Solidarity Report from Standing Rock

[Editors’ note: The struggle at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) was one of the major political mobilizations of 2016, combining the demand for Native rights with the call for environmental justice. New Politics asked Nancy Romer to cover these events for us. She was at Standing Rock from November 10-15.

[Editors’ note: The struggle at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) was one of the major political mobilizations of 2016, combining the demand for Native rights with the call for environmental justice. New Politics asked Nancy Romer to cover these events for us. She was at Standing Rock from November 10-15.

Her initial report and her article on the meaning of the victory achieved on December 5—and the struggle that still remains—have been posted on the New Politics website. Here we print two more of her dispatches from the scene, showing some of the day-to-day dynamics of standing with Standing Rock.]

In this report I will try to give you a sense of what it was like to be at Standing Rock. Tonight completes my third day here. The weather has been mostly cold but very sunny. The colors, the sky, but most of all the people are startlingly calm and beautiful. The Standing Rock encampment is defined as a prayer site, a place to contemplate and to appreciate nature, “the creator” (not my words), and each other. The indigenous people here, from just about every tribe in the United States and some from Canada, are so welcoming and warm to outsiders. They repeatedly say how much they appreciate the presence of non-indigenous folks and how they want to share with us. They are strict on the rules: no violence of any kind; no drugs, alcohol, or guns; respect for indigenous ways; making oneself useful.

The vast encampment contains four or five separate but connected camps, some on the Sioux reservation land, others outside. The largest one is immediately off reservation land, Oceti Sakowin Camp; it is the one in which most of the activities happen. The others are either defined by age—elders or youth—or vary by activity. There is a “Two-Spirit Camp” for gender non-conforming people, a traditional and accepted group in Native culture. We spend most of our time at Oceti, but today I took a long walk and visited two of the other camps just to get a flavor of them. “NO DAPL” stands for “No Dakota Access Pipeline,” and signs with the slogan are everywhere, as is the phrase “water is life.” There is a religious feel to the camps and great respect all around. In many ways this is a very old-style indigenous encampment, and in many ways it feels like a post-revolutionary or post-apocalyptic future. The pace is slow though everyone seems to move with great purpose. People jump in and do the tasks that seem to be needed: cooking, cleaning, helping each other to put up a yurt or a teepee, chopping wood, tending fires, washing dishes, and offering legal, medical, or psychological help. Cell and internet service is miserable and probably interfered with by the constant drones that fly above the camps.

On Friday morning, day two of my trip, I attended a brilliantly presented orientation to the camp. One of the presenters was Maria Marasigan, a young woman I know from our shared days in the Brooklyn Food Coalition. It was the best anti-racist training for allies that I have witnessed: It was succinct, not guilt-trippy, and very direct. The three main concepts are: indigenous centered, build a new legacy, and be of use. Presenters shared the Lakota values that prevail in the camp: prayer, respect, compassion, honesty, generosity, humility, and wisdom. For me the most impactful point was respect. They defined that as including slowing down, moving differently with clearer intention and less reactivity. They suggested asking fewer questions and just looking and learning before our hands pop up and we ask to take up space. They clarified a gendered division of behavior and practice, including asking “feminine identified” women to honor traditional norms by wearing skirts during the sacred rituals (including in the cooking tent) and for women “on their moons” to spend time in a tent to be taken care of and rest if they choose. Somehow it seemed okay, actually respectful, not about pollution and ostracism. While I was helping out in the cooking tent—my main area of contribution—an indigenous woman came by with about ten skirts and distributed them to the mostly women in the cooking tent, explaining that cooking is a sacred activity, and we gladly put them on. It served as an extra layer of warmth over my long underwear and jeans. It was not what I expected but it seemed fine to all of us. We just kept chopping away at the veggies.

