Reflections of a Student Organizer

Aristotle Wu is the pseudonym of a student organizer with the Gaza solidarity encampments. He was interviewed by New Politics in mid-June.

Aristotle Wu is the pseudonym of a student organizer with the Gaza solidarity encampments. He was interviewed by New Politics in mid-June.

New Politics: Why don’t you begin by introducing yourself?

Aristotle Wu: I am a socialist student and labor activist based in California. I was a participant in one of the University of California Gaza solidarity encampments, but most of my energy was spent coordinating with other comrades engaged in this work––many of them from YDSA [Young Democratic Socialists of America] and some from SJP [Students for Justice in Palestine]––synthesizing experiences, lessons, and challenges, and figuring out how to tackle them together.

NP: How would you characterize the pro-Palestine movement as a whole? How big was it? How deep was it? What was its organization like? Who participated in it?

AW: This movement, I would say, is responsible for the deepest radicalization of young people that I’ve seen in my lifetime. People, including both newly radicalized students and more experienced activists, are developing their ideas, commitments, and skills very rapidly.

Some examples of this are that people who were not already politicized around Palestine have been forced to re-examine the world, prompted especially by the intense repression. They have been compelled to ask why liberal, supposedly democratic institutions, are going to such great lengths to clamp down on free speech and suppress the pro-Palestine movement. From there, it’s a short distance to understanding the material interests that are at play, namely, the Zionist lobby, the imperial interests of the U.S. ruling class, and the involvement of the donors who stand behind each school’s regents or board of trustees.

For more experienced activists, this is the most dynamic and ideologically broad movement a lot of us have participated in. Sure we might have had experience organizing in places like YDSA, SJP, or JVP [Jewish Voice for Peace]. But this is the first movement or context in which all these groups have been brought together. We are working with people from all different sorts of political backgrounds, which makes democracy and collective decision-making extremely challenging, but much more rewarding.

It’s important not to overstate the politicization of this movement. The U.S. student movement is still very much reformulating itself. Some analyses of the movement, and even propaganda from the movement itself, have likened this moment to 1968. It’s true that we are linked to the brave struggles of that year through our solidaristic, anti-imperialist spirit, but in terms of experience, organization, and politicization we are much closer to 1960.

By that I mean, it’s still the case that very few people in society and on our campuses have experience taking collective action. But, at the same time, we have matured compared to the student movement from, say, a decade ago. Over the past eight years there have been significant political transformations in our scene that have equipped people with meaningful organizational experiences to draw upon. For example, the Bernie Sanders presidential campaigns or the mass strikes by educators and healthcare workers at the end of the last decade, Black Lives Matter protests, and student-worker union organizing or labor solidarity work.

While there is a significant repository of organizational experience to draw on, there are a lot of novelties too. Many tactics this movement has deployed are new for this generation of activists, as well as the fact that even if you have labor or electoral organizing experience, those contexts differ in some really important ways from the rhythm and logic of protest movements. The organizing fundamentals may be the same in terms of how we should think about moving people closer to our politics. But the tactics and other aspects are different. For example: student protests don’t have definitive deadlines or election dates; it’s not always clear who your next target should be, what makes sense to raise as an intermediate demand, or who exactly falls into your constituency. Unions, more or less, have a defined membership that does not come with ideological criteria. The student movement, however, is organizing on an ideological basis.

What the novelty of the situation has meant more generally is growing pains around building a democratic movement culture that enables the broadest possible engagement and also ample opportunities for participants to develop into leaders in their own right. Overall, this has been a very new and rewarding organizational experience for people. The most meaningful thing is that this movement has provided us a real context to grapple with how to build a strong movement for Palestine.

To say a little bit about the organization of the movement: this movement seems pretty decentralized at every level—again reflecting the relative inexperience of the student movement. There are so many different organizations participating. And those organizations themselves are decentralized and extremely heterogeneous. For example, some national organizations have very impressive social media accounts with great agitational materials. But I don’t get the sense that those national organizations and accounts are able to influence the political life of groups on the ground.

Groups’ politics also differ by region, and even within the same region people at different levels of the organization have different experiences and orientations. For example, the leadership of a local group could believe in a certain set of politics, but a lot of the people that are joining these groups right now, who are flooding into organizations like SJP, JVP, or PYM [Palestinian Youth Movement], which are seen as the premier organizations of the movement, are very ideologically open, can be politicized in many different directions, and are ready to get involved and make all sorts of contributions. There are a lot of contradictions to grapple with.

