialism, landlordism, and capitalism in China — would as his penultimate testament, invite Western capitalists to exploit China’s police-state-enforced union-free, OSHA-free, EPA-free ultra-cheap labor, and then follow this up with his final testament, the massacre of hundreds if not thousands of students protesting in Tiananmen Square against the corruption that his marriage of capitalism and Stalinism wrought in China?

Or again, who would have imagined that Xi Jinping, son of Xi Zhongxun, political commissar and founder of the Shaanxi-Gansu Soviet base Area (Mao’s home base in the 1930s-40s) who was renowned for his moderate policies and use of non-military means to pacify Tibetans and Xinjiang Uyghurs, then lauded again in 1979 when as governor of Guangdong province he initiated economic liberalization, opening up Shenzhen, the first of China’s Special Economic Zones that powered China’s industrial rise, would reject his father’s easy-going approach to install militarized terror and torture police states in Tibet and Xinjiang, turn the whole country into an Orwellian surveillance state to monitor its 1.4 billion citizens 24/7 to control every moment of their waking lives, crush another student-led democracy movement in Hong Kong and suppress the private sector, expropriating and locking up many of the same Chinese capitalists who led China’s economic miracle?

But there you have it. Such contradictions have bedeviled western China scholars and Maoist leftists since the first days of the revolution. In 2018, after a visit to Xinjiang where he observed first-hand how the combination of crude Maoist concentration camp brainwashing (on which see below part VII) and Xiist digital totalitarianism are deployed to crush the Uyghurs and erase their culture, leftist University of Sydney professor David Brophy wrote in Jacobin magazine, “How did a revolutionary state, which came to power promising to end all forms of national discrimination, end up resorting to such horrific policies?”[8] Good question.

II. THE MAOIST MYTH OF CHINESE SOCIALISM

My approach rejects the orthodox theoretical framework and historical narrative that has shaped discourse about the nature of the Chinese revolution since the 1970s and is taken for granted by Maoist politicos and most China scholars regardless of their attitudes to Mao and the communists — namely that Mao’s revolution installed a socialism of sorts, and Deng Xiaoping “overthrew socialism and restored capitalism” such that China is more or less capitalist today. In Maoist theory there is no necessary connection between the proletariat and socialism and therefore no need for institutions of working class democratic self-rule so long as the “substitute proletariat,” the Communist Party, upholds the “correct line” — “proletarian politics.” Thus despite the fact that the working class played no role in Mao’s revolution or in the post-revolutionary dispensation, China was nevertheless socialist under Mao, they claim, because his revolution abolished capitalism and private property, nationalized the economy, replaced the market with central planning, liberated women, introduced the “iron rice bowl” job guarantees, cradle-to-grave state-provided social services including free medical care, free schooling, childcare and other welfare benefits. By contrast, Deng Xiaoping and his successors abandoned Mao’s “correct line,” re-introduced the market, broke the “iron rice bowl” job guarantees, privatized housing, medical care, schooling beyond middle school; invited foreign capitalists to exploit Chinese workers and promoted the development of domestic capitalists.

As a Marxist, this Maoist just-so story never made sense to me. In my experience the ideological framework of Maoism has posed an insuperable barrier to understanding the nature of the Chinese revolution and the regime it installed. First, it fails to grasp the theoretical originality and non-Marxist character of Mao’s party-substitutionist “new class” revolution. Second, Maoist theory has no capacity to explain the historical contradictions of the system Mao installed because if China was socialist then its horrors must be explained as aberrations, inexplicable in relation to Mao’s Thought. Thirdly belief in this theory has obliged Maoist China scholars and ideologues to defend (or ignore) indefensible, even criminal practices by the Chinese regime that are blindingly contrary to any common-sense definition of socialism. Fourthly, Maoist theory equally fails to explain why, if Deng Xiaoping and his market reformer successors were “restoring capitalism,” have they systematically subverted their own market reforms precisely to prevent the wholesale restoration of capitalism?[9] In short, the Maoist theoretical framework is not just useless, it’s led scholars and left ideologues to produce empirically untenable analyses, write shelves full of nonsensical books, and proffer morally indefensible apologetics for China that, like an earlier generation of Western apologists for Stalin’s crimes, have only further discredited the very idea of socialism.