Later that day I attended a direct-action training that was also quite thorough and clear. Lisa Fithian, an old friend from anti-war movement days, led the training and explained how to behave in an action and how to minimize police violence. Lisa, along with two other strong, smart women, one Black and one Native, laid out a plan to do a mass pray-in in town the next day. My friend and travel companion Smita and I both felt that we couldn’t risk arrest and decided not to join that direct action but to be in support in any way we could. At 8 the next morning about a hundred cars lined up in convoy formation at the exit of the Oceti Sakowin Camp, each with lots of passengers—including some buses and minivans—and went into Manwan, the nearest town. The indigenous folks formed an inner circle and the non-indigenous formed a circle around them. The indigenous folks prayed, sang, and danced. The tactic was exercising freedom to practice their religion while protesting the Dakota Access Pipe Line. No arrests were made despite massive police and drone presence. One local man tried to run over a water protector, but she jumped aside; the man had a gun but was subdued by the cops. Lots of videos were taken, and the man was taken to the local jail.

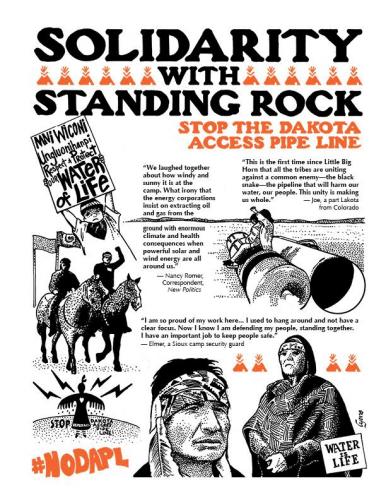

On Saturday I finally got a press pass, having been requested by New Politics to cover the encampment. That gave me the right to take photos (otherwise not allowed), but with limitations: no photos of people without permission, or of houses or horses, again, without permission from the people with them. I set out to interview people at the various camps and to get a sense of what people were planning to do for the winter. I spoke with Joe, a part Lakota from Colorado who had been raised Catholic and attended Indian residential schools, taken from his parents by the state because it doubted the ability of the Native community to raise their own kids. He said it was brutal. When asked why he was here, he replied, “This is the first time since Little Big Horn that all the tribes are uniting against a common enemy—the black snake—the pipeline that will harm our water, our people. This unity is making us whole.”

At Rosebud camp, just about one-half mile from Oceti, I discovered a group of people building a straw-bale structure that was destined to become a school. Multi, an architect from Southern California, took a break to tell me how they came to create this project with the full collaboration of parents and kids in the camp. Their project grew out of a team of people from Southern California who are builders and designers and who use earth and straw as materials, creating almost no carbon footprint and providing both strength of structure and extraordinary insulation—very important for the windy and cold winter ahead. Multi told me,

We didn’t want to bring the colonialist idea of what was needed and just tell people at the camp. We spent five days gathering ideas from people at the camp as to what they needed. They decided on building a school for the many kids who might stay the winter or come and go over time. The parents and kids helped to design the structure with the builders. All the decision-making was “horizontal,” engaging everyone with equal voice, avoiding hierarchy. It will be a one-room school house, with nooks for specific tasks, and will serve K-8th graders.

A teen center is being built nearby. When I visited, there were five women and one man working on the project and they welcomed any help they could get to finish the project before the cold set in. When I asked Multi why she was doing this project she said, “For me this is about coming together as a global culture, a people who have the resources we need for future generations. We are here to protect our futures together. Building a school house is a manifestation of that ancient technology for our future together.”

Down the road I met Danielle, who was helping to build a multipurpose center housing a kitchen, dining area, and meeting room. She told me that “this is all about the water and who lives downstream. We are testing a new economic system that requires governance, self-governance from the ground up. The needs must evolve for us to create a system that will fit them.” She is particularly excited about engaging people to serve and to be united, to be able to work together with their passions for service, to be happy together in this way. The materials for the building were donated by people from Asheville, North Carolina, and were deeply appreciated. All over the camps one sees evidence of creative problem-solving, cooperation, and contributions brought from afar. The “donations” building is brimming with winter clothes (for adults and kids), foods of all kinds, and other practical items.

