On SNCC’s 60th Anniversary

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee began as an organization of students from black colleges in the South to integrate lunch counters that refused service to blacks. The tactic they used was the nonviolent direct action sit-in. What began with a handful of students in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, sixty years ago, became a mass movement. This is the story of how SNCC changed from a mass reform movement to a revolutionary Black Power cadre organization. It was destroyed by a combination of strategic errors and miscalculations, internal discord, external repression, and, indirectly, by its own successes.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee began as an organization of students from black colleges in the South to integrate lunch counters that refused service to blacks. The tactic they used was the nonviolent direct action sit-in. What began with a handful of students in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, sixty years ago, became a mass movement. This is the story of how SNCC changed from a mass reform movement to a revolutionary Black Power cadre organization. It was destroyed by a combination of strategic errors and miscalculations, internal discord, external repression, and, indirectly, by its own successes.

In a period of 60 days the sit-ins spread to nearly 80 communities from Ohio to Florida. By March 1961 some 138 municipalities and businesses had desegregated at least some facilities, often despite intense hostility and brutal attacks by local whites. Nearly 1,000 blacks and white sympathizers were arrested in February and March 1960 alone. Hundreds of students suffered tear gas, police dogs, and beatings. Dozens were expelled or suspended from their schools. But very significant progress in changing segregationist patterns in restaurants, public libraries, swimming pools, and even churches were made in just a few years.

In spring 1961 an allied organization, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), organized “Freedom Rides” to challenge segregation in interstate busing. Two SNCC members, including future SNCC chair John Lewis, were part of the integrated group that rode the buses (which were attacked by mobs, with one bus burned). This would eventually lead to an Interstate Commerce Commission ruling barring segregated facilities in bus and train terminals, although enforcement was sporadic.

SNCC’s activities in voter registration campaigns, especially as the leading edge of “Freedom Summer” in 1964 and in the formation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) and the Lowndes County (Alabama) Freedom Organization, led to increasingly effective black political participation and the gaining of political offices in parts of the South where there had been no black officials since the Reconstruction Period (1867-1877). Julian Bond’s campaign for the Georgia House of Representatives, for example, promoted social issues such as increasing the minimum wage and even abolishing the death penalty that were far in advance of the national Democratic Party. SNCC helped to organize the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union, with several thousand members, mainly among day laborers in cotton fields. The MFLU advocated a number of progressive reforms including equality in wages and job opportunities for black and white workers. SNCC was involved in the campaign for “home rule” in Washington DC, which was then directly under the rule of the U.S. Congress and had no independent political power. (A SNCC veteran, Marion Barry, later became mayor.) SNCC supported and worked for numerous black candidates for public office including the U.S. Congress, in Georgia, Alabama, Virginia, and North Carolina. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, promoted by President Johnson, would not have been possible without SNCC, although of course other civil rights organizations such as CORE and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) were also involved.

However, as Cleveland Sellers of SNCC puts it, “When the federal government passed bills that supposedly supported Black voting and outlawed segregation, SNCC lost the initiative in those areas.” A number of SNCC workers had trouble adjusting to roles in various anti-poverty programs. “They sneered at professional reformers who worked regular hours and submitted to organizational restraints.” In November 1965, some of the more pragmatically oriented SNCC workers left to work with the MFDP, which others saw as in danger of taking on the very values of the political system it was designed to change. But SNCC’s own organizing efforts were lagging and failing to produce clear benefits to blacks in both the North and South. Supporters, including financial ones, were drifting away. Differences between SNCC and the SCLC, a more church-based group closely associated with Martin Luther King Jr., grew after the Selma, Alabama, demonstrations for voting rights. One activist wrote, “By the close of 1965, the compounded conflicts … had reached the point of no return: Communication between various elements of the movement had become virtually nonexistent, diminishing contributions, and widening schisms between North and South, black and white, poor and not poor, took their final toll.”

