The Workers Party’s Contradictions and the Contours of Crisis in Brazil

Election day came lazily in Santarém, a mid-sized city and trading entrepôt at the junction of the Amazon and Tapajós rivers, the halfway point between Amazônia’s primary metropolises of Manaus and Belém. The internet was out of service in this sleepy Amazonian town, as were two out of the four major cellphone carriers, and the streets were nearly empty. I encountered a group of men singing songs on the waterfront, reclining under one of the few shaded barracas that gave them respite from the relentless sun. I asked one of the men—who, like many who work in the precarious river trades, walked on crutches and nursed an amputated leg—where people were going to vote. After he told me about a few locations, which all seemed too far for me to walk to in the suffocating heat, I asked him when he was going to go vote. “Not until the late afternoon—I don’t like the long lines,” he said. “Not like it’s that important anyway; I’m going to vote branco” (leave the ballot blank).

Election day came lazily in Santarém, a mid-sized city and trading entrepôt at the junction of the Amazon and Tapajós rivers, the halfway point between Amazônia’s primary metropolises of Manaus and Belém. The internet was out of service in this sleepy Amazonian town, as were two out of the four major cellphone carriers, and the streets were nearly empty. I encountered a group of men singing songs on the waterfront, reclining under one of the few shaded barracas that gave them respite from the relentless sun. I asked one of the men—who, like many who work in the precarious river trades, walked on crutches and nursed an amputated leg—where people were going to vote. After he told me about a few locations, which all seemed too far for me to walk to in the suffocating heat, I asked him when he was going to go vote. “Not until the late afternoon—I don’t like the long lines,” he said. “Not like it’s that important anyway; I’m going to vote branco” (leave the ballot blank).

The results for the first-round vote were not to be released until 7:00 that evening, but many people, per the opinion polls, were expecting a second-round runoff between incumbent Dilma Rousseff of the Workers Party (PT) and dark-horse candidate Marina Silva, an ex-PT maverick whose humble origins, evangelical ties, and environmentalist credentials earned her a Cinderella-esque ascendancy after the sudden death of running mate Eduardo Campos, the original presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of Brazil (PSB)1. So it came as a bit of a surprise when Marina ended up in third place with 21 percent of the vote, and the runoff was set between Dilma, who finished first place with 41 percent, and the conservative pro-business candidate Aécio Neves, who took 33 percent.

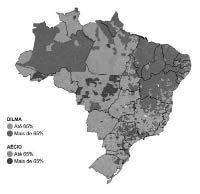

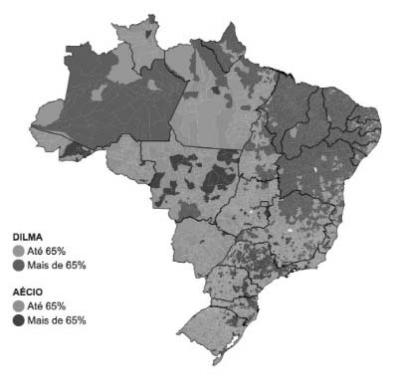

This unexpected result opened up the potential for a return, after 12 years of PT rule, to the blatantly pro-market, oligarchic café-com-leite politics of old. The traditional elites smelled the proverbial blood in the water, and in the intervening weeks before the second-round vote, the gloves came off of the conservative offensive. The PT’s strong constituency in the Northeast, in particular, became the target of vicious and racist attacks from Aécio’s party, the PSDB, and its elite allies. Fernando Henrique Cardoso, former president of Brazil and current head of the PSDB, claimed in an interview that Northeasterners were too ignorant to vote, sparking a wave of racist attacks against nordestinos.2 In one of the worst incidents, a group representing over 100,000 health professionals promoted the chemical sterilization of Northeasterners, calling for a “holocaust” amongst PT voters.3 In the last days before the second round, the elite offensive against the PT even assumed a perverse affinity with global protest movements, as the Economist claimed a “cashmere revolution” was on the rise.4