I was particularly interested in the many families that were at the camps, with lots of kids of all ages, including infants. One family from Boulder, Colorado, with 8-year-old Oscar and 11-year-old Audrey, were unpacking their car when I came upon them. Their mother, Susan, said, “We are here to support the protest and to have our kids learn from it. I want my kids to understand that we do what we can to take care of the water and support the indigenous people. To step it up these days we have to hold some ground. This is one of the places we can meet. It would be great if Obama would release the land and kill the pipeline.” Amen.

I encountered a father-son pair from Manhattan. Fourteen-year-old Declan Rexer learned about the encampment from a single segment on MSNBC news but couldn’t find anything else about it in the corporate media. He was particularly upset by the police attacks on elderly protesters. He then went to alternative and social media and found an enormous amount of information. His interest grew and his father, William Rexer, decided to bring him out to North Dakota to learn for himself. They plan to bring back lots of information for Declan’s classmates and to encourage more people to come out to see for themselves. William, a media professional himself, connected with some of the young documentarians at the camp and will provide some material support to them in order to advance their work.

I spoke with Joseph, a Salish man from Montana. I asked him how long he was planning to stay at the camp. He told me, “I’ve been here from the beginning, and I will stay to the end. All winter if that’s what it takes. We have been colonized and divided for five hundred years. This is our time to unite and resist. We must protect our water and our tribes.” He thanked me for coming to Standing Rock and being an ally. He asked me to tell my friends to come out and join the encampment, to be water protectors.

Generosity is evident all over the camp. I particularly love working in the kitchen, a huge army tent with large tables, stoves, and lots of equipment. On each of the two days that I worked in the kitchen there were about a dozen people busily working in happy unison. There was a chief organizer and then four or five people who were in charge of a particular dish, each with one to three assistants. I was an assistant, happy not to have to mastermind anything. The chatter among the workers reminded me of the Park Slope Food Coop squads, where people work together with shared goals. As one man put it, “We come together here with one vision. We are building a new world together.”

While I attend trainings and sacred fire circles, chop veggies, talk with people, drive people around, and walk around the various camps, I am struck by how happy I feel. Sure, this is temporary. Sure, this is not my “real world.” But it is a lovely world, a loving world, a world in which each person is greeted with kindness. Young men and women ride through the camps on horseback, connect to ancient traditions, and bask in the glory of a shared culture of resistance. I do not come from this culture, but I do support their determination, their right to protect their land and water and people, their valiant attempt to build a better world. I am moving slowly and deliberately and thinking about the world we need to build together, but on a much larger scale. Can we decide to be kind to each other, to collaborate, to try to remove ego from our day-to-day practice? I don’t know the answer to these difficult questions. But I do know that when people share a common struggle we can be beautiful. I bask in that beauty at Standing Rock.

Most of my non-service time was spent talking with people, checking out some of the encampments and contingents. Labor for Standing Rock was a small but important such contingent. With flags fluttering and union jackets, shirts, and hats, these unionists were determined to represent the many working-class people, in unions and otherwise, who support Standing Rock. Each of the people I spoke with insisted that the AFL-CIO’s opposition to Standing Rock and support for the pipeline was wrong-headed and dangerous. Peter Parks, a retired longshoreman from Portland, Oregon, said, “The union movement needs to come out in support of the climate movement, it needs to see its interests in common with the world’s people, not just seek out a few jobs for union members.”

Kirk Smith from Terre Haute, Indiana, President of Local 1426 of Workers United, whose factory manufactures plastic overwraps for food and beverages, told me,

I wanted to come here on my own, but my international is supporting Standing Rock so I am representing them. I’m a political activist from a small, conservative town, so I came here to be part of this larger movement. It’s scary how large corporations not even from our own country can get our government to declare eminent domain just for corporate profits and not for the benefit of the people. There is a water source right here; the oil will drain into the water.

He told me that he brought all sorts of supplies from Terre Haute and also went into Bismarck, the nearest sizable town, and bought lots of food to donate. I asked for a message to share and he said, “I expect Trump’s government will have its way with Native Americans as it has for over four hundred years. I hope Obama ends the pipeline now. Greed and power control the world. My union brothers and sisters understand this fight because we are not the elite that benefits.”