SNCC faced some strategic decisions at the height of its strength, following the Freedom Summer voter registration campaign in Mississippi. It had at that time a large cadre of organizers, many followers, and a reputation for courage and determination. SNCC might have chosen to continue to work through political avenues such as electoral politics and disciplined nonviolent demonstrations. No one forced SNCC to move in a direction that would inevitably lead to clashes with the state that it was bound to lose. No one forced SNCC to replace the “Freedom Now” slogan with “Black Power” in June 1966, during the march supporting James Meredith’s solo march for voting rights (he was wounded by a sniper on his first day out). It was at this point that John Lewis and other advocates of nonviolence began to distance themselves from SNCC, and when liberal and mainstream civil rights organizational financial support began to dry up.

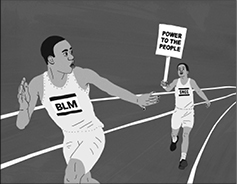

Daniel Del Toro has worked on award winning mobile activations for Black Lives Matter and is a new illustrator with a focus on making political art. His portfolio: BabyMakingTeam.com/Art

But could SNCC really have gone a more conventional route, thus avoiding repression and perhaps again becoming a major factor in civil rights and American politics more generally? Many of its staff and its followers, after abandoning SNCC, did continue the fight for equal rights through participation in the Democratic Party and in mainstream civil rights organizations. Julian Bond was later elected to three terms as president of the NAACP. On the other hand, SNCC’s experience of conventional politics, of step-by-step reform, of attempts to work within the Democratic Party (as when it tried to have the MFDP seated at the Democratic Party National Convention in Atlantic City in 1964), led many SNCC workers to conclude that traditional ways (including the nonviolent and religious-based strategy of King and the SCLC) led nowhere, or at best to gains so minimal that they could be considered little more than trickery. The conditions of everyday life, especially for the many black poor, were still too desperate for many in SNCC to accept “crumbs.” Voting did little to change this. Nor can it be argued, given the evidence, that the government would have left SNCC alone even if it had gone a more “respectable” route; all the mainstream civil rights organizations were not only under surveillance, but, as in Martin Luther King’s case, the victims of government-planted rumors intended to disrupt completely legal activities. The FBI under J. Edgar Hoover made little distinction between respectable and revolutionary black activists.

After 1964, SNCC, rather than following any sort of thought-out political strategy to cope with new conditions, seemed to lurch forward step by step, with each step of its apparent choosing closing off alliances and financial support, leading to further isolation. If it had a strategy it was to mistake state repression for a sign of weakness on the part of the power structure. It failed to see that repression together with its partner, cooptation, indicated strength even as the American war in Vietnam intensified and peace forces against the war grew more militant. In this SNCC was not alone. The Black Panther Party, as well as segments of Students for a Democratic Society and other New Left groups, also made this mistake. For a few older observers on the left this did not come as a surprise. It would have been difficult for the relatively theoretically naive members of SNCC (some of whom rejected most theory, especially Marxism, as “white”) to have clearly understood that state repression was at that moment a sign of state strength and not weakness, that the revolution was not around the corner. But SNCC only slowly came to understand that repression as carried out by the state via local police and the FBI was undergirded by a “well-organized white conservative backlash against black activism,” in particular against advocates of Black Power. SNCC workers “refused to soften the tone of their rhetoric even while recognizing that outspoken militancy often unified whites in support of police repression while dividing blacks.”

Bob Zellner, a white Southern former SNCC activist, summarizes the dilemma.SNCC began by working with three important and effective tools. One was nonviolent direct action, religiously motivated, superbly suited for public relations (outside the South and throughout the entire observant world), and effective in changing “race relations” in upper southern states in significant ways, if not completely. The second, also important in public relations and fundraising, was its interracial composition. The third was its commitment to long-term community organizing and the training of local leaders. The first was displaced with an acceptance, initially only informally, but finally with full commitment, of armed defense. The second was finally abandoned in December 1966 with the expulsion of white SNCC staffers. The third, grass-roots organizing, was gradually whittled away by the “defection” of SNCC workers to anti-poverty programs and Democratic Party political activity. As more and more SNCC workers abandoned the organization to take the route of working in reform campaigns, the remaining militants felt increasingly isolated, yet were left more convinced than ever that the revolutionary road was correct. But that rhetoric led even further to the abandonment of SNCC by liberal and mainstream civil rights organizations.