In the runoff vote, which took place on October 26, Dilma squeaked out a three-and-a-half point victory over Aécio Neves, winning 51.6 percent of the vote and a historic fourth term for the PT. This narrow win, secured in part through a dramatic last-minute mobilization of artists, social movements, academics, and other prominent citizens in support of Dilma, was celebrated as a victory for left progressive forces in Brazil. This mobilization certainly held the line against the shamelessly neoliberal “tucanos,” as well as the entrenched oligarchies and financial elites who barely concealed their salivating at the first hint of a return to power. But for many of the informal workers, favelados, and others I spoke to on the streets of Brazilian cities who voted branco and/or opted out altogether in the first round, holding the line against a right-wing revolt is not enough to counteract a pervasive sense of disillusionment with a stagnant economy and an ineffective government.

In the context of the multiple potential crises currently confronting Brazil, the narrow second-round result perhaps signals less of a victory for the left than a serious wake-up call for a Workers Party that has grown complacent in its relative hegemony. Brazil’s current social and political trajectory—from the explosive yet ambiguous political character of the 2013 protests, to a victory for Dilma that was far too close for comfort—perhaps reflects the fact that the PT’s politics of triangulation between the needs of the people and the demands of global capital has reached a critical limit. In the face of a renewed offensive from national right-wing elites and international “market forces,” the PT must do more than simply hold the line in these next few years if a “left” government is to survive in Brazil.

The Geography of Power

Brazil’s electoral, economic, and historical geography is of central importance in understanding the nation’s political conflicts, dilemmas, and prospects for social change. Since the late nineteenth century and the collapse of the slave-based sugar economy, the contours of oligarchic rule in Brazil have historically been shaped by the politics of “café-com-leite” (“coffee with milk”)—a term originally referring to the political dominance of coffee and dairy interests from Brazil’s Southeastern states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais in the early twentieth century, and whose legacy has continued to characterize the disproportionate influence of the rich and powerful Southeast in national politics. In fact, some commentators in the Brazilian press noted that Aécio Neves, who was governor of Minas Gerais until his presidential run, suggested a literal return to the “café-com-leite” politics of old by choosing a Paulista, Aloysio Nunes, as his running mate.

With the 2003 election of President Lula, a native Northeasterner, the PT government’s domestic policies reflected a shift in priorities not only towards the working class and poor, but particularly the rural poor in the semi-arid Northeast, which was at the time the largest contiguous concentration of poverty in the Americas. For the first time, the poor of the North and Northeast not only gained material support, but a degree of visibility and influence on the national scene. Little wonder, then, that this population—ignored for centuries by Southeastern elites—has continued to vote overwhelmingly for the PT.

The PSDB’s fear of the poor and dark-skinned voter rests not on their ignorance, but on the fact that the poor actually do understand their interests, and have experienced the material benefits of their votes. Voting is mandatory in Brazil. This fact is often acknowledged almost as an afterthought in U.S. media reports, but its significance for electoral politics is just as often overlooked. In Brazil, a citizen must show an active voter registration card, or título, in order to obtain formal employment, open a bank account, qualify for loans, or receive government services or benefits.

On one level, this system of compulsory voting encourages democratic participation from citizens, and draws a much tighter relationship of accountability between politicians and their constituencies, particularly at the local level. Thus, even (and perhaps especially) in a multi-party system such as Brazil’s, communities have real ability to wrest material concessions, such as much-needed infrastructure or social services, from their political representatives through the power of the vote. For example, I recently visited a friend who lives in a favela in Salvador, Bahia, and noted that the streets had recently been paved; a banner announced that this was the work of the local PT deputy, who I’m sure received a good share of the vote from this community in return for completing this public service.

It is within this system that the PT has retained power on the demonstrative merit of its social programs. Initiatives such as Bolsa Família, a conditional cash transfer program for poor families, and Fome Zero, an anti-hunger campaign, have indeed significantly reduced absolute poverty in Brazil, especially in the very poor North and Northeast regions. Especially in the sertão—the semi-arid rural interior of Northeast Brazil, currently in its third year of severe drought—Bolsa Família payments can mean the difference between life and death for the millions of small farmers, quilombolas (communities of descendants of escaped slaves), and itinerant agrarian workers that live in the region. As I traveled through the Northeast by bus this past month, I heard many residents passionately defend the PT’s social policies as a vital lifeline for a population otherwise abused and abandoned by successive governments throughout Brazil’s history.