How did Maoism come to dominate Western discourse and China studies despite its manifest contradictions and inadequacies? At least four reasons come to mind. Start with the fact that Marxism never had deep roots in China. Marxism was an import. China’s commercial and industrial proletariat in the early 20th century was miniscule, though learning fast, and China had no tradition of Social Democracy or revolutionary socialist politics. Early 20th century radicals were more attracted to anarchism than Marxism because Marx’ focus on the industrial working class seemed irrelevant in the Chinese context. Indeed, the founders of the Communist Party in 1921 were inspired by the Bolshevik revolution but most had little if any knowledge of Marxism when they founded the Party. They converted to communism before they had read Marx and most never became Marxists at all. They became Stalinists and Maoists or were driven out of the Party in the late 1920s and 30s.

Secondly, China’s totalitarian police state has been far more effective in completely crushing dissent and erasing virtually all historical memory of non-Maoist currents, the Tiananmen uprisings, the Charter ’08 movement, and so on, than Soviet and East European Stalinist rulers. Mao and his henchmen like Kang Sheng murdered hundreds of Chinese Trotskyists during the 1930s and 40s, and in 1952 locked up the last thousand or so of them for decades, extinguishing the last active alternative socialist political pole of attraction beyond Maoism. There was never space in China for dissidents, samizdat, or a Marxist underground such as the Workers Defense Committee KOR that developed in Poland from 1976 to promote worker self-organization and politicize their movement which ultimately gave rise to the Solidarnósc trade union in 1981.[10] China’s own would-be Marxist theoreticians, socialist labor organizers, and socialist revolutionaries such as 1970s-era Trotskyists and democracy activists Chen Erjin, Wang Xizhe, Wei Jingsheng, Tiananmen and Charter ‘08 democracy advocates including Liu Xiaobo, have all been ruthlessly crushed, murdered, locked away in prisons or labor camps for decades, driven into exile, and forgotten in China.[11] Today, Xi Jinping talks up Marxism all the time. But when Beijing University students took him seriously and initiated study groups to read Marx, they were arrested and disappeared.[12] As a result, since the 1940s all legitimate political discourse in China has been constrained within the Maoist framework.

Thirdly, there has been nothing in China studies to compare with the debate around the “new class” theories of Russia and the East European Stalinist regimes advanced by Bruno Rizzi, Milovan Djilas, Michael Voslensky, Maria Hirszowicz, Max Schachtman, Hal Draper, and others.[13] Since the 1970s, Marxist mode of production theory has been fruitfully developed to explain the transition (or failed transitions) from pre-capitalist to capitalist societies and to explain the ongoing dynamics of contemporary capitalist economies. But in western China studies, Maoism still rules.

Fourthly, and closely related to the last point, as Fabio Lanza recently recounts in his history of the Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, the left wing of U.S. China studies was founded by a cohort of young anti-war, Cultural Revolution-infatuated graduate students and young professors in the 1960s and 70s who idealized China and Vietnam in response to U.S. imperialism in Southeast Asia.[14] I would add that they were liberal anti-imperialists, not Marxists. They learned their “Marxism” from Mao who learned his mostly from Stalin. They learned Chinese but could not visit China until after Mao and Nixon broke the ice in 1972. And when they did go in the seventies, as “friends of China” with pre-arranged itineraries and minders to keep them from speaking with ordinary citizens, most bought the Cultural Revolution Potemkin village scenes of “equality,” “mass line politics,” and so on without reservation. As Orville Schell recalls in Lanza’s book, “We were in love with China.” Some didn’t buy it. But most did because they were romantic third worldists who worshiped the Red Sun. As Maoist professors, they have misled generations of students with a delusional ahistorical fabulist vision of China.[15]

The net result of the foregoing is that, aside from important Trotskyist interpretations by Livio Maitan and Au-Loong Yu, and state capitalist expositions by Ygael Gluckstein and Nigel Harris, there are no other “new class” theorizations of China either in China or the West.[16] This essay and the book it’s drawn from aim to partially fill that gap by presenting a bureaucratic collectivist theorization of Mao’s party-substitutionist revolution, the system he installed, and the contradictions and historical tendencies of that system.

