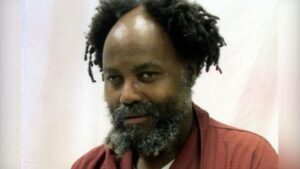

Mumia Time or Sweeney Time

New Politics editor’s note: Already suffering from liver disease and hepatitis C, the incarcerated journalist and former Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal has tested positive for COVID-19 and has congestive heart disease. Supporters are calling for Abu-Jamal and other medically vulnerable prisoners to be immediately released and allowed to recover in freedom (Free Mumia, War Resisters League, Democracy Now!). We post from the New Politics archives a 2000 article on Abu-Jamal by labor historian Dave Roediger. Proposing an anti-racist direction for the U.S. labor movement, Roediger highlighted instances of labor solidarity with the Free Mumia movement, including a 1999 shut down of 30 ports, and Abu-Jamal’s solidarity with labor including a refusal to cross a television network technicians’ picket line. Abu-Jamal was taken off death row in 2011 but continues to serve a life sentence without parole following a 1982 trial widely denounced by human rights groups as unfair and racially charged.

IN FEBRUARY 1995 BAY AREA TYPOGRAPHICAL UNION LOCAL 21, what labor historians call a conservative craft union, resolved in favor of full freedom for the African American political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal. In a letter to Pennsylvania’s governor, Local 21 argued that Abu-Jamal was “an innocent victim of a racial and political frameup” and branded his possible execution a “disgrace.”

Still more remarkable was what transpired during the filming of a recent segment on Abu-Jamal’s case by the ABC television newsmagazine 20/20. ABC let Abu-Jamal know of their plans to appeal to prison authorities in order to arrange an on-camera interview with him from Death Row. The feature promised to break the scandalous silence of the national media regarding the case and the still more comprehensive black-out of Abu-Jamal’s side of the case. With the possibility of making what was likely a last public appeal to save his own life, Abu-Jamal replied that he would of course be delighted to speak to ABC. He added, however, that no interview could take place while the network’s technicians, organized in NABET (another craft organization), remained on strike. He added precisely, “I’d rather die than cross that picket line.”

Those who produced the segment on Mumia, from star reporter Sam Donaldson on down, apparently had no qualms about scabbing on the strike. Nor did they choke on presenting a more or less pat recapitulation of even the most discredited police testimony in the case. Helping to sign the death warrant of a fellow journalist, 20/20 registered the utter abjection of “crusading journalism” in the U.S., crusading for network management, crusading for the police, crusading for the death penalty.

Although it will likely never grace the infotainment airwaves, the story symbolized by Local 21’s support of Abu-Jamal and by his incredible support of NABET, is a blockbuster commanding the serious attention of those of us trying to build a new labor movement. Abu-Jamal’s pro-labor journalism and activism, from Death Row with his days and columns grimly numbered, has been extraordinary. It has included not only a striking analysis of the importance of the recent strike by Philadelphia’s transit workers but also support for U.S. longshore unionists under threat of repression because of their militant refusal to service the Neptune Jade, a job action undertaken in solidarity with beleaguered British dockworkers in Liverpool.

Impressive labor support for Abu-Jamal has likewise developed, especially in the Bay Area, Chicago and New York City. In the April 1999 demonstrations around Abu-Jamal’s case in Philadelphia, New York City’s Workers to Free Mumia mobilized labor contingents and Local 1199 of the Health and Hospital Workers appeared in force. In the San Francisco march on the same day, 200 to 300 International Longshore and Warehouse Union members headed the crowd of 20,000, wearing union caps and carrying an ILWU banner. They chanted, “An injury to one is an injury to all. Free Mumia Abu-Jamal.” The San Francisco Labor Council endorsed the April action as did that of Alameda County and the California Federation of Labor. Organized teachers, postal workers, writers, transit workers, carpenters, hotel and restaurant workers and boatmen have likewise raised protests on Abu-Jamal’s behalf. So too have the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists (Region Six), the Coalition of Labor Union Women and the recently formed Labor Party. Internationally, “Justice for Mumia” endorsements have come from the Congress of South African Trade Unions and its powerful food and metal workers affiliates, the Transport and General Workers Union in London, a section of the General Confederation of Workers in France, organized British and Irish journalists, public employees in Canada and Australian telecommunications workers.

