When Sri Lanka Operated Workers’ Councils

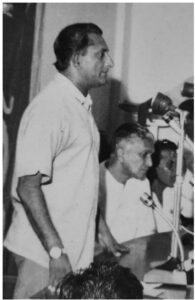

Anil Moonesinghe addressing a meeting at the Ceylon Transport Board. Leslie Goonewardena is sitting on his left. Image courtesy of Vinod Moonesinghe.

The origins of Sri Lanka’s workers’ councils can be traced back to developments in Yugoslavia under Joseph Broz Tito.

On June 28, 1948, the Stalinist League of European Marxist-Leninist parties, the Cominform, expelled Yugoslavia from its ranks. Having deviated from the Stalinist line, Tito could have expected little else. Facing a blockade from his former allies, he had to rechart his country’s course.

Tito did this by institutionalizing what would later be called “market socialism.” Initially criticized as a deviation from the Communist line, it was later embraced not just by anti-Stalinist reformists, but also by those advocating a path between capitalism and Communism, particularly in what was once called the Third World. Tito’s involvement in the Non-Aligned Movement in later years helped bolster his credentials as a proponent of this line.

One significant innovation of Yugoslav market socialist reforms was the formation of workers’ councils. The logic behind these councils was not immediately clear, and it was, for obvious reasons, viewed as an aberration by Stalinists. Nevertheless, it was based on an unmistakable Marxist body of theory, dating back to Engels’ Anti-Dühring:

State interference in social relations becomes, in one domain after another, superfluous, and then dies out of itself; the government of persons is replaced by the administration of things, and by the conduct of processes of production. The state is not “abolished. It dies out. This gives the measure of the value of the phrase “a free people’s state,” both as to its justifiable use at times by agitators, and as to its ultimate scientific insufficiency; and also of the demands of the so-called anarchists for the abolition of the state out of hand. (Anti-Dühring, Part III, Chapter II)

Engels contended that the post-revolutionary state would cease intervening in and mediating social relations between people. With the “dying out” or “withering away” of the state, the means of production would be managed and controlled by the proletariat itself, leading to a true “dictatorship of the proletariat.”

Similar views were sometimes pronounced by the Bolsheviks as well. “The implementation of all these measures,” Lenin once contended, “is possible only if all the power in the State passes to the proletarians and semi-proletarians.” Upon coming to power, of course, Stalin abandoned any pretenses: instead of greater power for the workers, he resorted to bureaucratic repression and administrative commands, dissolving such projects as the Kuzbass Autonomous Industrial Colony.

Tito institutionalized workers’ councils as a counter to Stalin’s policies. For that, certain reforms had to be in place. In response to the Stalinist advocacy of a centralized bureaucracy, for instance, Tito embraced devolution. In May 1949 his government granted autonomy to local governments. Political decentralization led to increased worker participation: in 1950, a year after devolution was implemented, the Yugoslav National Assembly legalized worker self-management schemes. The Yugoslav state moved away from direct management of productive enterprises.

This was bound to have an impact on left movements elsewhere, especially in the Third World, including Algeria, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Mexico. Arguably the most striking use of workers’ councils as part of a wider strategy of fomenting revolution through working-class mobilization, however, was to be found in Sri Lanka.

A Brief History of the Sri Lankan Left

Sri Lanka—Ceylon under British rule (1796-1948)—had been a plantation colony for over 150 years. The imperialist experiment of breeding a class of people born there, but imbued with proper British manners and culture, had succeeded in the tiny island colony more than it had in India. After British forces annexed the Kandyan kingdom in 1815, they faced, and brutally crushed, a series of peasant uprisings, the most serious of which took place in 1848, also a time of revolution in continental Europe. In the aftermath of the 1848 uprising in Ceylon, the colonial government shifted its strategy from bureaucratic rule to co-opting the country’s elites, especially the newly emerging middle-classes.

The result was the formation of a bourgeoisie that, in effect, identified their interests with the interests of the colonial state, and worked on behalf of the latter. The nature of this colonial bourgeoisie not surprisingly determined the course of anti-colonial agitation in the island in the years to come. The conventional Communist line held that in colonial and semi-colonial countries, the national bourgeoisie would lead a democratic revolution, and then overthrow imperialism. In contrast to this view, Leon Trotsky contended that the “national bourgeoisie” was too weak to combat imperialism. It was the working class, he argued, and not the bourgeoisie, that had to face and dismantle imperialism.