Contributing to this abandonment, Zellner argues, were two radical decisions that many, perhaps most, liberals could not countenance at that time: SNCC was the first civil rights organization actively to oppose the American war in Vietnam, even to the point of advocating draft resistance. Martin Luther King came out against the war later and also suffered the loss of support of many liberal and labor allies as a result. And many Jewish supporters turned away because of SNCC’s publishing an article supporting Palestinians’ right to self-determination even though this was not an official position.Three issues, the expulsion of whites, Vietnam, and Palestine, Zellner argues, “together spelled the eventual doom of the organization.”

Yet SNCC’s sympathies with the Palestinian people should not have come as a surprise since by 1967 SNCC had become, in its own view, part of the worldwide anti-imperialist cause. As James Forman, one of SNCC’s most perceptive leaders, saw it later, “[f]or SNCC to see the struggle against racism, capitalism, and imperialism as being indivisible made it inevitable for SNCC to take a position against the greatest imperialist power in the Middle East, and in favor of liberation and dignity for the Arab people.” Compromise on this issue would have been considered a betrayal of the anti-imperialist cause.

The effects of repression, in the view not only of movement participants but also of almost all observers, cannot be underestimated when considering SNCC’s gradual demise. As Lewis Killian—a white sociologist of Southern background long involved with civil rights activities—observed in 1975, insurgency “has subsided not because the racial crisis has passed but because white power has demonstrated that open black defiance is extremely dangerous and often suicidal. The ranks of the most dramatically defiant black leaders were decimated by imprisonment, emigration, and assassination.” Surely this contributed to “battle fatigue” and to the exhaustion of older members (and the lack of a cohort of younger militants to replace them). One student of SNCC found that the time of participation in SNCC by the average worker was “no more than one year.” Although this is hard to believe, it is true that membership declined dramatically after 1966.

The Black Panther Party suffered the most extreme example of this repression. By the time the party was founded in late 1966 SNCC was already on its downward trajectory. In 1970, the very year it suffered the most repression, the BPP had offices in 68 cities, but it too had begun to decline. Unlike SNCC, the party, with its roots in California and in northern urban locations, was not the victim of mobs or vigilante organizations such as the KKK. Instead the agent of repression was the state, from local police to the FBI’s Cointelpro project (which also targeted SNCC). Advocacy for armed defense was the party’s original reason for existence, which undoubtedly created more angst within the “law-and-order community,” but SNCC had also come to share that strategy. Both organizations suffered from infighting but the Panthers’ internal battles were more severe and more violent.

It is fair to say that SNCC’s legacy is a proud one. Many of SNCC’s veterans have gone on to important public-service careers, including an ambassadorship to the UN and seats in Congress. Their survivors compose a significant sector of a civil rights veterans website, reunions are frequent, and deaths are publicized and mourned. The Panthers, meanwhile, have become mythologized as heroic martyrs, but those stories have been increasingly contested over the years. Farber details the party’s “promising beginnings,” but cites autobiographies of some of their former leaders and members, describing “an organization that mixed its political actions with a great deal of victimizing criminal activity … with a high quotient of bullying and outright gangster behavior.” By 1971 the BPP leadership was split between those advocating community-based reforms such as breakfast programs and an armed self-defense faction that accused the former of opportunism. Many Panthers still “wanted to stand up to the police. … But the boundaries between revolutionary action, adventurism, and criminal activity were not always clear.” Meanwhile, government-sponsored breakfast programs grew rapidly as part of President Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” undercutting the Panthers’ appeal.

Did the class composition of the Panthers contribute to its dismaying demise? Farber makes a convincing case that the Panthers’ base, disproportionally drawn from an urban “lumpenproletariat” of (mostly) men outside the labor force and including ex-cons led almost inevitably to an “authoritarian internal structure” and later to a “relationship to the criminal underworld.” The class base of SNCC’s workers was distinctly different. Most of the activists came from stable working-class and middle-class, often religious, backgrounds.