Most important by far, on April 24, 1999 the ILWU shut down all Pacific Coast ports, 30 of them, from Seattle to San Diego, in solidarity with Abu-Jamal and in support of the demonstrations on his behalf. The work stoppage, which came as a result of rank-and-file initiatives, occurred over heated management opposition and lasted the entire day shift. It was, according to ILWU president Brian McWilliams, the first officially sanctioned coastwide “stop-work” on the behalf of a domestic political prisoner ever. Messages of solidarity with the ILWU’s job action came from longshore workers in England, Cyprus, Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Japan. Rio de Janiero’s 100,000-member teachers’ union, which had itself stopped work in a two-hour show of support for Mumia on the previous day, also sent greetings.

THE EXTENT OF TWO-WAY SOLIDARITY between Abu-Jamal and the labor movement deserves publicity for the ways in which it gives the lie to recent slanders against the Free Mumia movement. According to these slanders, Abu-Jamal’s cause has irrationally attracted the support of a cult-like following of naive musicians, New Leftovers and internet geeks, who find it easier to champion the defense of a charismatic ex-Black Panther than to agitate around “real” class issues. (In an utterly overwrought Nation column, the populist film director Michael Moore recently offered a particularly distressing version of the charge that Mumia supporters are unserious.} That the Free Mumia forces enjoy significant labor support cuts against any such efforts to characterize the campaign as superficial and sentimental.

Moreover, labor support often finds its justification in the clear realization that police violence and race/class-based justice are workers’ issues, and in hard-headed analyses of the importance of building community/labor coalitions, Larry Adams, president of Local 300 of the National Postal Mail Handlers Union, has written:

Mumia is us. We are Mumia. . . .Trade unions exist for the right to defend democratic rights of working class people, due process, fair and equal treatment, freedom from police brutality — all of which is being denied Mumia in this effort at a legal lynching.

ILWU Local 10 executive board member Jack Heyman has emphasized that support for Abu-Jamal connects his union to both “the struggles of minorities here and the dockworkers’ movement internationally.” At the pro-Mumia demonstration in the Bay Area, he asked the 20,000 assembled, ““If the ILWU goes on strike, will you be there for us?” The response was resoundingly affirmative. However, the point which I wish to make in the balance of these pages goes quite beyond the argument that labor support for Abu-Jamal is significant, inspired and inspiring. My further claim is that labor’s solidarity with Mumia, and his with labor, best locate the terrain on which our boldest hopes for a new labor movement ought to be grounded. My friend George Lipsitz, inspired by both hiphop and R & B, has insisted that “What time is it?” ought to be a central question for anyone writing and thinking about class and race. For me, it is “Mumia Time” when new potentialities for the U.S. labor movement are under consideration.

This position is admittedly a pretty lonely one. For intellectuals writing about, and to some extent struggling alongside, U.S. labor, there has been little hesitancy over the last several years in telling what time it is. It is, for most, John Sweeney Time. From the 1996 Teach-In with the Labor Movement at Columbia University, to the founding of Scholars, Writers and Artists for Social Justice as a labor support group, to Stanley Aronowitz’s From the Ashes of the Old , Sweeney’s accession to the presidency of the AFL-CIO has been seen as the symbol of change, as the source of new space for progressive activity in the labor movement and as the grounds for a return to solidarity with labor by left-liberal academics. Thus Audacious Democracy, the volume of essays growing out of the Columbia Teach-In, proclaims in its introduction that Sweeney’s election constitutes the “best sign that the labor question is alive and well.”

To the extent that such a view restores hope and encourages the growth of concrete acts of solidarity with labor struggles, it is to the good, and the position that Sweeney is no Lane Kirkland is unassailable. Nonetheless, the “It’s Sweeney Time” position remains a problematic one. Sweeney’s “America needs a raise” platform turns out to be pretty thin gruel if we want to maintain, with Aronowitz, that the AFL-CIO is headed by “an insurgent.” Deeply nationalistic, Sweeney’s demand hearkens back to Samuel Gompers at his most economistic and narrow, not to the labor heroes who have held that workers need freedom, justice, and time to live. Even Aronowitz’s From the Ashes of the Old, the best of the “Sweeney Time” writings, partly reflects this narrowness. The labor anthem on which the book’s title plays envisioned bringing forth a “new world” from the old’s ashes, but Aronowitz instead describes the possibilities of building a somewhat stronger and more influential union movement from the ruins of the Meany-Kirkland leadership. Sweeney’s poor record on union democracy has meanwhile tempted some of his supporters to toy with idea that workers’ democracy is overrated in any case, and expendable.

