Sculptor, Painter, and Cartoonist: Laura Gray

The Marxists Internet Archive project recently uploaded the complete run of Labor Action, published by the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, between 1940 and 1958, as well as the Militant, published by the Socialist Workers Party. In the midcentury period these rival leftist newspapers covered many of the same issues, from organized labor and civil rights in the United States to anticolonial struggles around the globe. While the two organizations differed in key respects, their papers overlapped in many ways. From the standpoint of outside observers, at least, the distinction between the two tendencies grew clearer over time, as the WP/ISL moved in the direction of greater heterogeneity, and the SWP became increasingly homogeneous. While the former eventually shattered into a thousand pieces, the latter hardened into a dogmatic sect.

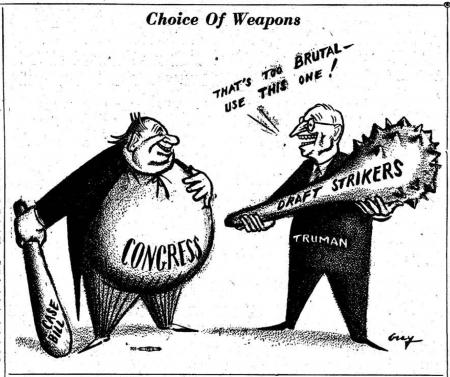

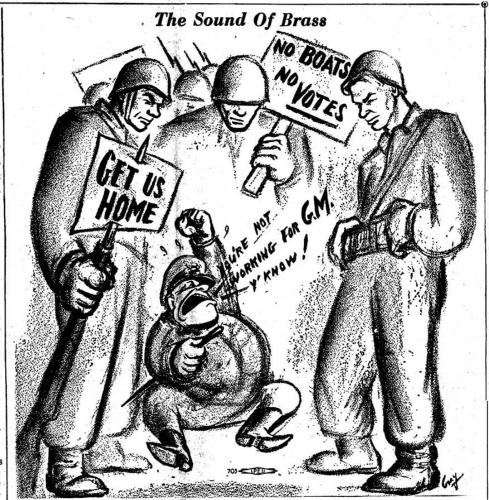

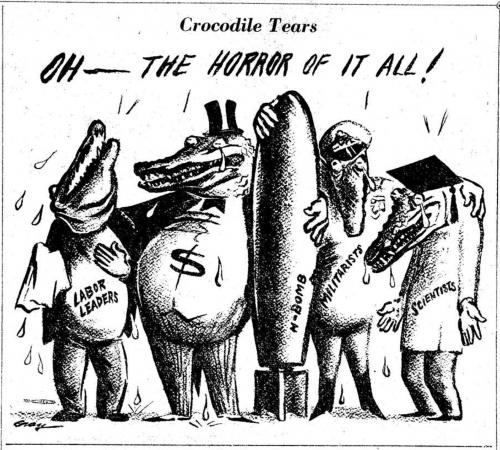

As it happens, Labor Action and the Militant featured the work of two of the country’s best political cartoonists, both of whom were born in 1909. Labor Action regularly published cartoons and caricatures penned by Jesse Cohen, who worked under the name Carlo, while the Militant ran graphics by Laura Slobe, whose party name was Laura Gray. Despite the new wave of public and scholarly interest in the history of comics and cartoons, neither Carlo nor Laura Gray has attracted much attention from historians of the graphic arts. Readers of this magazine might recognize Carlo’s work from the short profile we published in issue 37 (Summer 2004); now it’s Laura Gray’s turn.

Like Jesse Cohen, Laura Slobe attended high school in the 1920s, came of political age during the 1930s, and remained active on the far left after World War II. She was born in Pittsburgh, but grew up in Chicago, where she studied at the Art Institute of Chicago before working for the Works Progress Administration Art Project. As a young, avant-garde artist she concentrated her efforts on painting and sculpture, which remained her lifelong passions. She joined the SWP in 1942, and her first cartoon appeared in the Militant two years later. The labor journalist Art Preis later remembered that, “From the first, her work added such a fresh, bright, satirical note to the paper that it was enthusiastically hailed by our readers everywhere.” According to another SWP writer, “The cartoon’s subject matter was on the agenda of the Militant’s staff meetings. After the staff discussed and decided what the topic would be, Gray would go home and start to draw.” In addition to serving on the staff of the Militant, Gray “worked at a series of jobs to support herself, including painting store mannequins and creating window displays for some of New York’s big department stores.” She remained the SWP’s in-house artist from 1944 until her death in 1958. Tragically, she had contracted tuberculosis in her early twenties, and had a lung removed in 1947. She died after a brief bout with pneumonia.