The decentralization of the movement has implications for the leadership and the culture of each encampment, which are contingent upon factors like where the encampment is, the organizational ecosystem of the campus, the historical relationships (or lack thereof) between different organizations. The history of student mobilization also shapes the administrative response. For example, the University of California colleges have been a laboratory of administrative counter-organizing given their administrations’ experience with student protest these past few decades. So we’ve witnessed the UCs adopt a more tactful approach compared to many East Coast schools, in my opinion. Many of the encampments are led by local SJP chapters as members of broader divest coalitions with many groups based around Palestinian, Arab, Muslim, or anti-Zionist identity. There is significant variation in their politics depending on the location.

As for the principal goals of the movement, the stated demands of each encampment are pretty uniform. It’s usually some combination of calling on the university administration to end its political and economic support for Israel, demanding an end to the genocide, upholding free speech, and amnesty for students who have been retaliated against for exercising their First Amendment rights. But if we get more fine-grained about it, I think the organizational goals, strategy, and power analysis of each encampment are pretty different, and they are not always shared across the camp, though most camps have achieved some degree of practical unity. The lack of shared analysis and strategy in most camps reflect the lack of opportunities for democratic deliberation and collective decision making. There are factors that make that challenging—namely, security concerns, such as accidentally tipping off the administration and inviting retaliation, which has devastating consequences as we’ve seen. So it’s not like we should condemn these movements because of that. But greater democracy is clearly a necessity for building up a more unified and ultimately powerful movement.

NP: Let’s back up one second. We were talking about the student pro-Palestine movement, but that is in and of itself a subset of the broader pro-Palestine movement, so maybe it would be useful for you to say a few words about how they relate.

AW: Yeah, I’m happy to. As you said, the encampments are a subset of a larger movement. And one thing that’s really great about this movement is that it is self-conscious of that relationship, the fact that students alone cannot carry this movement to its logical conclusion. One dimension of our impact, as the student movement, is that we’ve been able to catalyze other sectors of campus and society into motion. For example, in the University of California system, we’ve seen UAW 4811 take historic strike action around Palestine––in many ways a response to the retaliation against the student encampments that some union members participated in.

There are a lot of tricky questions bound up with the strike, but the major takeaway is that the labor movement has immense structural power that we need to tap into—in higher ed as well as the many other sectors directly implicated in this genocide. The process of revitalizing and politicizing the other sectors will require a longer process of carrying out the rank-and-file strategy. We also need to develop a collective strategy between the labor movement and other social movements and win political representation for these movements. That will take even more work to realize, but it’s important to keep it in mind as a North Star.

As for the politics of the larger movement––of which I think the recent People’s Conference for Palestine in Detroit was a decent microcosm––there is a plurality of beliefs and tactics in the movement. Since October 7, for example, we’ve seen street mobilizations, block-the-boat efforts, boycotts, battles in the media, the uncommitted campaign, student encampments, and direct action targeting individual politicians. Various political differences exist within the movement, but there is also a level of practical unity or openness to the plurality of perspectives. How deep this commitment runs is hard to say. What is clear, however, is that the student movement benefits from the wider pro-Palestine ecosystem and that the success of the student struggle (and any other struggle happening under the banner of Palestine) is ultimately going to be dependent on developing shared goals and an overarching strategy.

NP: What would you say are the strengths of the movement?

AW: This movement seems much more mature compared to previous protest movements, and I think that has a lot to do with the political transformations I cited before, including Black Lives Matter, the Bernie campaigns, the strike waves, and an uptick in labor militancy. In contrast with the dominant politics or tendencies of previous protest movements, the encampment movement has raised clear, communicable demands. Second, it has militant direct-action tactics and fewer examples of ultraleftist acts of desperation, though more of these kinds of actions surfaced as the end of the semester drew near and camps struggled to build strategic unity and a culture of democratic deliberation. I think a further positive is the movement’s instinct to forge relationships with labor and community groups, although the extent to which we’ve been able to do external outreach and coordinate our actions is another question.