My argument in brief

This essay will explain why the contradictions and atrocities noted above cannot be understood as aberrations from socialism but are instead built into, rational, and indispensable to ruling class reproduction in China’s system. Mao’s revolution was the world’s first successful communist party-led peasant-based national liberation revolution and his example and writings provided the model and theory for the entire wave of third world revolutions from the end of WWII through the 1970s. But the strategy of socialism from above, led by self-styled omniscient “savior dictators” like Mao, was doomed from the start in China and everywhere else. Pace Paul Sweezy, for all their years of guerilla-war “plain living and hard struggle” nowhere did a single substitute proletariat install any kind of workers’ government, any kind of socialist government, or even any kind of democracy. In every case they installed “new class” societies of one kind or another, some worse than others. In Yugoslavia, China, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia they installed Stalinist bureaucratic-collectivist class societies modeled on Stalin’s USSR. In Algeria, Mozambique, Angola, Zimbabwe, and Guinea Bissau they installed one-party (or even one-man) dictatorships and capitalist or state-capitalist regimes. In Cuba, although Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and their comrades weren’t fully Stalinists to begin with, after the imposition of the US blockade they turned to the USSR for support and soon adopted all the trappings of a one-party Stalinist state.

In China, the prototypical case, I will explain how over the course of Mao’s revolution, the petty bourgeois intelligentsia substitute proletariat developed its own “new-class” interests which were nationalist, bureaucratic, autocratic, anti-democratic, and anti-socialist. While Mao’s strategy of a communist party-led peasant revolution succeeded in overthrowing the old order, his vision of top-down socialism was doomed to fail because the overriding priority of the new national chauvinist ruling class was to “catch up and overtake the West” by means of forced-march self-industrialization, and this could only be financed by decades of coercive surplus extraction from China’s workers and peasants which in turn could only be enforced by a dictatorship that crushed worker struggles for trade unions and all struggles for democracy.

Thus my response to Professor Brophy’s question is that when Mao’s revolution is understood for what it really was — a revolution of, by and for the Stalinist “new-class” party-army-bureaucracy that seized power and installed a totalitarian police state and bureaucratic collectivist economy, then the apparent contradictions of the system vanish.

Let’s start with what socialism is not:

Nationalized property isn’t necessarily socialist. It all depends on who owns the state. In China from Mao to now, society owns and controls exactly nothing. All land and natural resources are owned by the state. Under Mao the economy was entirely owned and run by the state and the state was and is the exclusive property of the collective party-bureaucratic ruling class, a dictatorship beholden to no one. Since Deng’s market reforms, private capitalists have been reintroduced but they exist only at the pleasure of the CCP, as Xi Jinping has recently reminded them.

Economic planning isn’t necessarily socialist. It all depends. Planning by whom, for whom? In Mao’s China, as in Stalin’s Russia, the economy was planned from the top down by the party-bureaucracy for the interests of the party-bureaucracy while China’s workers, peasants, intellectuals and everyone else were shut out of decision-making about politics, the economy and everything else in China. Since Deng’s “market reform and opening,” central planning has been reduced but by no means abolished. State central planning still overwhelmingly rules China’s economy.

“Iron rice bowl” job guarantees weren’t necessarily socialist either. Under Mao, workers had the “right” to a state job not because China was socialist but because Mao sought to maximize economic growth by maximizing labor inputs so he needed all hands on deck. In fact they had no right not to work. Similarly, the Party liberated women to join the workforce but never helped them secure equality with men. Under Mao, the state provided industrial workers with jobs, housing, schooling, medical care, and modest retirement benefits because without a market there was no other way for people to access such services. But while the state dispensed those services, the workers lived their entire lives in conditions of unfreedom.

Nationalization, economic planning, job guarantees, state-provided schooling and healthcare would all be important components of a socialist economy and society but those are hardly sufficient. The key factor is missing: workers’ democracy, mass popular democracy. Without democracy there can be no socialism (and without socialism there can be no real democracy).