How much did the slogan of Black Power and more generally the rhetoric of black nationalism (not only by SNCC) contribute to the defection of liberal organizations and to the “white backlash” that led to the victory of the Republican Party in 1968 and subsequent years? (It should be noted that the Panthers did not use anti-white black nationalist rhetoric and did have financial support from liberals until the Panthers’ thuggish behavior finally turned off the faucets.) Countryman argues that Black Power as it was carried out in practice (and in Carmichael’s original meaning) succeeded in constructing “a vital and effective social movement that remade the political and cultural landscape of American cities during the late 1960s and 1970s in ways that postwar liberalism could not and did not accomplish,” by mobilizing the black vote and electing black politicians. But this strategy failed to accomplish major changes in the living and working conditions of many if not most black families because of “urban deindustrialization and of suburban anti-tax politics.” That anti-tax sentiment was itself a component of white backlash against the rather minimal welfare state of the Johnson era, which many whites saw as benefiting the “undeserving” welfare-receiving (and mostly black, in the white public’s incorrect perception) poor.

Daniel Del Toro

In fact the skin color of mayors and other public officials did not matter. They were (and are) constrained in their ability to create change, just as their liberal reformist white predecessors had been. In this context neither the conventional civil rights organizations nor the more militant groups such as SNCC and CORE could be effective. Black urban politics had little relevance to the fight for significant social change, and this surely affected low voter turnouts at least until the Obama era.

Did SNCC fail? In the 1970s, with black nationalism still on the rise, many black university students dismissed the nonviolent integrationist movement, including SNCC (by then gone from the scene) and Martin Luther King (also gone), as having been irrelevant to the long-term goal of full equality, not to mention liberation as a people or nation. The Panthers’ revolutionary rhetoric seemed an attractive alternative to some. But this view is surely simplistic. On a day-to-day level, by 1970 the South was a vastly different place compared to just ten and certainly twenty years before. “In the South,” as Piven and Cloward said in 1977, “the deepest meaning of the winning of democratic rights is that the historical primacy of terror as a means of social control has been substantially diminished. The reduction of terror in the everyday life of a people is always in itself an important gain.” This diminishment of terror went hand in hand with the undermining of segregation in many dimensions of public life. “The South,” noted Aldon Morris, a black sociologist, “is a different place today. …Southern blacks now live in a world … that does not automatically strip them of human dignity.” SNCC was central to this progressive development.

With the election of Barack Obama it was hoped by many that he would take action to ameliorate the continuing economic stagnation in many black communities and challenge the “prison-industrial complex” and the way police target young black men. But he proved to be a disappointment. Very little changed in the conditions facing African Americans. Obama failed to intervene in the execution of Troy Davis in Georgia in 2011, who many believed innocent of murder. He failed to protest the acquittal of the man who killed Trayvon Martin in Florida in 2013. Soon #BlackLivesMatter joined with several other new groups such as Chicago’s Black Youth Project 100 to help fill a void in black political organizing left by the demise of SNCC, the Panthers, and other militant groups some 40 years earlier. The movement grew rapidly following the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 8, 2014, and the horrified response when his body was left in the street for four and a half hours while the police kept his parents away at gunpoint and with dogs. This tragedy among several others that made headlines “tipped the scales.” Ferguson Action soon joined what was now a broad movement that spread throughout the country. Its component groups avoided entanglement with the traditional civil rights organizations seen by the black youth at the center of the movement as “too little too late.” Its demands range from demanding police accountability (civilian review boards, body cameras, better recruitment and training of police) to the beginning of moves to focus on the structural problems (segregated housing, chronic unemployment, collapse of educational infrastructure, high crime rates, and so on) that create the context in which police feel free to exercise lethal force to protect themselves and “society.”