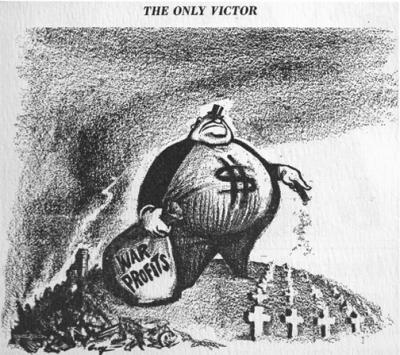

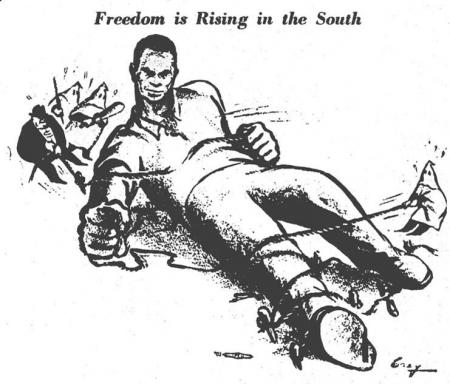

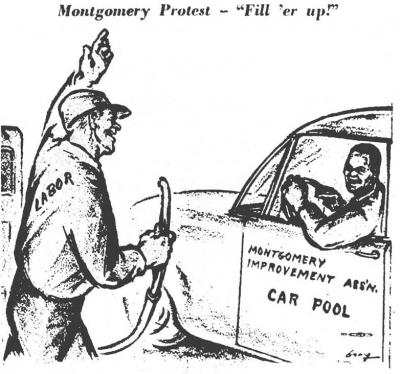

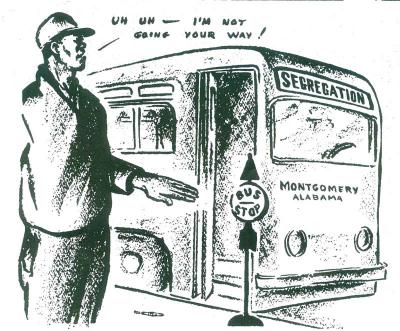

Despite her fragile health, Laura Gray produced hundreds of editorial cartoons, illustrations, and caricatures for the SWP. As far as I can surmise, her work appeared exclusively in the SWP press. In 1987 the party donated 430 of Gray’s original pieces to the Tamiment Library at New York University, where they are still available to researchers. Her work focused on the major issues of the day, from industrial disputes and civil rights protests to the impact of McCarthyism on U.S. politics and culture. According to the SWP journalist Susan LaMont, her work “reflected a style of political art that was popular in the 1930s. The workers were drawn as strong men in work clothes. The capitalists were fat, cigar-chomping men in bankers’ suits, and their wives, diamond-studded and overfed. The Democratic and Republican parties and politicians were depicted as human-like donkeys and elephants — often chewing on cigars themselves — eagerly doing the capitalists’ bidding.”

While Laura Gray’s political graphics took advantage of familiar, well-worn visual tropes, she brought impressive compositional skills to the challenge of encapsulating the party’s line on the issues of the day. While her work was usually indignant, her linework was often quite witty and occasionally light-hearted. She also had a real gift for capturing the facial tics of famous personalities. Her approach was almost certainly inspired by various contributors to The Masses, including Art Young, Robert Minor, and Boardman Robinson, and her published work also suggested the influence of internationally recognized figures such as Kathe Kollwitz, Anton Refregier, and Ben Shahn. She did not start out as an illustrator, and she probably ended up drawing cartoons because that’s what the party needed. As with Carlo, she was an immensely talented artist whose work holds up nicely, despite the passage of time. Readers interested in learning more about Laura Slobe’s life and work should consult the relevant PDFs posted on the Marxists Internet Archive, as well as Alan Wald’s fascinating essay on “Cannonite Bohemians after World War II,” which appeared in Against the Current in July/August 2012.