Conversely, Deng Xiaoping did not ditch socialism since there was no socialism to ditch. He threw open the economy to Western investment creating Special Economic Zones to exploit Chinese labor, broke up the rural communes to let peasants farm on their own account, broke the industrial workers’ iron rice bowl job guarantees, privatized schools, medical care, social services, and housing to discipline labor and open it up to deeper exploitation. But he never fully restored capitalism, never restored private property, never privatized significant state-owned industries. Instead, he and his successors introduced measured capitalism to rescue the CCP when Europe’s communists were collapsing, but contained it “as a bird in a cage” as a useful adjunct to the planned economy.[17]

III. THE SOCIALISM OF SAVIOR-DICTATORS

I contend that Mao Zedong was first and foremost an ethno-nationalist in the tradition of the “self-strengtheners” of 19th and early 20th century China. From Sun Yat-sen to Mao, Deng and Xi Jinping, China’s leaders have all been obsessed with one overarching goal: to overcome China’s “century of humiliation,” achieve “wealth and power,” “catch up with and overtake the US” in order to reclaim what they have imagined is China’s deserved pride of place as the premier civilization and culture of world history because, in Sun Yat’sen’s words, Chinese “are the finest and most intelligent people in the world,” thus the natural leader of humankind and, in Xi Jinping’s words, the rightful successor to “the declining West.”[18]

Yet Mao wasn’t just a Han nationalist like Sun Yat-sen. He was also a socialist. But he was not a Marxist. Aside from its versatile vocabulary, he had little use for Marxism with its focus on the industrial proletariat. Mao was, rather, a latter-day pre-Marxian utopian “socialism-from-above” kind of socialist. Mao’s socialism drew not from the working class, democratic, self-emancipation “socialism from below” ideas of Marx and Engels exemplified by the Paris Commune and the Russian Soviets, but from the pre-Marxian “socialism-from-above” ideas of the 18th and 19th century utopian socialists, anarchists, and agrarian populists.[19]

This was the socialism of self-appointed elites, self-styled “smart guys” convinced that they alone possessed the “correct ideas”: the necessary vision and strategy to create and run a socialist society, thus they should rule as beneficent dictators dispensing socialism to the benighted masses. Such would-be savior-dictators included the Babouvistes who wanted to set up a temporary albeit well-intentioned “educational dictatorship” over and above the people, abolish private property, and construct a society of “absolute economic equality.” And Joseph Proudhon who imagined himself a beneficent “manager-in-chief” ruling a society where trade unions, universal suffrage, constitutions and the like, were all banned (“All this democracy disgusts me” he said). And the fraudulent “anti-authoritarian” Mikhail Bakunin for whom the realm of “absolute freedom” was to be found in absolute conformity to Bakunin’s own “invisible dictatorship” — virtually the model for Mao’s own ultra-authoritarian “anti-bureaucratic” “Cultural Revolution.”[20] And the Russian agrarian populist Alexander Herzen and the Narodniks who claimed that “the advantages of backwardness” could enable agrarian nations to “skip over historical stages” and that “pure” peasants were harbingers of human redemption, a force that could lead Russia to an idyllic rural socialism bypassing the horrors of Western capitalism. Lenin fiercely criticized Herzen’s idealism and voluntarism but Mao appropriated Herzen’s idealist thesis as the basis for his doctrine of socialist construction by means of mind over matter, “red over expert,” the power of human will, etc. in the Great Leap Forward.[21] Mao was an intellectual descendent of utopian socialists, anarchists, and agrarian populists like these.

How, then, did the Chinese Communist Party, founded with the help of the Bolsheviks, born in the cauldron of workers’ strikes and uprisings in the industrial and commercial cities of Canton (Guangdong) and Shanghai in early 1920s, end up under the leadership of a pre-Marxian utopian socialist? An interesting question, which the rest of this essay will endeavor to explain.

[continued in part 2]

Notes

[1] On The Transition to Socialism (Monthly Review Press, 1971), 52-53.

[2] Maurice Meisner, Mao Zedong (Cambridge: Polity, 2007), 1-9, 12.

[3] The East is Red, c. 1930s.

[4] For the purposes of this paper I group these all under the rubric of “Maoists” because even though some don’t defend Mao or the Cultural Revolution they still maintain that China today is somehow socialist, non-capitalist, or at least more progressive than Western capitalism, and they uphold the Maoist theory of party-substitutionism and look to substitutionist leaders like Mao, Ho Chi-minh, Fidel Castro and so on to lead the socialist revolution instead of socialism from below, workers self-emancipation, and socialist democracy.