The Trotskyist perspective fit the situation of the Sri Lankan bourgeoisie rather aptly. As former Sri Lankan Marxist writer and commentator, Regi Siriwardena, noted, “Trotsky could even have taken the Ceylon bourgeoisie and its political leadership as a demonstration of the incapacity of that class to play a militantly anti-imperialist role.”

In the early years of the 20th century there had been a series of struggles, strikes, and movements led by workers in Ceylon. But devoid of leadership, they petered out. The Sri Lankan Labour Party was founded in 1928; however, the depression of the 1930s caused the movement to rupture, during which a new generation of radicals began to question Labour Party leadership.

These radicals, recently returned from Europe, formed the Lanka Sama Samaja (Equal Society) Party (LSSP) in 1935. They declared as their aim the achievement of complete national independence (as opposed to the bourgeoisie’s call for constitutional reform), the socialization of the means of production, and the abolition of all forms of inequality “arising from differences of race, caste, creed, or sex.” Other partial demands included the enactment of the eight-hour day, the passing of a minimum wage, and the abolition of child labor.

From its beginning, the LSSP identified the weak and embryonic nature of the bourgeoisie. Concentrated within the Ceylon National Congress, the bourgeoisie found itself incapable of playing the militantly anti-imperialist role that its Indian counterparts were playing through the National Congress. The LSSP did not articulate its view of the elite along Trotskyist lines, especially since a section agreed with the Stalinist view. Nevertheless, a section in the party began to question the orthodox Communist view of colonial society.

In 1940, a mere five years after its establishment, the Lanka Sama Samaja Party split over the Third International. This was compelled by developments in Europe, in particular the Moscow Trials, the Popular Front, and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, that had put in doubt the correctness of Stalin’s leadership.

The group that sided with the Fourth International, the Trotskyist faction, rejected any alliance with the bourgeoisie. It pinned its hopes for a revolution on the workers rather than on the Ceylon National Congress. The Communist faction, by contrast, opted to side with the latter during the Second World War. It was against that backdrop that, in the post-war period, the LSSP began looking at countries charting alternative paths. This included the Yugoslav reforms, especially Tito’s labor reforms.

The Establishment of Workers’ Control

In its manifesto for the general election of 1951, the LSSP called for “the establishment of workers’ control in all industrial establishments and workplaces.”

One of the most fervent advocates of this line was the LSSP’s General Secretary, Leslie Goonewardena. Goonewardena contended that Tito’s reforms constituted “an original contribution to socialist thought and practice.” Regardless of differences between the two societies, he found it suitable for “an underdeveloped country embarking on socialist construction.” That was no doubt informed by the Party’s attitude to the Soviet Union, which it saw, and denounced, as a “degenerated workers’ state.”

Goonewardena also advocated workers’ councils as a way of reforming the colonial bureaucracy. To this end, the LSSP changed its strategies. In the early 1960s it decided, controversially, to enter into electoral arrangements with the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, a nationalist formation based on the backing of small capitalists that had come to power in 1956, in a bid to upend the bourgeoisie, which had by now shifted its support from the National Congress to the United National Party (UNP), under the leadership of D. S. Senanayake and his son, Dudley.

In 1964 the LSSP adopted a program for workers’ councils as part of its agreement with the SLFP, so as to bring people into “participation in the process of government.” The decision to enter into an electoral agreement with the SLFP proved to be controversial in the long term, though advocates of the agreement argued that the left could foment revolution in the country only through electoral strategies.

This led to a split in the LSSP, and the latter’s expulsion from the Fourth International, but it also led to discussions about the reforms it had recommended, so much so that five years later, even the UNP could propose “worker participation in managerial functions.” The Communist Party, which had rejected the LSSP, joined the latter in a common front against the UNP.

On the basis of a common program adopted in 1968, the SLFP-LSSP-Communist Party coalition that came to power in 1970, under the United Front label, adopted a series of reforms that paved the way for workers’ councils and advisory bodies at state enterprises. This was necessitated, in part, by the growth of public corporations and a rise in the number of employees at these corporations.

