Race and Counterrevolution [1]

Optimism is the prozac of the sociological imagination. Indeed, several of sociology’s founders were disaffected children of Baptist ministers who substituted millenarian ideals with the secular version of a heaven on earth. The men of the Chicago school conceived of sociology as a secular eschatology that would be an instrument of social amelioration. What’s wrong with that, you might be thinking? Nothing at all — except when it leads to a false optimism where we look upon the world through rose-tinted glasses. Where we are mesmerized with what might be, and turn a blind eye to what is. Where we extol "progress" but evade its antithesis: entrenched systems of domination and oppression. Or we forget Piven & Cloward’s admonition that power only concedes as much as necessary to appease and to co-opt, and then retracts these concessions as soon as it is politically safe to do so. Finally, there is the dialectic of history — that revolutionary change sets the stage for backlash and retrogression, as the champions of the old order retrench and rally forth, often with revanchist fervor.

In racial matters, the tendency in sociological discourse has been to acknowledge the iniquity of the moment, but to take comfort in the fact that things are better than in times past. Thus, Jim Crow was bad, but at least blacks were not slaves. Or racial inequalities are deep and persistent, but at least blacks are not sitting in the back of the bus. Or affirmative action is dead, but we got Obama in the White House. By this logic, the nadir for blacks was Middle Passage, and things have been getting better ever since! But to paraphrase James Baldwin: it is wrong to use the crimes of the past to justify the crimes of the present.

Albion Small, the founder of the Chicago School of Sociology, once wrote, "There is a pot of gold at the end of the sociological rainbow." Indeed, the assimilation model, which was at the center of sociology’s master paradigm, was predicated on an evolutionary optimism whereby the nation’s constituent races would ultimately be incorporated into the body politic. A reassuring narrative, to be sure, and to cut Robert Park some slack, his precepts about assimilation were meant to counter nativist fears that "the new immigrants" from southern and eastern Europe were unassimilable. However, when it came to the dark races, assimilation theory had a perverse subtext. As R.W. Connell and Charles Mills have argued, assimilation theory embodied the logic of imperialism.[2] Only in its obfuscating terminology was sociology’s pet theory different from the standard defense of colonialism, that it spread civilization as the "backward races" were assimilated into the cultures — and through miscegenation — the germplasm of more "advanced races."

Optimistic teleology is not a problem only of mainstream sociology, but pervades Left thinking as well. In its master narrative, capitalism propagates the seeds of its own destruction, and oppressed groups develop a revolutionary consciousness, rise up in protest, and ultimately install a new and more just order. Unlike mainstream sociology, at least Marxists had a paradigm for grasping the nature and causes of black insurgency when it erupted in the Deep South in the late 50s and 60s. However, some leftists — Ralph Bunche, for example — pooh-poohed the civil rights revolution because it did not address the underlying political economy that lay at the root of racial hierarchy. Clearly, Bunche was wrong — the civil rights movement was a necessary stage in the black liberation project. But Bunche has also been vindicated by history. As important as they were, the Civil Rights Laws of 1964 and 65 were a reformist agenda that did not fundamentally alter the political economy that engenders and reproduces racial hierarchies. Remember, too, that these laws only restored rights that were presumably secured a century earlier by the Reconstruction Amendments and the Civil Rights Act of 1866. If this is "progress," it is the progress of a people on a historical treadmill.

As with the first Reconstruction, we were given "bricks without straw" (to invoke the title of Albion Tourgée’s 1880 novel).[3] Civil rights legislation was not backed up with programs of genuine reconstruction to redress the deep inequalities that are the legacy of slavery. And as with the first Reconstruction, it was only a matter of time before the enemies of the civil rights revolution mobilized a counterattack. I submit that we are in the throes of a counterrevolution that has systematically whittled away most of the gains of the post-civil rights era. With ruthless determination, and with indispensable backing from conservative foundations, the Federalist Society hijacked the judiciary system from the bottom to the top (the Left could take a lesson from this feat of organizing from the bottom up). And once it had a conservative majority in the Supreme Court, through a series of rulings this counterrevolution has pounded every last nail into the coffin of the civil rights revolution. Not only are we witnessing a rollback of minority rights, but race and racism have been cynically exploited to buttress and reinvigorate the political Right, and to mobilize white voters behind a reactionary social agenda.