The PT’s Contradictions

and Challenges for Brazil

The material concessions granted—and won by communities—through the mandatory voting system are important and real; but as a political strategy, these local victories fail to amount to any kind of systemic process of democratically driven social transformation. In fact, it easily can, and in many cases has, simply become a game of capturing votes. Looking at Brazil from the outside, the PT’s importance as a “left” government in Latin America is quite apparent on an global and regional level; but on the state and local levels, PT representatives and functionaries often blend in far too easily with the oligarchic old boys’ networks that have always prioritized private profit over public good.

As Amazonian journalist Lúcio Flávio Pinto recently wrote, “The people are grateful to those who have discovered them, who remembered them, and who have done far more for them than ever before. This is the merit of the PT government. Yet it is a relative merit, conditioned by historical circumstances and individual conditions.”5 The historical conditions under which the PT government has lifted nearly 40 million citizens out of poverty also underlie the contours of the current crises facing Brazil. In the last few years, the PT’s “neo-developmentalist” strategy of triangulating between neoliberal macroeconomic policies that favor agribusiness and financial markets on the one hand, and nominal wealth redistribution through social programs on the other, has reached a number of “structural limits,” in the words of Movement of the Landless leader João Pedro Stedile.6

The PT’s internal contradictions are playing out in several dramatic ways, with consequences that reach far beyond the local contexts in which they occur. The revolts of 2013 were just one manifestation of the economic dilemmas that Dilma faces in her second term. Brazil’s spectacular economic growth in the first decade of the 2000s slowed throughout Dilma’s first term in office, technically entering recession in 2014. While Dilma has taken a stand against the standard neoliberal policy prescriptions for austerity that have devastated economies elsewhere, she had made some modest attempts at austerity in the first year of her presidency that, along with the ludicrous levels of spending for the World Cup and Olympics, created the conditions for the 2013 protests.

At the same time, her refusal to fully embrace free-market policies—and Aécio’s willingness to do just that—have made the PT a target for international “economic terrorism.”7 Dilma’s re-election in the second round provoked a harsh rebuke from global capital; the national stock market tanked and Brazil’s currency fell close to its lowest point in nearly ten years, leading to the Wall Street Journal’s brazen claim that “the world voted on Brazil, and … the result was a resounding no confidence.” While about 2,500 far-right demonstrators marched in São Paulo for Dilma’s impeachment—a relatively small protest but widely covered in global corporate business publications—a petition at the White House website asking for U.S. intervention to force Dilma out of office reached over 100,000 signatures.8 This election also saw a sharp rightward shift in Congress, to the most conservative legislature since the military coup of 1964—with the PT losing 18 congressional seats to the PSDB, PSB, and smaller parties to its right, and extreme right-wing representatives such as Jair Bolsonaro and Luiz Carlos Heinze receiving a greater share of the vote in their respective states.9 With a potential resurgence of right-wing political elites waiting in the wings, it is possible that the stage is being set for an all-too-familiar replay of Latin American regime change through the Washington consensus’ economic hit men.10

Another set of challenges for the PT on a national level are the ecological consequences of its agriculture and conservation policies in the Amazon, as well as the dry-forest areas of the Cerrado, where international scrutiny and Amazon-style environmental protections are practically nonexistent. In these areas, the PT has overwhelmingly favored large-scale agribusiness interests, including the explosively expanding soy industry on which much of Brazil’s export economy has come to depend.11 The “ruralista” bloc of big agribusiness interests and their representatives in Congress have facilitated the rapid and incredibly violent expansion of sugarcane, soybean, and cattle production into indigenous lands, extractive reserves, and other protected areas of the rainforest.12 Dilma herself, in 2012, signed into law crucial changes to the vital Forest Code, which effectively reduced the percentage of agricultural land that must remain under conservation by law13; and in 2014 openly declared her support for re-election of the leader of the most important agribusiness lobby within Congress, Senator Katia Abreu.14