Another impressive feature of the movement is how disciplined and clear-eyed people have been around charges of antisemitism. It helps that anti-Zionist Jews are core participants and leaders of many of the camps. The messaging has also been extremely clear and consistent: There is no Jewish liberation without Palestinian liberation. Safety and democracy cannot be secured when there is genocide, ethnic cleansing, and apartheid. Unfortunately, the capitalist media is able to drown out a lot of these perspectives. But the good thing is that the camps are not giving the capitalist media or our opponents a lot of ammo to slander us with.

NP: What would you consider to be some of the weaknesses?

AW: There are a host of challenges. Some, I think, are less the fault of the movement and more a reflection of structural constraints we’re under. For example, left ties to the labor movement have been further decimated under neoliberalism. We’re largely disconnected from the radical traditions of the past, which means we did not inherit as much as we could have by way of mentorship, institutional memory, and the like.

The overarching challenge of the movement, I think, has been the lack of democracy. I think this is less motivated by hardcore sectarianism––although there are some instances of that––than by the need for security. Security concerns are entirely legitimate, but there has to be a better way of dealing with them. This concern around security culture has motivated some to adopt practices like having no open meetings or going by three different code names (which is a security issue in itself). It has also led to a tyranny of structurelessness, autonomous and isolated working groups in many places and a shortage of tactics that help people develop a sense of how the movement is doing and grow their leadership. In the absence of these opportunities, different theories of change proliferate in the camps, and splinter groups escalate without the buy-in of the majority.

There are many obstacles to building an effective democracy, such as people moving in and out of the camps, students joining the movement at different stages, people having to work jobs during voting meetings, and whatnot. But we need to find a way to build this effective democracy, because it is the condition of addressing most other challenges our movement faces.

Another dynamic is that because this is such a new experience –– a lot of us haven’t built occupations before –– we are very consumed by basic organizational questions like, “How do I keep my camp running on a day-to-day basis? Is someone doing the training tomorrow? Do we have enough food? We need new batteries for our megaphone.” At least when we were in the thick of the upsurge, we didn’t have enough time to address larger political questions around strategy and political direction.

As we get more experience building and sustaining occupations it will be really important to begin tackling these issues because our movement hasn’t won a social majority yet. In many cases, the camps didn’t grow much beyond the first couple of days or week. We need to figure out ways to saturate the campus and deal with our opponents. What are the political messaging and tactics that will help us grow? What administrative pushback can we anticipate? How should we deal with that? How much power do we need to win, and how much power do we have right now? How do we escalate on our terms?

We shouldn’t assume that just because the movement is highly visible that people will naturally gravitate toward it and get involved. We’re organizers. We know that some people have to be convinced. Some people might be supportive, but don’t understand why they specifically need to get involved or how to get involved. It’s our job to go meet them, using a mix of creative and traditional tactics like dorm canvassing, class announcements, flyering, tabling, holding events with cultural groups, etc.

Other methodological challenges were also in the mix. As I said before, this is such an ideologically broad movement. Most of us have some experience doing democracy within our own organizations where we talk to people who, more or less, share a political perspective. But all of a sudden, this movement took off, and now we’re in a swamp of organizations. How do you get people on the same page? How do you facilitate effective meetings that are not just hours of people doing vibe checks? How do you work with others with different political backgrounds to develop and socialize a strategy?

Some historical problems that have plagued the left have also plagued this movement: namely, the lack of political representation. We have a handful of individual tribunes for the movement, especially Representative Rashida Tlaib, but they’re not connected to a broader party organization. One implication of that is that our movement is going to be on the defensive, oftentimes fighting Democratic mayors, as opposed to having representatives in the state that are agitating and using their platforms to grow the movement.

On the question of how to relate to the state, there is not much consensus. One contingent believes that we should refrain from engaging because they believe that being associated with politicians is more of a liability than an opportunity and that the contradictions inherent in electoral work are too difficult to surmount. Meanwhile, others come from the Uncommitted voters movement, for example, or believe that Rashida’s platform provides us significant opportunities to broadcast our message and grow our movement. There are various other positions.

Yet another challenge that we’ve faced is how to approach negotiations. And again, this issue, like every other one, is intimately connected to the question of democracy. When administrations say that they’re willing to negotiate, most are not doing so in good faith. Oftentimes, their goal is to back students into a corner, to bring them into back rooms to figure out how to demobilize them, to channel their energy off the streets into the legal realm where things are really confusing and where the administration gets to shape the terms of the discussion.