This began with a crusade against welfare and affirmative action — both entwined with race. But these were only dress rehearsals for a wider attack on the social welfare programs of the New Deal. And today, under the mantra of "states rights" — which was the battle cry of slavery and succession and lay at the heart of Plessy v Ferguson — we see an even more far-reaching challenge to ripping up the social contract that was the legacy of the New Deal and the Great Society. We are left to wonder with Lorraine Hansberry who really won the Civil War.

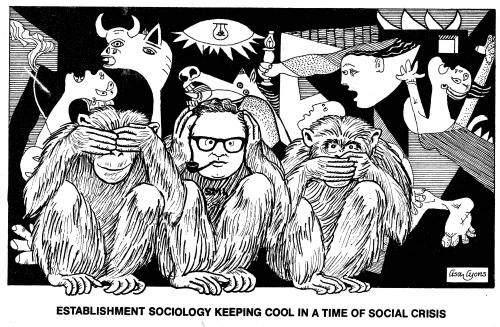

In Black Reconstruction, Du Bois wrote: "The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery." My contention is that we are witnessing a similar retrogression in the wake of the Second Reconstruction. Blacks are no longer in the back of the bus—indeed we’re in the White House!—but this has been manipulated, not to advance the cause of racial justice, but on the contrary, to camouflage the dismantling of affirmative action and antiracism policies generally. In 1963 Everett Hughes famously used his presidential address at the American Sociological Association to bemoan sociology’s failure to predict the civil rights revolution. There is maddening irony in the spectacle of social scientists gathering to contemplate "real utopias" or a postracial future at a time when we are witnessing the dismantling of the Second Reconstruction. Which is to say, when we are moving "back again toward slavery."

What better example of counterrevolution than the passage of Voter ID laws that are nothing more than an incarnation of the poll tax and the grandfather clause — race neutral on their face but patently racist both in their intent and their impact. According to the Brennan Center, these laws will effectively disfranchise as many as 5 million voters, disproportionately black and Latino.[4] Add to this another 6 million impacted by restrictions on felon’s voting rights.[5] So disfranchisement is back. And that’s not all. Convict labor is back, implicating major corporations who have found a reserve army of cheap labor in the prison industrial complex.[6] Back, too, are vagrancy laws in new guise. In New York City, that famed citadel of tolerance, last year there were nearly 800,000 stop-and-frisk searches, 87 percent involving blacks or Latinos.[7] Indeed, so is lynching. What else was the Trayvon Martin case if not Emmett Till all over again—an official license and cover-up for killing a young black man who crossed the color line?

The seeds of counterrevolution were planted even before the passage of the 1964 and 1965 Civil Rights Laws, and came to early fruition in the 1968 election when Humphrey won only 10 percent of the white Southern vote. (Obama won 20 percent of the white vote in the Deep South, a grim measure of "progress.") As social scientists say in their prosaic fashion, this marked the beginning of "a political realignment," as the "Solid South" turned solidly Republican. But let’s be clear at what is involved here: "Negroes" were granted elementary rights of citizenship, and within a decade the entire South seceded from the Democratic Party! What was even more ominous was George Wallace’s unexpected traction with white voters in the urban North. The handwriting was on the wall: as Thomas Edsall and Mary Edsall wrote in Chain Reaction, the Republican Party would emerge as the party of segregation.[8]

The 1968 election also marked the beginning of the loss of white voters to the Democratic Party in northern industrial states. Nixon wasted no time in rewarding his new electoral base: he nominated two outright segregationists to the Supreme Court, and although they were rejected in the Senate, this was unmistakable proof that the counterrevolution was in full swing. White supremacy was back. And thanks to the Federalist Society, future Jim Crow judges would be dressed in respectable judicial garb.

