Lost to Idealism: The British Left Choose Rhetoric over Reality

In the United Kingdom, we are accustomed to progressives conducting their arguments in confident terms of complete inevitability. Progress is a one way street, and we are marching ceaselessly along it towards the end of history, almost without trying.

It is odd that people who would eschew totally any notion of God, or of some providence or direction behind the course of the world expect the march of political, and especially social reform, to continue unabated, propelled only by a curious momentum of its own. It's an attitude more befitting an obscure religious sect than a movement rooted in the cut and thrust of a modern democracy.

At its worst the new left, convinced of its pre-eminence, appears self righteous and hostile, lacking in perspective. In the Marxist Spiked magazine, Frank Furedi claims that “In the 21st century, university students are more likely to demonstrate on behalf of censorship than they are to struggle for freedom of speech”, as campuses across the country succumb to myopic and divisive identity politics. Meanwhile, Guardian writer Julie Bindel complains that the activities of the “new wave” of feminism seem “more like censorship than progressive politics” after a month of twitter fuelled bans, boycotts and forced apologies.

Behind this trend is the adoption of an abstract view of politics, replacing older theories rooted in the practicalities of life, or indeed reality itself. A movement increasingly based on social media and impassioned polemics does not win elections easily, and it leaves us perplexed when voters ignore the tide of history and give progress a bloody nose. We've started viewing actual political change as being born of lofty principle alone, instead of resulting from objectively measured material factors.

This is a rejection of the fundamental logical mechanism of cause and effect, and in politics and the media it is beginning to show. The black and white view of the world is encouraging mob-like tendencies in thought and action, as is evident from the aggressive culture wars now common in our society, which never really used to be a feature of British life. The left's new mindset is pushing them further from dialogue with the center, and from government. It is all a long way from how things used to be.

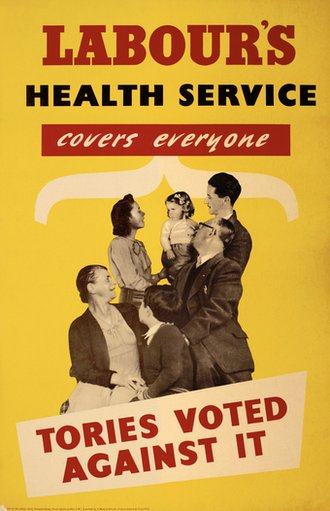

Nearly 70 years on, the 1945 government of Clement Attlee remains the greatest and most enduring source of inspiration to the British left. This was a government that created the NHS, nationalised heavy industry (taking some 20% of the British economy into public hands) and instituted numerous reforms to improve labour relations and workplace safety, and it remains a lodestar of the Labour movement in Britain. This year the annual conference of the Labour Party saw general secretary Iain McNichol invoking the “spirit of 1945” as the party gears up for the general election. Post-1945 saw such a comprehensive socialist restructuring that in retrospect it can be considered a revolution, made all the more remarkable for the consensus it enjoyed throughout society, even, to some extent, from conservatives.

But while our modern leftists believe that the mantle of progress forged in the struggle against Nazism should fall naturally to them as a matter of course, they ignore completely the very particular factors behind the creation of mainstream democratic socialism, assuming that a reformist consensus with particular historical origins will just perpetuate itself indefinitely into the future.

The post-war reforms owed their success to some very unusual circumstances. The violence and economic destruction of the war had impoverished the country, and a large proportion of the British establishment, including many conservatives, were convinced of the need for heavy reform to address the rampant hardship and inequality, a mood that was represented by the 1942 Beveridge Report, which declared war on the five “great evils” of squalor, ignorance, want, idleness and disease, and was perceived to give a green light to socialist government. It would have been impossible to create the NHS or the welfare state before the war, as the necessary consensus did not then exist.

The Labour Party's reforms had been given legitimacy by the war. “Nationalisation took place in an altered economic environment, brought about by the imperatives of wartime planning” wrote historian John Bew. “It was the universality of provision which was intended to form the basis of a new contract between citizen and state”, the need for such a change having been made clear during the conflict.

Furthermore, mobilisation, requisitions and the general move to a war footing set precedents for government intervention in society and the economy to a degree that would be very extreme today. For example, Labour officially nationalised Britain's railways in 1948, but they had arguably been under state control, more or less, since the beginning of the war. It was not as if the government had to force their point of view across in the way they would have to if they were to renationalise them today. Big state advocates won over the right wing by providing a patriotic basis for statism as a means of defeating the enemy, creating an entire generation of conservatives which lacked their modern counterparts' hostility to government.

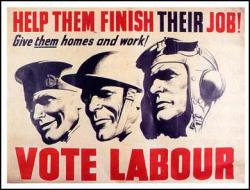

More importantly, the war years also provided Labour with their required voters. Millions of people, many of them already living with material deprivation, experienced bombing, conscription and food shortages, causing enough misery to drive ambitions for reform amongst the public. People became used to big government in their lives as they were bombarded with propaganda newsreels, public information posters and books, and were confronted with a highly visible military presence. Several million citizens served for years in the armed forces, some enjoying a standard of living that had been unattainable in civilian life. Many valued the communitarian attitudes created by the way society was ordered in the war years, and did not want to return to the inequality and hardship of the 1930s.

So if Attlee's effective but fairly moderate socialist reforms owed their success to an extreme historical context, what hope do we have today? It seems all great revolutionary change in history was the result of severe unhappiness at the foundations. The conclusion we are left with is that the old quarters from which change used to spring will no longer deliver, simply because modern western countries do not put their citizens under the same level of duress that they used to, or expect them to weather the poverty that was once commonplace. And while we would expect future reform to be driven by the marginalised elements of society, it is crass to regard their suffering as a reliable source of reformist momentum. Instead, we must look elsewhere and adapt to operating in a world that is simply more conservative, in that it has, so far, successfully avoided significant material want and conflict between established powers, and is therefore able to avoid radical change.

Western countries remain affected by inequality of income and opportunity, unemployment, poor education, substandard living conditions, inadequacies in the provision of medical treatment and welfare and unrepresentative government. But this doesn't mean that reform will spring automatically from this discontent. The evils of today are more insidious than the overt deprivation that prevailed until the mid twentieth century. And if it took a world war to create a modest welfare state, it will take a lot more to enact the change the modern left likes to think it could produce with a single term in government.

Today, we feel the loss of a statist consensus, and have certainly never seen support for government intervention to the degree that existed in the war era. The modern Labour Party is trying to reintroduce socialism with no effort at collectivisation or nationalisation, but rather with liberal rhetoric backed up by vague promises to safeguard an unambitious welfare settlement. Its languid efforts are more about being seen to say the right things than establishing de facto socialism on the ground.

Over the past few decades, union membership has decreased by several millions, participation in elections has declined, and billions of pounds' worth of assets has left the auspices of the state through privatisation. It has damaged both the potency of the state and of communitarian values in society. Trying to introduce socialism to a post-thatcherite society, from which collective values have been absent for years is doomed to fail, unless Labour first commits to restoring a sense of collective responsibility that the 1940s took for granted. Future economic and social reforms will have a secure foundation when mass participation in politics is once again the norm, union membership is back up to its pre-1980s levels and Labour party membership is in the millions instead of the current 190,000. The left should have used their time out of government to work at these goals, or at least accept the scale of the problem. Expecting the initiative to swing back to the progressive camp of its own accord in a society that has been built by neoliberalism just isn't enough.

*The author is an active member of Britain's General, Municipal and Boilermakers' Union.