The movement’s multiple organizations and its decentralized and proudly leaderless structure (similar to Occupy Wall Street and its offshoots), using the tools of social media and large-scale demonstrations, have brought attention to every new police atrocity. But as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor rightly points out, “The long-term strength of the movement will depend on its ability to reach large numbers of people by connecting the issue of police violence to the other ways that Black people are oppressed.” This is the only path to turning small-scale reforms into a long-term strategy that strikes at the heart of the social system. If and as this occurs, there will need to be coordinating bodies, which will be a challenge to the informality that is so valued by young activists today.

At this point police violence has been considered a black and Latinx issue almost exclusively. I think the reality is that the movement will not be able to go beyond small-scale (and necessary) reforms in this area until whites also protest police shootings. Although black men are about two and a half times as likely to be shot by police as whites, it is nevertheless true that about twice as many whites are killed every year. Official data, which are surely an undercount, say that a total of about 1,000 people are killed and 2,000 more wounded every year. This figure has changed very little in recent years. In 2018 the fairly accurate Washington Post data base reported 452 whites, 229 blacks, and about 147 others including Latinx killed.

Whether the new movement will translate into the kind of social change agent we saw in the civil rights movement of the 1960s remains to be seen. Whether it will move beyond reform to a deeper challenge to the social system is an even more open question. The civil rights movement overall was never intended to be more than a reform struggle, except in the eyes of the radicals in SNCC, CORE, the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and Malcolm X. Martin Luther King and the handful of his adherents who saw the philosophy of nonviolence as a way of life more than merely a tactic intended the movement to go far beyond integration as a goal. All of these understood in some way that if real equality in all spheres of life, including the economic dimension, was to be achieved for the whole of the black population, nothing short of a revolutionary change in the social system would be required. The political state correctly understood and feared these elements of the civil rights struggle and destroyed them piece by piece.

The political reforms envisioned by civil rights activists decades before the 1960s have been substantially won. The movement to alter, much less abolish, the “prison-industrial complex” and its associated police systems has as yet made little progress. Beyond that, the revolutionary changes required for full equality and liberation from racism and oppression will require far larger movements than we see at this moment.

Notes

- Julian Bond, “SNCC: What We Did,” Monthly Review v. 52 no. 5 (Oct. 2000).

- Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Harvard University Press, 1981), 172, 173.

- Debbie Louis, And We Are Not Saved (Doubleday, 1970), 219.

- Mathew J. Countryman, Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia (Univeristy of PA Press, 2006), 9.

- Carson, 290.

- Bob Zellner, The Wrong Side of Murder Creek (New South Books, 2008), 294.

- James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (University of Washington Press, 1977), 496-497.

- Quoted by Doug McAdam, “The Decline of the Civil Rights Movement,” in Jo Freeman and Victoria Johnson, (eds.), Waves of Protest: Social Movements Since the Sixties (Rowman and Littlefield, 1999), 343. For more, see Oppenheimer, “Mobs, Vigilantes, Cops, and Feds: The Repression of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee” in New Politics v. XIV No. 1 (Summer 2012).

- Emily Stoper, “The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee: Rise and Fall of a Redemptive Organization,” in Freeman and Johnson, 360.

- Counterintelligence Program: “This program has as its objective the neutralization of black extremist groups, the prevention of violence by these groups and the prevention of coalition of black extremist organizations.” Neutralization meant, according to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, efforts to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” groups including CORE, SNCC, even the SCLC plus others including the Nation of Islam and of course the Black Panther Party. For more details see Carson, 260-264.

- Samuel Farber, Social Decay and Transformation (Lexington, 2000), 75.

- Joshua Bloom and Waldo Martin Jr., Black Against Empire (University of California Press, 2013), 365.

- Farber, 75.

- Countryman, 9. Deindustrialization refers mainly to the decline of manufacturing in urban areas.

- Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward, Poor People’s Movements (Vintage, 1977), ch. 4.

- Aldon D. Morris, The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement (Free Press, 1985), 287.

- Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Haymarket, 2016), 154.

- Taylor, 182-183.

- For a more detailed look, see Oppenheimer, “Racist Terror, Then and Now,” Against the Current #178 (Sept.-Oct. 2015).