Thus, we are in the throes of a counterrevolution that aims to drive every last nail in the coffin of the civil rights movement. It is important to acknowledge the role that affirmative action played in spawning this counterrevolution, not only because it stoked white resentment, but also because it provided a rhetorical makeover for Conservatives who could now shed the image of being racist and anti-Semitic, and presented themselves as champions of the rights of the white working class.[9]

Affirmative action was by far the most important policy initiative of the post-civil rights era. It drove a wedge into the wall of occupational apartheid that had existed since slavery. And it achieved its prime policy objective by opening up avenues of opportunity — not only in the corporate world and the professions, but in major blue-collar industries as well. Without affirmative action, we would not have the black middle class as we know it, including the two people who occupy the White House.

Affirmative action had its origins in the Philadelphia Plan, which sought to desegregate lily-white unions in Philadelphia’s construction trades. The Plan was originally drafted in Johnson’s Department of Labor and shelved after Humphrey’s defeat. In 1969 the Plan was disinterred by Arthur Fletcher, the black Assistant Secretary of Labor, who has rightly claimed to be "the father of affirmative action." But the other progenitors are Charles Shultz, Fletcher’s boss, John Mitchell who successfully defended the challenge to the Philadelphia Plan in the Supreme Court, and Nixon himself, who not only gave the Plan his indispensable backing, but also risked a great deal of political capital in heading off an attempt in Congress to kill the Plan.

There has been much speculation as to why Nixon, who won the 1968 election with his "southern strategy" and who nominated two segregationists to the Supreme Court, would give such resolute backing to the Philadelphia Plan. The prevailing view, which was held by Bayard Rustin (who was in the throes of his own regression "from protest to politics") was that the Plan was Nixon’s perverse attempt to fragment the liberal coalition between blacks, labor, and liberals (read: Jewish liberals). I think there is a more convincing explanation for this apparent contradiction. Nixon found himself in the interstices of the shift from revolution to counterrevolution. This explains why he oscillated between appointing segregationist judges, on the one hand, to proposing liberal policies like Moynihan’s Family Assistance Plan that guaranteed a family wage (which horrified conservatives helped defeat in Congress), and appointing George Romney to head the Department of Housing and Urban Development (Romney was eased out of office after his plan to desegregate the suburbs evoked a furious backlash).[10] In the case of the Philadelphia Plan, Nixon sought to appease headline-grabbing protests by grassroots activists at construction sites in cities like Chicago, Detroit, and New York. At first it seemed as if he had nothing to lose by sticking it to Democratic unions, but when affirmative action was implemented and galvanized widespread protest, Nixon went into reverse gear and revoked the very "quotas" he had put into place.

However, the genie was out of the bottle and once affirmative action passed Constitutional muster in the federal courts, it was extended to all government contractors, including universities. This aroused widespread resistance, and the professoriate responded with what they do best: erudite studies that provided the anti-affirmative action forces with intellectual legitimacy. By the mid-eighties, after Reagan had appointed O’Connor, Scalia, and Kennedy to the Supreme Court, and had elevated Rehnquist to Chief Justice, the new conservative majority wasted no time in reversing Court rulings of only nine years earlier. So much for stare decisus. The end result is that affirmative action has been eviscerated by a series of Court rulings, and pending the mercurial vote of Justice Kennedy, the upcoming case of Fisher v the University of Texas is poised to drive the last nail in the coffin of affirmative action.

Indeed, the three pillars of antiracist policy — school desegregation, affirmative action, and racial districting—have all been eviscerated or gutted altogether. This was the ignominious achievement of the conservative majority on the Supreme Court who cynically cloaked their rulings in the 14th amendment, refusing to acknowledge the difference between racist practices driven by racial animus and the use of race to remedy those very injustices. Like the First Reconstruction, we are left with "bricks without straw," which is to say, with empty rhetoric and false promises. The gutting of affirmative action is particularly calamitous, in that it will slowly erode the social-class gains that blacks made during the post-civil rights era. We are left with the specter of blacks walking briefly in the sun and moving "back again toward slavery." Not despite Obama, but arguably with his help, and not only his silence and acquiescence, but often with active complicity. For example, his "race to the top" uses the false promise of "education" as rhetorical cover for his failure to address the economic crisis that besets black communities, at the same time that it abets the reactionary crusade for school privatization and disinvestment in public education.