[5] Monthly Review “New Cold War” issue; Qiao Collective, “Socialism with Chinese characteristics,” undated. Cf. Brian Hioe, “Manichaeism with Chinese characteristics: a look back on the ‘China and the Left’ conference,” New Bloom, September 30, 2021.

[6] This paper is narrowly focused on the Chinese case. But the critique I present here of the theory of party substitutionist-led third world revolutions as summarized by Paul Sweezy in the epigraph above, applies generally to all the Maoist-inspired substutionist revolutions from North Korea and Vietnam to Africa and Latin America. See my “Cuba and the end of third worldism?,” Tempest, August 6, 2021.

[7] “China and the U.S. Left,” Spectre, July 17, 2021; Brian Hioe, “The Qiao Collective and left diaspora Chinese nationalism,” New Bloom, June 22, 2020; Dan La Botz, “Internationalism, Anti-Imperialism, and the origins of campism,” New Politics (Winter 2022), 64-74.

[8] “China’s Uyghur repression,” Jacobin, May 31, 2018.

[9] On this topic see my “The Chinese road to capitalism,” New Left Review 1/199 (May-June 1993), 55-99; and “Why China isn’t capitalist (despite the pink Ferraris),” Spectre, August 17, 2020.

[10] Jan Jósef Lipski, KOR: A History of the Workers’ Defense Committee in Poland, 1976-1981 (Berkeley: University of California, 1985).

[11] Louisa Lim, The People’s Republic of Amnesia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[12] Brian Williams, “Chinese government arrests Marxist Society for union organizing,” The Militant, October 29, 2018.

[13] Bruno Rizzi, The Bureaucratization of the World (New York: Free Press, 1939); Milovan Djilas, The New Class (New York: Praeger, 1957); Max Schachtman, The Bureaucratic Revolution (New York: Donald Press, 1962); Michael Voslensky, Nomenklatura: Anatomy of the Soviet Ruling Class (London: Bodley Head, 1984).

[14] Fabio Lanza, The End of Concern (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 104; Kin-ming Liu (ed.), My First Trip to China (Hong Kong: Musemag, 2012).

[15] Lanza, Concern, 114-15.

[16] Ygael Gluckstein, Mao’s China (London: Allen and Unwin, 1957); Livio Maitan, Party, Army and Masses in China (London: Verso, 1969); Nigel Harris, The Mandate of Heaven (London: Quartet, 1978); Au Loong Yu, China’s Rise: Strength and Fragility (Pontypool: Merlin, 2012).

[17] “Why China isn’t capitalist,” op cit.

[18] Sun Yat-sen, San Min Chu I: The Three Principles of the People (New York: Putnam, 1922), chapter 1. For a current and comprehensive exposition of this ethno-nationalist thesis see Liu Mingfu, The China Dream (New York: CN Times Books, 2015). Xi Jinping borrowed this moniker for his own signature China Dream project.

[19] On this distinction, see Hal Draper’s Two Souls of Socialism (Berkeley: Bookmarks,1966), pp. 10-16. On anarchist influences on Mao, see Arif Dirlik, Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 160-61, 195 and 294-97; and his The Origins of Chinese Communism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 178-70. Also: Robert A. Scalapino, “The evolution of a young revolutionary – Mao Zedong in 1919-1921,” Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 42, No. 1 (November 1982), 29-61. On populist influences on Mao and his teacher Li Ta-chao, see Maurice Meisner, Li Ta-Chao and the Origins of Chinese Marxism (Cambridge: Harvard, 1967), 262-66.

[20] On Bakunin’s phony anti-authoritarianism, see besides Draper, Aileen Kelly’s reply to David T. Wieck, “Freedom and anarchy,” New York Review of Books, April 1, 1976. On Mao’s phony anti-authoritarian authoritarianism, see my “Mao and self-limiting ‘Cultural Revolution,’” Against the Current, Vol. 1, No. 3 (Spring 1992), richardanthonysmith.org/articles.

[21] On Herzen’s influence on Mao, see Maurice Meisner, Mao Zedong (Cambridge UK: Polity Press 2007), pp. 19-20. Lenin’s critique is to be found in “Democracy and Narodism in China,” July 15, 1912, Collected Works, vol. 18.