These and other collusions with agribusiness have resulted in a whopping 190-percent increase in deforestation since the easing of the Forest Code, compared with a steep decline in deforestation over the previous decade.15 Evidence now points to a connection between deforestation in the Amazon and an unprecedented drought in—of all places—São Paulo, where millions of residents in one of the world’s largest megacities could run out of water in the next few weeks.16 Sadly, here too, the politics game has undermined the everyday lives of poor and working-class Brazilian citizens, as PSDB governor Geraldo Alckmin faces criticism and protests over having withheld critical action on emergency drought measures until after the October elections.17

In these contexts (and others), Marina Silva’s sudden rise in the polls made a certain amount of sense. While her politics were relatively vague and inconsistent in some ways—and quite clearly neoliberal in others—her campaign rode a wave of popular anti-PT sentiment and disillusionment with politics-as-usual that appears to stem not simply from right-wing media manipulations and accusations of corruption, but also from the material contradictions of a left in power that has not, and perhaps cannot, go far enough in its current configuration and “neo-developmentalist” orientation.

Fortunately, for now, Brazilians have kept the reactionaries at bay, and vital space still exists for crucial debates about the nation’s future. Social movements, unions, peasants and poor, working class, Afro-descendent, and indigenous communities throughout Brazil can still come together—as they had once before, in the creation of the PT—and demand a real program for progressive social change. Whether or not such a program is still possible within the PT apparatus is a contested issue, with many on the Brazilian left advocating for and creating alternative forms of left politics and representation. What is clear is that in the current conjuncture, further capitulation to the neoliberal status quo is unsustainable in either the social or electoral arenas. Agrarian reform, equitable urban development, protection of indigenous lands, and socio-environmental policies and protections should lay at the heart of a renewed strategy that can inspire a revitalized left to survive and thrive, in power, in the face of the great challenges that loom on the horizon.

Footnotes

1. Silva joined the PSB and Campos’ campaign after her attempt to create an alternative party, Rede Sustentabilidade, was denied by the national electoral courts.

2. Eduardo Guimarães, "Entrevista de FHC estimulou ataques a nordestinos na internet," Blog da Cidadania, Jul. 10, 2014.

3. Carolina Garcia, "Comunidade médica prega holocausto no Nordeste em campanha contra Dilma na web," Último Segundo, Jul. 10, 2014.

4. "Pre-election Spending in Brazil: A Final Splurge," The Economist, Oct. 1, 2014.

5. Lúcio Flávio Pinto, “Sem Líderes,” Jornal Pessoal (No. 570, October 2014).

6. Celso Horta, "Stédile Rebukes the Dilma Government's Agrarian Reform Program," Friends of the MST.

7. Pedro Paulo Zahluth Bastos, "O terceiro turno já começou. O austericídio também?" Carta Maior, Oct. 28, 2014.

8. Marianna Rios, "Petição anti-Dilma recebe 100 mil assinaturas no site da Casa Branca," Correio Braziliense, Nov. 3, 2014.

9. "PT perdeu 18 cadeiras na Câmara; PSDB ganhou 11 e PSB 10," Viomundo, Oct. 5, 2014.

10. Kenneth Rapoza, "In Brazil, Some Want Military Dictatorship Back," Forbes, Nov. 1, 2014.

11. James Petras and Henry Veltmeyer, Extractive Imperialism in the Americas: Capitalism’s New Frontier (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2014).

12. "Toxic: Amazon," Vice.

13. "Brazil's Congress approves controversial forest law," BBC, Apr. 26, 2012.

14. "Dilma apoia Kátia Abreu," video on YouTube here.

15. Joaquim Moreira Salles, "Amazon Deforestation Spikes 190 Percent After Long Reported Decline," Amazon Watch, Oct. 20, 2014.

16. Adriana Brasileiro, "São Paulo running out of water as rain-making Amazon vanishes," Reuters, Oct. 24, 2014.

17. Paula Felix, "Protesto contra falta de água ironiza Alckmin em frente à Sabesp," O portal de notícias do Estado de S. Paulo, Nov. 1, 2014.