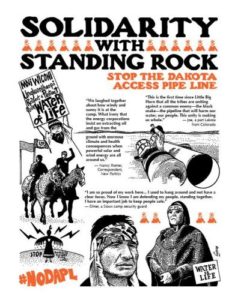

Sitting on lawn chairs at the labor camp, chatting with two other Workers United members, Alex Gillis from Madison, Wisconsin, and Roby from Eau Claire, Wisconsin, we laughed together about how windy and sunny it is at the camp. What irony that the energy corporations insist on extracting oil and gas from the ground with enormous climate and health consequences when powerful solar and wind energy are all around us! Alex said, “We in the working class are beaten up every day. If the working class doesn’t stand up and fight we are doomed. We will go back to the system where we will be serfs. I hate the corporate media, really corporate cheerleaders; they make commercials for the system. It’s important for people like us to tell the true story.”

Carlos Genard, Communications Director of Workers United, Chicago Midwest Regional Joint Board, offers the reasons he is here at Standing Rock:

First, I have Native blood, and I am sick of what the corporations do to Native Americans. Second, I have three children, and if I don’t stand up to ensure pure water for my kids, no one else will. I protect the planet for my kids. Third, there is a disconnect between the leadership of the AFL-CIO and its members. Why does the AFL-CIO stand with the corporations instead of the people? We won’t be able to win unless we have solidarity with Native Americans; we must continue to build the movement.

He also told me that as a dark-skinned Latino, “Standing Rock is the only place on earth where I don’t get racism. No one cares about your color or the way you talk or look. I want to bring my kids here to experience this. My kids go to Chicago Public Schools that have a great union. My daughter’s social studies teacher uses Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States so she’s getting the true story!”

I asked one of the young security guards at the main camp’s welcoming entrance checkpoint for some directions to one of the smaller camps, and he and his comrade insisted on walking me there. They were both in their early twenties and so proud of their roles at the camp. They are both local and are now living at the camp with occasional visits home. Elmer, one of the guards, told me, “I am so proud of my work here. I stand watch at the entrance for over 12 hours a day, and I go around to all the camps, talk with the people, see if there are any problems and if there are ways that security can help.” I tell him that that seems like ideal community policing, something that most law enforcement professionals need to learn about. He tells me that he has found his purpose in the camps. “I used to hang around and not have a clear focus. Now I know I am defending my people, standing together. I have an important job to keep people safe. I couldn’t be happier even though I am so tired.” Our half-hour walk to a nearby camp is filled with personal stories and chatter. These two young, valiant defenders of their people are incredibly open and happy to share with an older white woman from Brooklyn, New York. I am honored.

In the dining tent, during a delicious meal of veggies, beef chili, rice, salad, and fruit, I asked Buffalo Child a few questions. He is a Native elder from Montana and Saskatchewan, mostly Cree and Lakota. I asked him what will happen, what he sees as possible outcomes of the struggle. He sees several different scenarios:

First and most likely, Trump will protect his buddy, Kelsey Lee Warren, CEO of Energy Transfer Partners, as Trump has financial interests in the pipeline. Energy Transfer Partners has been lying and blocking the media since the beginning of the encampment. Second, Trump might push for changing the route of the pipeline, closer to Bismarck, play the hero and then say, “I stopped it and made it go somewhere else.” This might boost his ego. Third, and the worst-case scenario, is that there will be violence against the water protectors and then Obama’s idea that the UN would step in and take over, given the UN’s commitment to the rights of indigenous peoples. We tried to do it the peaceful way, but if there is an attack, the people here won’t fight but other people will rise up all over the country.”

Buffalo Child offered his reason to be at Standing Rock:

I believe in callings, everyone has a calling dictated by conscience and one’s belief system. The consciousness of society is now awake and aware. Standing Rock is my calling. This is a historical movement; it’s never happened before in the United States. This is a “we” event; this is a natural and spiritual movement. We want all people to join our movement.