Of course, we know that the response to administrative maneuvering has to be democratic mass action, keeping up the pressure, and developing a collective strategy, so that when we negotiate with them, we can do it more on our terms instead of theirs. But unfortunately, the infrastructure necessary to win potent concessions and empowering deals isn’t robust enough in many of the encampments.

I know of some examples of open bargaining, namely, at San Francisco State University and some other places, that have been really effective. Historically, open bargaining has been a practice and demand of some of the most powerful (democratic) labor unions. The idea behind open bargaining is that every member of the movement and also the community should be engaged in the bargaining process, not because it’s morally good but because it is strategic for building power. Open bargaining is conducted by (a) allowing people to witness negotiations and (b) crucially, having meetings beforehand to collectively determine negotiating strategy, calling caucus meetings in the middle of negotiations if the administration does something unanticipated or there is a big fork in the road that the movement needs to collectively decide on, and also debriefing after negotiations.

Letting people see negotiations is important not only because seeing the recalcitrance and hypocrisy of the administration is incredibly radicalizing, but also because it puts rank-and-file movement builders in a position to critically reflect on how negotiations are going and how to continue building power. (It’s hard to think of next steps and a better strategy when you don’t have basic info about how the movement is doing and how the administration is responding.)

Having caucus meetings before and during negotiations builds unity between leaders and the ranks about what the strategy is. This is important in at least three ways: (1) Leaders cover their asses because they are acting on a democratic mandate. Right now many camps don’t have this practice, so there is very little clarity about what the non-negotiable demands or red lines are. Sometimes negotiators make blunders or decisions that people think are unacceptable. Disagreements then become personalized and the movement turns on itself as opposed to the administration. (2) When you’re in a closed room with just a few people, it’s easier to feel the pressure of the administration and make rushed decisions. In open bargaining you can read the room, the expressions and sentiments of your comrades. This is a very important corrective. (3) Because the strategy is democratically determined beforehand and everyone is brought in to anticipate administrative maneuvering, the negotiators are empowered to recognize the administration’s moves and they know when to put their foot down and when it might be acceptable to compromise.

Open bargaining, democratically elected leadership, and clear ways to get more involved and have more political ownership over the movement are not very common. To be clear––democracy isn’t a set of rules or tactics. So camps that don’t have these practices are not necessarily virulently anti-democratic. The point is that we need to figure out how to build a democratic movement culture that is informed by security concerns and aware of the different experiences and assumptions that different people and organizations bring to the movement, among other factors. As the old slogan from the labor movement goes, “democracy is power.”

NP: Do you think that at this point the movement has won the message battle with the broader public? We know that the public now supports a ceasefire. But where does the movement stand in the eyes not just of the people on campus but of the public? Or have the Zionist forces succeeded in winning greater support for their political goals?

AW: That’s a good question. I don’t have a definitive answer or much of a data-driven analysis. It is a shame that most institutions built around Jewish identity in American society have thoroughly Zionist politics, and there is little space for anything else. For that reason, as well as the size and reach of the Zionist lobby, I’d be reluctant to say that we’ve come anywhere close to winning the battle of ideas.

But have there been major advancements in the consciousness of ordinary people around Palestine? Totally. Again, it’s hard for me to say because I am so steeped in this movement and the broader left. Mostly what I have is anecdotal evidence. First, it seems extremely difficult for socially conscious, curious college students––at least in certain parts of the country––to avoid sympathetic coverage of the Palestinian struggle, especially on social media. That may not be true of the broader U.S. public. I know of quite a few examples of parents who have voted blue their entire lives, who previously thought that their vote was too precious to waste on a third party or abstaining, but after seeing their kids participating in the camps and getting brutalized by the police, their views have completely changed.

All sorts of people are looking for new frameworks and ideas to help them make sense of what is happening around Palestine. Whether or not they adopt a more anti-Zionist, left perspective is contingent on a couple things, in particular how connected they are to participants in this struggle––whether they be student campers, left political commentators and journalists, or whoever can help them sift through all the conflicting ideas and extract the core historical and political lessons. It’s a matter of organization.

NP: You mentioned that the negotiation of agreements sometimes led to demobilization of the movement, but it seems hard to imagine that the movement wouldn’t demobilize as the school year ended.