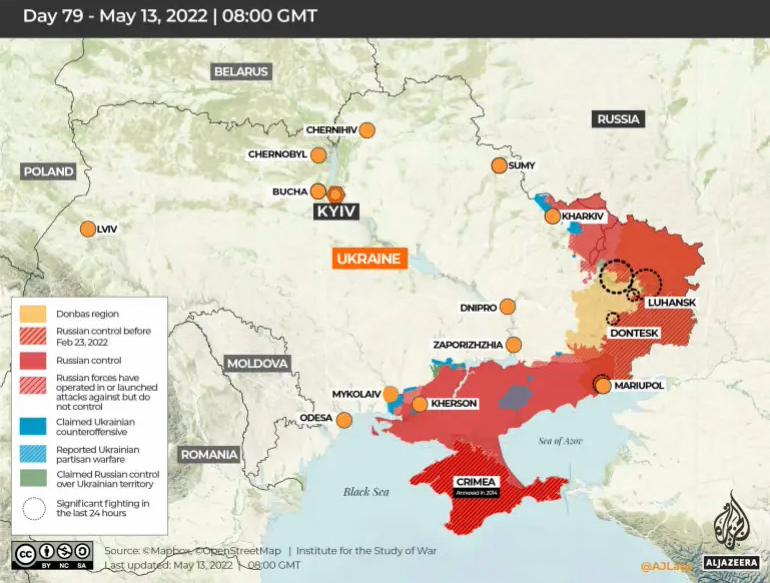

The Russian invasion of Ukraine caught most observers by surprise. I, for one, didn’t think that the Russian government would be so foolish as to invade. If Ukraine resisted, the Russian military could destroy it with nuclear weapons but couldn’t conquer it with the conventional forces they had deployed to its borders. The Russian ruling class needed a deal, not a war. Ukraine in the European Union and out of NATO, like Finland or Sweden, would have suited it very well. The Russian people certainly didn’t want war.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine caught most observers by surprise. I, for one, didn’t think that the Russian government would be so foolish as to invade. If Ukraine resisted, the Russian military could destroy it with nuclear weapons but couldn’t conquer it with the conventional forces they had deployed to its borders. The Russian ruling class needed a deal, not a war. Ukraine in the European Union and out of NATO, like Finland or Sweden, would have suited it very well. The Russian people certainly didn’t want war.

“The Russian invasion of Ukraine has no justification, but NATO…” It is difficult to describe the emotions I and other Ukrainian socialists feel about this “but” in the statements and articles of many Western leftists. Unfortunately, it is often followed by attempts to present the Russian invasion as a defensive reaction to the “aggressive expansion of NATO” and thus to shift much of the responsibility for the invasion to the West.

“The Russian invasion of Ukraine has no justification, but NATO…” It is difficult to describe the emotions I and other Ukrainian socialists feel about this “but” in the statements and articles of many Western leftists. Unfortunately, it is often followed by attempts to present the Russian invasion as a defensive reaction to the “aggressive expansion of NATO” and thus to shift much of the responsibility for the invasion to the West.

As Ukraine continues to resist Russia’s horrific aggression and attempt to conquer and annex the south and east of the country, the quantity of arms being supplied to Ukraine by the United States and other western countries has steadily increased. As the country and people suffering from this naked imperialist aggression, the Ukrainians have every right to receive weapons from whoever wants to send them, regardless of the aims of those countries doing so, or the extraordinary hypocrisy of these imperialist powers.

As Ukraine continues to resist Russia’s horrific aggression and attempt to conquer and annex the south and east of the country, the quantity of arms being supplied to Ukraine by the United States and other western countries has steadily increased. As the country and people suffering from this naked imperialist aggression, the Ukrainians have every right to receive weapons from whoever wants to send them, regardless of the aims of those countries doing so, or the extraordinary hypocrisy of these imperialist powers.

On May 5 and 6, 2022, a two-day international conference of the European Solidarity Network with Ukraine with the support of the NGO “

On May 5 and 6, 2022, a two-day international conference of the European Solidarity Network with Ukraine with the support of the NGO “

I have not (yet) been raped. Unlike most women my age (not quite 50), unlike nearly every adult woman I know, I have never experienced unwanted sexual touch from a man.