On Sunday night, November 13, Angela Vivens, one of the tribal elders and lawyers, addressed the hundreds of people at the Sacred Fire, the gathering place where information and culture are shared. She gave us a bit of historical context and present strategy:

The Sioux have more treaties than any other tribe. Over the last 37 years the UN has supported the rights of indigenous peoples, but the United States and Canada were among the very few nations that refused to sign. They finally signed on in 2010.* We have changed our republic from the name “Lakota” to the name “Dakota,” which includes all tribes. We are trying to protect the graves in the burial mounds. We are defending the Fort Laramie Treaties of 1851 and 1868 that acknowledge the 1818 boundaries of the Dakota nation. We have been good Americans, patriots, and veterans. It is now time for us to be good Dakota.

We are owed billions of dollars for stolen land and hydropower. We have reparations due us, called for by the Geneva Conventions. We have no choice but to take back our freedom and land. We have the right to do this according to the Geneva Conventions.

This is a calm before the storm. We need to drum, we need to pray. We are in that thirty-day waiting period [agreed to by the Army Corps of Engineers]. We expect a five-star general and five hundred vets coming here on December 5 to protect the river. Be strong, take care of each other. This silence tells us the permit has been agreed on in thirty days. This will change. We will distribute copies of the treaty and treaty ID and permits for the non-Indians. We are preparing insurance claims against DAPL. We all fought and struggled for unity, and we have to unite the U.S. and Canada nations. We pre-date the state of North Dakota and South Dakota. They stole our name—Dakota.

We are working with the Sami indigenous people of Norway to pressure DNB and Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global [NGPFG], to divest from all corporations connected to DAPL. [DNB is an investment house with 2.8 billion Norwegian krone ($230 million US) in investments advancing the DAPL, and NGPFG has invested over 10 billion krone ($833 million US).] The Sami people are outraged that money from Norwegian workers is being used to deny indigenous rights, spoil the water and land, and contribute to climate change. They are working closely with the [Standing Rock Sioux] Red Owl Collective Legal Team to make this happen.

This is a historical event; it’s never happened before in the United States. Only fools would close their eyes. This is a national and spiritual movement. Come with an open heart and open eyes. Join us!

On November 15, there were two hundred demonstrations and events across the fifty states of the United States in support of Standing Rock. I attended a vibrant and passionate demonstration at Federal Plaza in Manhattan. There were more than two thousand people supporting the water protectors at Standing Rock, demanding that the Dakota Access Pipeline be scrapped—No DAPL. Some of the demonstrators were Native Americans but most of the demonstrators were non-Native climate activists with respect for indigenous rights as well as the rights of Mother Earth.

Perhaps anticipating the nation-wide demonstrations, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers issued a statement on November 14 indicating that it needed more analysis and discussion with the Standing Rock Sioux tribe before a required easement could be granted and thus allow construction of the pipeline to take place under the Missouri River. Energy Transfer Partners management was not happy, but the Water Protectors were glad to have even a brief reprieve.

Organizers of the New York demonstration made it clear that DAPL wasn’t the only pipeline to be defeated. The New York metropolitan area has its own potential tragedy unfolding with the AIM Spectra Pipeline about to be completed that would go under the Hudson River and be routed 105 feet away from the Indian Point Nuclear Power Station—just 10 miles north of New York City. An exploded pipe in either location would be truly disastrous for us. You can plug into that struggle at www.resistaim.com.

So what does all this mean? To me Standing Rock means one of the pathways to resistance: resistance to Trump, resistance to the unleashed power of capital and the corporations destroying our future. It means challenging the passivity that makes Americans so easy to manipulate. It means ramping up our organizing, not just mobilizing; it means deepening our commitment and contact with our local communities and making common cause with our neighbors and allies. It means taking joy from our comrades and neighbors, our friends and our families who participate in these struggles. It means being part of building a new world because we need one so badly.

Note: Names used here may vary from actual names, or omit last names, with permission and per privacy requests.