AW: Yes, the end of the semester has been a huge hit to our momentum––though in some ways a necessary one since people can’t mobilize forever––and a lot of our interventions have felt like too little too late. During the summer, people have other plans––they’re traveling, working, taking a break––so it puts the kind of consistent and invigorating organizing that is only possible in-person out of our reach. It’s a race against time to make sure that the people who were activated during the encampments don’t scatter to the winds. With the upsurge in the rearview mirror at this point, this next phase of the student movement is largely about consolidating––cohering the most promising committed activists, synthesizing our experiences and lessons from struggle, learning from our mistakes, and preparing to hit the ground running in the fall. The larger pro-Palestine movement that the encampments have been a part of is finding ways to keep up the pressure through the summer as well.

One problem that became clear as the end of semester drew near was the lack of a shared power analysis. We did not know or agree about how much power our movement had, how much power the administration and the state had, and what to do next.

I think one natural instinct was to see the end of semester as a definitive deadline for us to win our demands. So, for a lot of people, the thinking was to escalate and encourage some kind of final confrontation with the administration, even though we didn’t have the forces necessary to win. Many camps had dwindling numbers of people willing to risk arrest. When the cops came, the encampments got swept, people were jailed, and they ended the year demoralized and burnt out.

It’s really important that we develop a sense of our power and what’s necessary to win because this analysis conditions both our long-range strategy and short-term tactics. Is divestment plausibly on the horizon for us? If not, how do we have a strong show of force at the end of the semester that doesn’t compromise our ability to keep growing in the future, especially when things start back up in the fall? How do we create more of a buffer against repression? It’s even more difficult to answer these questions when there aren’t regular, open meetings and different layers of the movement working together to develop a collective strategy.

Many participants have also brought up the need to reconsider our tactics for the fall. The encampment tactic seems exhausted in many people’s eyes, although there are exceptions in some local contexts.

NP: What was the police repression of the movement and why was it so violent? And how did the students react?

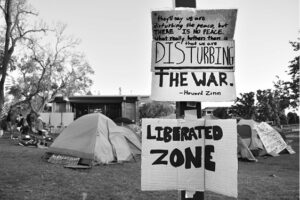

AW: Yes, the repression was intense, disproportionate, heinous, and impossible to construe as anything other than warfare. I can give some examples. Hundreds and hundreds of police, descended on Columbia and City College the night they were simultaneously raided and swept away. At UCLA, a Zionist mob attacked the camp for hours, throwing fireworks at the tents, tearing down barricades, shining lasers in people’s eyes, while the cops stood idly by watching. At Emerson, the university had to call in sanitation workers to hose the blood of students off the walls and floors.

I’ve never seen anything like this before, and what’s even more striking is that students have been completely unwavering and resilient in the face of it. Students have risked their degrees, their jobs, and their futures, and won’t fully recover from the consequences. But the choice to stand up for Gaza, in view of the consequences, was made willingly. This past week we saw Columbia students start the third encampment on their campus despite suffering the most intense crackdown this movement has faced. The enduring conviction and courage of the student movement is immensely inspiring.

In terms of what the repression reveals, it demonstrates what we knew all along. That is, the institutions that are supposedly for us are not actually accountable to us as students, faculty, workers, the general public, or voters. They are accountable to the board of trustees and the broader ruling class. When you look up who sits on these boards of trustees, you find a rogues gallery of super-villains. I was talking with a comrade who pointed out that a lot of repression was being carried out under the auspices of a more diverse ruling class with the backing of Democratic Asian and Black mayors in Boston, Atlanta, and New York City. The ruling class may have a new face, but the violence is the same. It speaks to the absolute bankruptcy of neoliberal identity politics that props up people like Barack Obama as the solution to a crisis. But people are increasingly recognizing that this is a crisis of capitalism, of imperialism.

As for why the repression has been so intense, this is a really important question to ask. We’ve seen divergent responses from administrations. The responses have ranged from negotiations to really hardline repression to radio silence in the hopes that the movement would fizzle out. In some cases, it’s been a blend of these tactics. And one thing I noticed––I could be wrong, this is very impressionistic and anecdotal––is that the violence was initially concentrated on the East Coast. I was reading articles and exposés saying sections of the ruling class coordinated to smother the Columbia camp and make an example out of them. I think that’s true. That’s where the movement first began, and New York City, in many ways, is the political capital of the United States, where so many political disputes and class struggles take place and where the left is most concentrated. So that may contribute to why we saw immense repression there and then.