Weaknesses and Strengths

The councils and advisory bodies had very clear aims. Both were entrusted with powers to “check waste, indifference, and sabotage.” The leftist political academic Wiswa Warnapala has noted that they were also “expected to bring down the cost of living and narrow the gap between the upper and lower rungs of the administration.”

Among the institutions that took the lead in forming workers’ councils was the Ceylon Transport Board. Under its Chairman, Anil Moonesinghe, who had served as Transport Minister in 1965, issues like the utilization of capital equipment and reduction of overtime came within the purview of the councils.

In 1970, two French Marxists, L. Schmidt and D. Maurin, spent several months in Ceylon examining these councils. Observing their formation and mobilization in the Transport Board, they commented that under Moonesinghe’s leadership, the councils had helped in “cutting down costs, improving services and timetables and better upkeep of the buses, cutting out corruption, and better use of new buses,” leading to a jump in revenue “from 600,000 rupees a day in April to 800,000 a day in August.”

On a more sober note, they also wrote that the SLFP’s right-wing, headed by the leader’s own nephew, “proposed a White paper that the presidents of the workers’ councils and people’s committees be appointed by the Minister concerned,” a move antithetical to the spirit of such reforms.

To be sure, these organs did suffer from several weaknesses. Apart from being subject to Ministerial oversight, they also led to tensions between the councils and trade unions, the latter which may have felt their powers usurped through the granting of autonomy to employees. The government did not ignore their concerns; consultations were frequently held to prevent tensions from flaring up and defeating the aims for which these organs had been set up. Such tensions, however, did not disappear, in part because trade unions were led by political parties that prioritized their own interests.

An Ultimatum

Owing to a loss in popularity due to food shortages and scarcities, the SLFP was defeated by the UNP in 1977. The new regime enacted neoliberal reforms that had their antecedents in Chile under Pinochet and Egypt under Sadat. Perhaps needless to say, the councils were abandoned. The passing of an Employees’ Councils Act No. 32, in 1979, may have bolstered hopes about their continuation, but this did not happen.

In 1997, a newly returned SLFP alliance, albeit one that modelled itself along Third Way Centrist rather than socialist lines, issued a call to re-establish workers’ councils. This, too, fell into neglect and has not been revived since.

What these initial reforms would have led to, we may never really know. But their achievements were considerable. By 1974, 212 councils had been formed, involving a workforce of 135,000 in the public sector. The labor studies scholar Gerard Kester called them “an important innovation in social political development.” They were also praised by the International Labor Organization. Whether or not these pointed to an alternative road to socialism, they became a prototype for worker empowerment.

In the country of their birth, Yugoslavia, on the other hand, workers’ councils achieved a mixed record: as James Robertson, of the University of California Irvine, puts it in an essay in Jacobin (July 17, 2017), the contradictions that the Yugoslav model generated, including uneven rates of growth between the country’s regions, eventually led to their collapse.

Yugoslavia’s shift to market socialism, even under the guise of self-management for employees, could not stop its free-fall after 1989. By then, Robertson notes, “[c]rippling foreign debt, structural adjustment measures enforced by the International Monetary Fund, and economic collapse amplified the centrifugal pulls of foreign markets.” The result, which came to fruition in the new millennium, was the disintegration of an entire country.

In Yugoslavia, workers’ councils floundered under the contradictions of Tito’s alternative to Stalinism; in Sri Lanka they were hemmed in by the contradictions of an alliance between working class and small capitalist parties. Put simply, as in Chile under Allende, and Egypt under Nasser, the bourgeois state in Sri Lanka could not withstand small capitalist elements coexisting with a radical left.

What happened next was tragic. The socialist alliance that won elections in 1970 turned to the right five years later, when, over a number of issues, the two main left parties in the alliance, the Lanka Sama Samaja Party and the Communist Party, were expelled by an increasingly authoritarian and nepotistic Sri Lanka Freedom Party. This detour to the right served as a prelude to the SLFP’s defeat in 1977, in an election that was won by the even more rightwing neoliberal United National Party.

However, whatever criticism one can make of the LSSP and the Communist Party for their decision to form an alliance with the SLFP, it was through this alliance that several important reforms came to pass. The workers’ councils held the promise of such a reform, as did the advisory bodies. Yet as with every radical piece of legislation after 1970, including land reforms, these would eventually, and tragically, not come to pass.