I have not (yet) been raped. Unlike most women my age (not quite 50), unlike nearly every adult woman I know, I have never experienced unwanted sexual touch from a man.

Shortly after I arrived at UC Berkeley as a freshman in 1966, I learned about and was entirely won over to the idea(l)s of “socialism from below.” Still I was unsure of what these political ideas meant for my life choices – until I met the newly-burgeoning women’s liberation movement. I felt and saw the shackles of sexism’s permeation of capitalism, how this had shaped my being. Unpacking how the “personal is political” illuminated and articulated so much of my lived-experience as a woman who had qualities dismissed as “unfeminine” and definitely not sexy. My life as a political activist was decided.

Shortly after I arrived at UC Berkeley as a freshman in 1966, I learned about and was entirely won over to the idea(l)s of “socialism from below.” Still I was unsure of what these political ideas meant for my life choices – until I met the newly-burgeoning women’s liberation movement. I felt and saw the shackles of sexism’s permeation of capitalism, how this had shaped my being. Unpacking how the “personal is political” illuminated and articulated so much of my lived-experience as a woman who had qualities dismissed as “unfeminine” and definitely not sexy. My life as a political activist was decided.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has been met with strange responses on the part of segments of the USA Left and among many progressives. While, generally speaking, there has been a strong condemnation of the Russian invasion, there has simultaneously been a

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has been met with strange responses on the part of segments of the USA Left and among many progressives. While, generally speaking, there has been a strong condemnation of the Russian invasion, there has simultaneously been a

“I define solidarity in terms of mutuality, accountability, and the recognition of common interests as the basis for relationships among diverse communities. Rather than assuming an enforced commonality of oppression, the practice of solidarity foregrounds communities of people who have chosen to work and fight together. Diversity and difference are central values here—to be acknowledged and respected, not erased in the building of alliances. Jodi Dean (1996) develops a notion of ‘reflective solidarity’ that I find particularly useful. She argues that reflective solidarity is crafted by an interaction involving three persons: ‘I ask you to stand by me over and against a third.’ This involves thematizing the third voice ‘to reconstruct solidarity as an inclusive ideal,’ rather than as an ‘us vs. them’ notion. Dean’s notion of a communicative, in-process understanding of the ‘we’ is useful, given that solidarity is always an achievement, the result of active struggle to construct the universal on the basis of particulars/differences. It is the praxis-oriented, active political struggle embodied in this notion of solidarity that is important to my thinking—and the reason I prefer to focus attention on solidarity rather than on the concept of ‘sisterhood.’”

“I define solidarity in terms of mutuality, accountability, and the recognition of common interests as the basis for relationships among diverse communities. Rather than assuming an enforced commonality of oppression, the practice of solidarity foregrounds communities of people who have chosen to work and fight together. Diversity and difference are central values here—to be acknowledged and respected, not erased in the building of alliances. Jodi Dean (1996) develops a notion of ‘reflective solidarity’ that I find particularly useful. She argues that reflective solidarity is crafted by an interaction involving three persons: ‘I ask you to stand by me over and against a third.’ This involves thematizing the third voice ‘to reconstruct solidarity as an inclusive ideal,’ rather than as an ‘us vs. them’ notion. Dean’s notion of a communicative, in-process understanding of the ‘we’ is useful, given that solidarity is always an achievement, the result of active struggle to construct the universal on the basis of particulars/differences. It is the praxis-oriented, active political struggle embodied in this notion of solidarity that is important to my thinking—and the reason I prefer to focus attention on solidarity rather than on the concept of ‘sisterhood.’”

[Editors’ note: The

[Editors’ note: The

The Ukrainians are fighting a just war against an imperialist invasion and they therefore deserve to be supported. Their right to self-determination is not only relevant against Russia. It is also relevant to their decision to fight. They alone should decide whether to carry on fighting or accept whatever compromise is put on the table. They don’t have a right to involve others directly in their national defense though: no right to get NATO powers to impose a no-fly zone over their country or to send them weapons and equipment that could widen the war’s scope. They deserve to be supported, but it is only a moral obligation.

