A New Politics in America – Part 3 – the New Right of the 1980s

This is the third part of A New Politics in America. Part 1 looked at the Civil Rights movement and the White Backlash; Part 2 examined the impact of the economic crisis of the 1970s; Part 3 discusses the decline in American power, and then turns back to look at how all three elements contributed to the growth of a New Right from the 1960s to the 1980s.

The United States: A Declining World Power

While the United States remained a world power—and the greatest military power on earth after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991—U.S. military might did not necessarily always lead to military victory and modern weapons could not always ensure its place as the leading world power.

True, the United States easily defeated Iraq in Operation Desert Storm during the Gulf War of 1990-1991, but few in government noticed that America was walking through a mine field. In the next decade there were no such easy victories.

Wars tended to become quagmires, swamps and quicksand—swamp metaphors that oddly enough worked well to describe the desert wars that sucked both significant numbers of fighters and enormous amounts of money and military hardware into a vortex of permanent insurgency and civil or religious war. The IED—the "improvised explosive device" made by amateurs out of industrial junk—turned out to be capable of defeating the most sophisticated army and of sending hundreds of soldiers home with amputations, cranial trauma, and often-permanent brain damage. The United States attempted to impose order on an expanded Middle East that came to stretch from Tunisia to Afghanistan and Pakistan, but the territory proved to be covered with landmines both literally and figuratively.

The American government apparently easily overpowered Afghanistan in 2001—but fourteen years later the war continued with no end in sight. Similarly, the Iraq War of 2003 saw President George W. Bush declare victory in his shipboard “mission accomplished” speech, but the war soon turned into a disaster of enormous proportions, taking hundreds of thousands of lives, costing billions of dollars, virtually destroying the nation of Iraq. The War in Iraq still goes on today, now as a fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), a vast geographic and intense ideological struggle that eludes resolution. Americans understandably have found the goals, methods, and developments of these wars incomprehensible, since neither the government nor the media had any clear explanation of their purpose or their objectives beyond stopping what Bush called “the bad guys.”

The War on Terrorism, launched by Bush and continued by Obama, guided by no clear moral, ideological, or strategic goals, became a shifting, shiftless, and murderous affair. The more conservative among the American people, however, attributed the defeats in those imperial wars not to the Republican George W. Bush who had launched them, but to the Black, Democratic Party president, who some believed was a Muslim who had not been born in the United States. Many white Americans, especially the men among them, men who had lost their high paying jobs and their former role as patriarch, now also saw their country in what seemed like permanent defeat.

Defeated on the battlefield, the United States was also being defeated it seemed to many in the world marketplace. Without a political labor movement, neoliberal globalization—global investment, production, and trade—became institutionalized in trade agreement and international organizations. President Bill Clinton negotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, a treaty that in essence formalized the economic integration of Canada, Mexico, and the United States that had been taking place. The banks and corporations of all three countries could now exploit the natural resources and the workers of the entire continent. U.S. unions demanded some protections, but the “labor side agreements” provided little enforcement of labor rights violations in any country. Many in the unions and in the working class came to believe that NAFTA had been the principal source of job loss and low wages in America.

Similarly the Clinton government supported the admission of China to the World Trade Organization—and though Longshoremen, Teamsters other unions and environmentalists carried out militant demonstrations against it at the Battle of Seattle—China was admitted in 1999. China’s economic growth averaging over 10 percent a year between 1992 and 2008 made it the second largest capitalist economy in the world and a rival to both the United States and the European Union. Many in the American working class—who found that virtually everything they purchased in big box stores like Walmart had been made in China—now believed that Mexico and China represented their chief competitors and that the United States had to change its trade policies.

While it was Bill Clinton who had negotiated NAFTA and supported admission of China to the WTO, it was George W. Bush who had granted “permanent normal trading relations” to China. And President Obama put the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a NAFTA-like agreement with 11 countries on four continents, at the top of his agenda for 2016, calling it a “made in America” agreement. Both major parties, it seemed to many workers, were unwilling to protect them from the movement of jobs abroad. Sections of the American ruling class of bankers and financiers, their political allies and ideologues also became concerned that the United States was losing the ability to dominate global developments. The decline of American power and the need either to reassert it or to transition to some new international order became a central concern among both conservative and liberal leaders, among both Republicans and Democrats.

The New Right of the 1980s

As during the 1970s the prosperity of the post-war period ended, social conflict increased, and America suffered defeat in Southeast Asia, the white middle classes—that is the small business people and the better paid layers of the working class—most of them living in the suburbs, found solace in a variety of places: in the Evangelical churches, in the right-to-life movement, in the National Rifle Association, and in the Republican Party. These organizations and a constellation other conservative religious and civic groups, often financed by wealthy rightwing foundations, constructed a “New Right” that in the 1980s and found a political home in the Republican Party, where Christian fundamentalists and right-to-life activists generally happily cohabited with the Chamber of Commerce, the National Manufacturers Association, and the anti-union Right-to-Work organizations of the economic conservatives.