USING SWEENEY TO MARK LABOR’S TRANSFORMATION AND POSSIBILITIES also coincides with a troubling nostalgia. Eric Foner and Betty Friedan, for example, voice hopes for a relatively unproblematic return to labor’s former glories in their Audacious Democracy essays. In the words of the former, the unions are poised to be “once again a voice both for the immediate interests of . . . members and the broader needs of of working- and middle-class Americans.” Such backward gazes fix on a long, mythic period in which, as Steve Fraser and Josh Freeman put it, class was the “primordial social question” — one whose “capacious embrace” could “absorb . . . the fate of women and children, racial and ethnic hatred.”

What, if instead, we took the remarkable solidarity between Mumia Abu-Jamal and the labor movement as the symbol of what a new labor movement promises? What if it is Mumia Time rather than Sweeney Time? Such a choice would mean several things. Most significant initiatives on Abu-Jamal’s behalf have been local ones, albeit with a great awareness of international connections. In most cases, pro-Abu-Jamal activities have been forwarded as a result of rank-and-file initiatives within locals, not as projects of the labor leadership. To think in Mumia Time rather than in Sweeney Time thus challenges us to entertain the possibility that the promises of a new labor movement cannot be envisioned if the focus remains national institutions and labor’s officialdom.

To emphasize that it is Mumia Time also opens critical questions concerning the state and labor. While the largest initiatives and greatest claims of success by the Sweeney leadership have centered on the election of more Democrats to national office, significant labor support for Abu-Jamal registers a deepening suspicion of state power. These mobilizations identify with an accused cop-killer who is utterly unsparing in his in excoriation of the complete corruption and unspeakable crimes of the government and of its deep complicity with corporate power.

Most impressively, the extent to which Abu-Jamal knows that he needs to identify with the labor movement, and that some in the labor movement know that they need to support him, signals what the working class movement is becoming and can be. In 1995, in a demographic shift which escaped the attention of mainstream, labor and radical journalists, organized labor became for the first time a movement in which white males are a minority. The Bureau of Labor Statistics counted 8.33 million white men in unions and 8.93 million African American, Latino and white female members. Crossing the 50% threshold produces no magical transformation, of course, especially while the leadership remains overwhelmingly white and male. Nonetheless, the trend is of real significance.

WITH AFRICAN AMERICANS AMONG THE MOST PRO-UNION SEGMENTS of the U.S. population, and with white males projected to constitute just 37% of the labor force by 2005, unions cannot survive, let alone grow, as an institution dominated by white men. The white male identity politics — taking forms ranging from hate strikes against the employment of workers of color, to anti-Asian rioting, to family wage campaigns, to the more pervasive inability to see that a “class” politics articulated so largely by white men could neither “absorb” nor even recognize questions of racial and gender justice — need not so crushingly burden the labor movement of the future. White trade unionists will often be a minority or near-minority in locals — the position from which they have historically moved in the most egalitarian directions. At the same time, the sharply limited but real protections which a white male membership base accorded the unions will apply less and less. The savage attacks on organizing by undocumented workers and on the diverse, pro-gender equity public employee unions presage a time when labor will represent those who are in every sense outsiders.

If it is Sweeney Time, rebuilding a Democratic Party majority and refurbishing labor’s image as a voice representing the U.S. middle class gives us a clear agenda and plenty to do. If it is Mumia Time, we would enter far more uncharted territory, in which we acknowledge that the labor movement cannot simply be rebuilt but must and can be built on new foundations. We would search, locally and internationally, for ways to embrace and nurture workers’ organizations which draw their poetry from the future and which express what Abu-Jamal has set out to capture in his journalism — “the voice of the voiceless.” The fight to keep Mumia’s own voice from being stilled, now more urgent than ever, is labor’s fight.

Abu Jamal’s defense requires urgent action and strong support, financial and otherwise. Donations may be made to [Donation info from 2000 article removed. The current info for Abu-Jamal’s support team can be found at freemumia.com.]