Counterrevolution is built on the fragments and shards of revolution.[11] The losers — the beneficiaries of white supremacy — do not fade quietly into the penumbra of history, but they retrench and mobilize to restore their power and privilege. After the Civil War, it took only 28 years from the passage of the 14th Amendment to Plessy v. Ferguson, which passed in a 7-1 decision. Affirmative action was enacted as policy in the 70s and rescinded by Court decisions in the mid-80s. Note that in both cases counterrevolution was enacted by the Supreme Court, reflecting a political realignment fueled by racial backlash.

Let me close with a brief comment about Obama. The first thing that needs to be said is that his election provided stark proof of why blacks were disfranchised through virtually all of American history. Obama owes his election and reelection to the unprecedented turnout of blacks, and the fact that the two-thirds of Latinos who voted for Hillary Clinton in the 2008 primaries, voted for Obama in the 2008 (this number increased to 71 percent in 2012). One figure speaks tons: 89 percent of Romney votes came from white non-hispanics. Put another way, in 2008 57 percent of whites voted for McCain; in 2012, the percentage voting for Romney actually increased from 55 to 59 percent. In other words, if only whites had voted, McCain and Romney would each have been elected by a landslide. This explains why Republicans have resorted to voter suppression (effectively restoring the three-fifths principle in the Constitution whereby southern states could count slaves as three-fifths a person for purposes of apportionment in Congress and representation in the Electoral College). It also explains why racial undercurrents and coded racism abounded in the campaign discourse. This was on full display when Romney used his appearance before the NAACP to proclaim his opposition to Obamacare and signal to his white supporters that "the rights revolution" was dead.

With Obama in the White House, Republicans can have it both ways. They shamelessly tap the reservoir of racism to discredit Obama, to deride national health insurance as "Obamacare," tagging any social welfare policy as stealth reparations for blacks who exist as freeloaders on the public treasure, and now to unconscionably transgress democratic principle by restoring Jim Crow subterfuges to suppress black voting rights. At the same time, Republicans reap the advantage of having a President who puts a black face on neoliberalism at home and imperialism abroad. To borrow a nugget from Malcolm X: we’ve been snookered, first of all by our own false optimism and utopian reverie.

Footnotes

1. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 Meetings of the American Sociological Association.

2. R.W. Connell, "Why Is Classical Theory Classical," American Journal of Sociology 102 (May 1997): 1511-57 and Charles W. Mills, The Racial Contract (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997).

3. In her introduction to a recent edition of Tourgee’s Bricks Without Straw, Carolyn Karcher writes: "Grimly chronicling the ‘counterrevolution’ that so swiftly eliminated the rights the freedpeople had won with the help of their white supporters, he excoriates the northern public for succumbing so credulously to the white supremacist propaganda campaign against Reconstruction. In the process, he articulates insights as relevant to the present as to the past."

4. Not Again! How Our Voting System Is Ripe For Theft and Meltdown in 2012.

5. Michele Alexander, The New Jim Crow (New York: The New Press, 2012).

6. Prison labor on the rise in US.

7. ‘The Scars of Stop-and-Frisk’.

8. Thomas Byrne Edsall and Mary D. Edsall, Chain Reaction: The Impact of Race, Rights, and Taxes on American Politics (New York: Norton, 1992): 62.

9. Nancy MacLean, Freedom Is Not Enough (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2006): Chapters 6 & 7.

10. In The Pursuit of Fairness: A History of Affirmative Action (New York: Oxford, 2004), Terry Anderson writes (p. 119): "Promoting affirmative action was another demonstration that the president flirted with liberalism during his first two years on office."

11. For a penetrating analysis of the concept of counterrevolution, see Stephen Eric Bronner, "Notes on the Counter-Revolution," Logos , vol. 10:1 (2011).