Other developments are relevant as well. For example, in the California State University—CSU—system, we’ve seen real concrete victories and really potent concessions around divestment––not complete divestment in most cases, but very significant partial divestment––and that raises a lot of questions. I attend a large university system, as some other people do, such as SUNY and CUNY in New York. We haven’t seen campus-level negotiations advance the divestment struggle in the same way they have at the CSU’s. Campus level administration will often say that they are powerless to change the university’s financial practices, which is true in some cases. This allows them to feign sympathy for our struggle and say things like “It’s not my place to decide how our investments work. That’s the statewide board of regents’ job.”

And so it’s really peculiar why we’ve been able to see such advanced victories at a few of the CSU schools. Some camps are very well organized and coordinated with campus labor. But there are probably many political factors at play in addition to the organizational ones that our movement’s rhetoric and messaging centers on. My sneaking suspicion is that these victories are less a reflection of the overwhelming power of students and workers than the distance certain administrations, boards of trustees, and other donors have from the companies we’re targeting for divestment. This is just a hypothesis. Our movement should do more research into this and develop institutional support for corporate research.

NP: Earlier you mentioned the recent Detroit Conference. Tell us a little about that.

AW: Sure. The Palestinian Youth Movement with other groups and sponsors organized the People’s Conference for Palestine, held in Detroit from May 24 to 26. Detroit has a very large Arab and Muslim population and is home to some of the most important Palestinian activists in the country. About 3,500 people attended the conference, including a large contingent from the student encampments.

While I didn’t attend myself, I gathered reports from activists who were there. It was a much-needed gathering that reflected the ideological breadth of the movement. Some participants said that it was not the best forum for strategic debate and discussion. This is not surprising given that our opponents were definitely there listening in. Plus, it was the first gathering of its kind, with so many different activists, priorities, and experiences to juggle. It’s hard to organize an experience that leaves people feeling the unity, as opposed to the disunity of the movement. If this conference was not the most conducive to debate and discussion, hopefully it has created a foothold for these things in the future. And in many respects, it has. Participants were able to connect with other comrades who they can reach out to strategize and work with after the conference.

Because the conference had such an ideologically diverse audience (the composition of the conference leadership and planners being less clear to me), there were a lot of perceived differences, as you would expect. Some people noted a very strong Islamist current that they themselves might not have agreed with. There were also, as I said before, very different instincts around electoral politics. One concrete initiative emerging out of this conference is a campaign against Maersk, the Danish shipping company.

NP: Where do you see the movement going, and what would be your recommendations? What strategy do you recommend for the future?

AW: Well, the campus upsurge is largely over. It is over for most people, except for maybe one or two holdouts where the college uses the quarter system and thus the semester is still going on and people are in finals right now. So the phase of the movement we’re in is different from what it was before. It’s not about building these occupations anymore. It’s about consolidating the gains of the upsurge––making sure that the activists we met through this process stick with it, processing our experiences and developing a shared sense of which lessons to take away, committing those lessons to institutional memory, and preparing for the next upsurge.

It’s hard to say what will come next because the movement is so decentralized. But I think that there’s a good appetite to continue organizing in the fall, and that the form the organizing takes will vary much more from school to school as compared with the uniformity of tactics we saw this past semester. Earlier I mentioned various challenges that were common to most of the camps. I think it’s important to start tackling those questions before we start prefiguring a strategy.

NP: It seems that Biden is desperate to get a ceasefire before the election, and maybe before the convention. To be sure, the ceasefire will not be a solution that we think is adequate. But if there is some sort of ceasefire in place in September, what impact do you see that having on the resurgence or diminishing of the activism?

AW: My sense is that virtually everyone in the movement believes we need to go far beyond a ceasefire. But the broader layer of people watching us and those who are newly radicalizing might not be on the same page. Our movement hasn’t formally discussed what to do. I’m sure different organizations and groups of activists have considered what to do next, but on the whole, there is no consensus around what the next demand should be, which slogans to advance, and which tactics to deploy. It’s important that we create more opportunities in, as well as between, organizations to discuss these questions, so that we’re not caught off guard and can make the case to people that more is necessary, and we have an inspiring plan to grow. Otherwise, the momentum will decrease or be channeled in a million different directions.