The Ukrainians are fighting a just war against an imperialist invasion and they therefore deserve to be supported. Their right to self-determination is not only relevant against Russia. It is also relevant to their decision to fight. They alone should decide whether to carry on fighting or accept whatever compromise is put on the table. They don’t have a right to involve others directly in their national defense though: no right to get NATO powers to impose a no-fly zone over their country or to send them weapons and equipment that could widen the war’s scope. They deserve to be supported, but it is only a moral obligation.

The terrible images reaching us after the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Kyiv region reveal the scope of the Russian offensive. These images force political leaders to unanimously condemn Putin’s attack on Ukraine, including Putin’s natural allies (the far-right). In this context, some of the most radical among us feel the need to express -if only through an aesthetic gesture- their aversion to national unanimity. For example, Members of Parliament (MPs) from the CUP (Catalan pro-independence radical left) and the BNG (Galician nationalist left) as well as the Secretary General of the PCE (Communist Party)

The terrible images reaching us after the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Kyiv region reveal the scope of the Russian offensive. These images force political leaders to unanimously condemn Putin’s attack on Ukraine, including Putin’s natural allies (the far-right). In this context, some of the most radical among us feel the need to express -if only through an aesthetic gesture- their aversion to national unanimity. For example, Members of Parliament (MPs) from the CUP (Catalan pro-independence radical left) and the BNG (Galician nationalist left) as well as the Secretary General of the PCE (Communist Party)

[Note: This article was originally submitted to Jacobin in the hope of initiating a debate among the radical left. It was rejected.]

[Note: This article was originally submitted to Jacobin in the hope of initiating a debate among the radical left. It was rejected.]

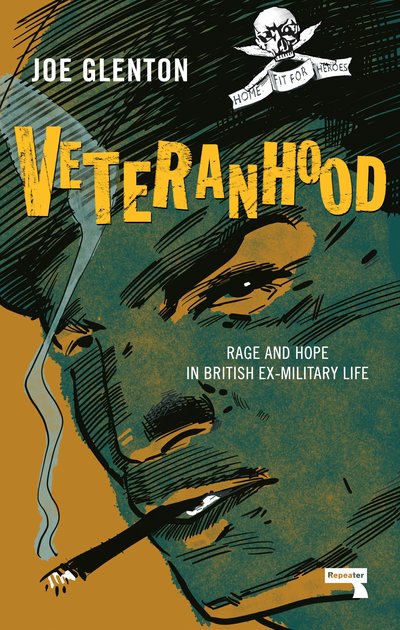

Military service in the U.S. and the U.K. promised more than it ever delivered for many post-9/11 volunteers. As sociologist and Vietnam vet Jerry Lembcke observes, “This generation of veterans went off to Iraq and Afghanistan with more hoopla than any generation since World War II. But a lot of them, particularly the men, came back deflated and disappointed with the experience they had. It did not live up to the mythology of what war is supposed to be, because there is no glory in these inglorious wars.”

Military service in the U.S. and the U.K. promised more than it ever delivered for many post-9/11 volunteers. As sociologist and Vietnam vet Jerry Lembcke observes, “This generation of veterans went off to Iraq and Afghanistan with more hoopla than any generation since World War II. But a lot of them, particularly the men, came back deflated and disappointed with the experience they had. It did not live up to the mythology of what war is supposed to be, because there is no glory in these inglorious wars.”

On April 8,

On April 8,

Rosario Ibarra de Piedra, one of the most important figures of the Mexican left, died on April 16, 2022 at her home in Monterrey, Nuevo Leon at the age of 95. She was the leader of the Mexican human rights group Eureka Committee of the Disappeared and was the first woman candidate for the Mexican presidency in 1982 as the candidate of the Revolutionary Workers Party (PRT). She ran a second time in 1988. In 2006, thanks to proportional representation, she was elected to the Mexican Senate where she served first as the PRT Senator and then as Labor Party (PT) Senator.

Rosario Ibarra de Piedra, one of the most important figures of the Mexican left, died on April 16, 2022 at her home in Monterrey, Nuevo Leon at the age of 95. She was the leader of the Mexican human rights group Eureka Committee of the Disappeared and was the first woman candidate for the Mexican presidency in 1982 as the candidate of the Revolutionary Workers Party (PRT). She ran a second time in 1988. In 2006, thanks to proportional representation, she was elected to the Mexican Senate where she served first as the PRT Senator and then as Labor Party (PT) Senator.