Basing their thinking on the culturally profound America belief in individualism inherited from Protestant forbearers, John Locke, and the authors of the U.S. Constitution, a wide variety of rightwing preachers, journalists, and intellectuals constructed a new ideology founded on the Christian religion, traditional family values, the American dream of homeownership, a conservative conception of community embodied in the segregated suburb, the right to bear arms to defend one’s home and family, the economic importance of small business, and a belief in America’s role as the indispensible nation. Conservative Evangelical ministers like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson and Christian commentators like Paul Weyrich became the leaders of the New Right, though other sorts of conservatism were growing too.

Also living in the Republicans big house—for white people—were the Neocons, that is the neoconservatives—some are former anti-Stalinist leftists, others students of Professor Leo Strauss of the University of Chicago, yet others followers of American Ambassador Jeanne Kirkpatrick, or writers and readers of Commentary and The Weekly Standard. The Neocons included such figures as Elliot Abrams, John Bolton, Paul Bremer, Richard Perle, and Paul Wolfowitz, a small crowd of highbrow intellectuals, politicians, and activist bureaucrats who had learned their skills directing cloak-and-dagger skullduggery and the military intervention of the murderous wars against the poor and the left in Central America.[i]

The Neocons advocated an aggressive foreign policy internationally to reassert what they called American leadership in the world, but what might be more accurately described as a return to American imperialism of the Golden Years. Remarkably their Weltanschauung formed at places like the University of Chicago largely coincided with the views of many of the Evangelicals and NRA members, and with the outlook of many white middle class and working class victims of industrial collapse and conversion: all looked back to the good old days and forward to the coming sunrise of American power and prosperity. “Let America be America Again,” one might say.[ii]

Another important ideological strand that also began to develop within the Republican Party, growing stronger in the 1990s and into the twenty-first century was libertarianism. The roots of libertarianism might be found in John Locke’s political and economic theory, some call him the “father of libertarianism,” though, of course, Republicans and Democrats also often trace their roots back to Locke whose ideas formed the basis of American constitutionalism and capitalism. It was the Russian-American novelist Ayn Rand, however, who popularized laissez-faire capitalism in her novels The Fountainhead (1943) and her popular Atlas Shrugged (1957), and who inspired many of the first American libertarians.

A secular rationalist, Rand’s ideals appealed to those on the right who were not attracted to the moralism of Evangelical Christianity. Libertarians adopted classical economic views, arguing that government should be kept to a minimum, allowing citizens to do as they liked, not only in the marketplace but also in society. So, like other conservatives, libertarians opposed government regulations and government social programs, but different than others also took a hands-off position on questions of abortion and gay rights, which they considered matters of personal liberty. Some libertarians even criticized corporations on the grounds that they were government creations, while others opposed military conscription as an imposition on individual liberty.

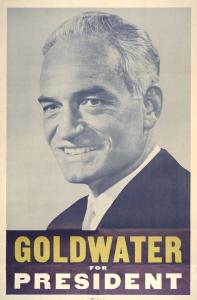

Libertarianism developed as a political force in the Republican Party several years later out of the presidential campaign of Republican Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater in 1964. Goldwater was, as Gary Wills argued in a recent article, the founder of the “hard right” that we see today in candidates like Ted Cruz. Goldwater’s book The Conscience of a Conservative (1960), became what Patrick Buchanan called the “New Testament” of conservatives of the time. Wills summarizes Goldwater’s remarkably rightwing agenda:

Goldwater called for the elimination of Social Security, federal aid to schools, federal welfare and farm programs, and the union shop. He claimed the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board decision was unconstitutional, so not the ‘law of the land.’ He said we must bypass and defund the UN and improve tactical nuclear weapons for frequent use.[iii]

E.J. Dionne Jr., the Washington Post columnist, argues in his Why the Right Went Wrong: Conservatism—from Goldwater to the Tea Party and Beyond, that all of the basic elements of the future Tea Party movement could be found in Goldwater’s Conscience of a Conservative. But it would take decades more of economic crises and political conflicts before those ideas became politically viable and before a constituency for them to grow out of the wreckage of the industrial economy, out of white racial resentment, and out of the sense of insecurity created by the country’s decline both domestically and on the world stage.

All of these conservative currents became increasingly attractive to Americans, especially to the white middle and working classes who had been threatened by the civil rights and women’s movements and battered by the economic upheavals of the 1970s and early 1980s. Between the economic crises of the 1970s and the age of War on Terror in the 2000s, many former union members and Democrats, independents, and Republicans moved into this world of conservative organizations and ideologies. Today then, it is not surprising that “Republicans hold a 49%-40% lead over the Democrats in leaned party identifications among whites. The GOP’s advantage widens to 21 points among white men who have not completed college (54%-33%) and white southerners (55%-34%).”[iv]

[i] Greg Grandin, Empire’s Workshop: Latin America, the United States, and the Rise of the New Imperialism (New York: Holt, 2007), passim.

[ii] As Langston Hughes pointed out in his poem titled “Let America Be America Again,” that America was never his.

[iii] Gary Wills, “The Triumph of the Hard Right," New York Review of Books, Feb. 11, 2016, p. 4.