Mobs, Vigilantes, Cops, and Feds: The Repression of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, or "Snick") came out of the sit-in movement that began on Feb. 1, 1960 in Greensboro, N.C. Its founding convention was at Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C. April 15-17 that year. 200-plus-delegates representing student civil rights organizations at 52 colleges and high schools attended. By the summer of 1964, SNCC was able to mobilize approximately 1250 staff and volunteers for the famous "Freedom Summer" campaign to register black voters and to run "Freedom Schools" for black youth in Mississippi. That fall SNCC counted 160 full-time staff.

In December, 1973, nine years after the peak of its influence, the New York office of the FBI ended its surveillance of SNCC and closed its file, noting there had been no activity for several years "and that future prospects for such are exceedingly faint."[1]

SNCC changed from an integrated mass nonviolent direct action reform movement to a revolutionary black cadre organization.[2] It was destroyed by a combination of strategic errors and miscalculations, internal discord, and indirectly by its own successes. Its major strategic turning point was when it adopted the slogan of "Black Power," which soon led to the exclusion of whites from the organization. This may have led to a temporary uptick of organizing, but it meant a significant loss of experienced personnel, and a major decline in financial support. It was a big step towards SNCC’s isolation.

But probably the single most important contributing factor to its demise was violent, as well as secret, repression: by mobs of white Southern citizens, by vigilante gangs (especially the KKK), by local and state police forces, and by the federal government (mainly the FBI). There is no disagreement by anyone in or around the movement, or those who have studied it (not mutually exclusive categories) as to the importance of this factor. Nor is there any disagreement that the categories "mob," "vigilantes," and "cops" all overlap: mobs were instigated by the Klan and allied groups such as the Citizens Councils, cops were Klan members, cops participated in and were complicit in vigilante activity, cops stood aside and allowed mob violence against people exercising their rights as citizens. The FBI (under J. Edgar Hoover) also looked the other way on numerous occasions, delayed action in other instances, and infiltrated SNCC and attempted to destroy it in its COINTELPRO operation.[3]

The South, in the years after World War II, had more in common with South Africa than it had with the U.S. North. More than half of all blacks were living in rural areas. A "Black Belt" of counties in which blacks were the majority or close to it ran from rural Maryland to East Texas. Their political influence in this belt was nil. In county after county where blacks were 60 percent and more of the population, not a single one was allowed to register to vote. All community facilities were segregated, or blacks were excluded entirely: restaurants, public libraries, swimming pools, movie theaters, bus terminal waiting and rest rooms, and of course housing and education including higher education.

The 1960 sit-ins[4] came on the heels of the 1954 and 1955 Supreme Court decisions requiring a "prompt and reasonable start" to eliminate segregated schools. This triggered a vast movement to resist school integration throughout the South and to the founding of the Citizens Councils, supposedly a more respectable version of the KKK, which itself enjoyed a big revival. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, under the leadership of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., was next (Dec. 1955-Nov. 1956). There were sit-ins to integrate the eating facilities of restaurants and chain retail stores prior to Greensboro, but they did not catch on. In Greensboro, however, contacts and resources were available to what would soon be a movement; the press and radio carried reports, and within sixty days the sit-ins spread to nearly 80 communities from Ohio to Florida. Most of this activity was in the "Upper South," that is, in communities where blacks did not constitute a major numerical and potentially political threat, in communities that were, by the standards of the day, "progressive." In March, 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was able to report that 138 communities had integrated at least some facilities.

Yet this did not come easily. Nearly 1,000 black and white civil rights activists were arrested during the first two months of the sit-ins. Hundreds of students suffered tear gas, police dogs, burning cigars on clothing, and beatings. Nonviolence training in the form of workshops did not prevent hostile and brutal attacks by local whites, especially white youths, but did probably limit the damage. Local police normally either absented themselves, or stood by as these attacks took place, when they did not actively intervene to arrest the sit-in students or chase them from the premises with dogs.

In the Deep South (South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana) the nonviolent movement and its community allies met with intense repression. Yet sit-ins and other nonviolent demonstrations (rallies, marches, picketing) did take place in places like Montgomery, Alabama (where the police department was heavily Klan), Columbia, South Carolina (where on one occasion 192 students were arrested while marching around the State Capitol building), and Orangeburg, South Carolina (where some 500 students were arrested and hosed down in a stockade in freezing weather). In these states integration of any facilities, never mind voting, was viewed by most whites as a threat to the basic social and political order, not without reason. Black participation in elections would (and ultimately did) lead to the election of black mayors, sheriffs, and other local and state officials. Intense resistance by local and state authorities, backed by mob violence, the Klan, and local Citizens Councils was the common response to any attempt to alter the status quo.

On April 17, 1960, SNCC was officially established. Even here, at black Shaw University, which hosted some 200 participants including King and others from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), two visitors to the conference were assaulted, one while picketing the local Woolworth "five-and-dime" store.

Although Shaw welcomed the conference, other Southern black colleges were generally hostile to the movement. They were dependent on white philanthropy, and their survival (especially the state colleges) depended on the good will of segregationist governors and legislatures. These proceeded to pass various kinds of laws restricting or banning picketing, allowing store keepers to bar whomever they wished, and providing local police with new "anti-riot" weaponry. The colleges themselves expelled student leaders (about 45 during 1960) and fired professors sympathetic to the movement (about ten that year alone). The cases of academic freedom and tenure coming to the attention of the American Association of University Professors increased from 37 in 1961 to 55 a year later; the majority of censured institutions were located in the South for many years after that.

Mobs

Segregationist mobs showed up on innumerable occasions upon the appearance of blacks (with or without white allies) attempting to integrate various facilities or register to vote. The assaults on the Freedom Riders in May, 1961, were atypical only in their setting: On May 4, 13 volunteers recruited by CORE (7 blacks, 6 whites) set forth in two buses from Washington, D.C. to test Court rulings banning segregation in interstate travel. Two of the 7 blacks belonged to SNCC. They were assaulted first in Rock Hill, S. C. Then a mob attacked the buses in Anniston, Ala. One bus was burned, the mob beating the riders as they fled. The second bus continued to Birmingham, where a white mob attacked the riders as they debarked for the waiting room of the terminal. The police, in cahoots with the Klan, were absent. The FBI did nothing, claiming (as in other instances) no jurisdiction. CORE was forced to discontinue the ride because no bus driver could be found to take the riders further. But now students from predominantly black Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn., vowed to continue the ride and on May 17 a group took a bus to Birmingham. All ten students (including two whites) were promptly arrested and a day later escorted to the Tennessee border. On May 20 a new group of riders left Birmingham for Montgomery, the state capital, escorted by police. The police disappeared as the bus approached Montgomery and when the bus arrived, a mob first attacked reporters, then the riders and a white Justice Department official, John Siegenthaler. Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent federal marshals in case of further trouble. However, the following evening, when the riders and local blacks assembled to hear Rev. King speak in a local church, whites began to riot outside, forcing the congregants to remain inside for the night. The governor of the state at first refused to intervene, but at the threat of federal troops being sent finally declared martial law and state troopers dispersed the mob.

Voter registration soon became SNCC’s priority. In August and September, 1961, SNCC workers went to rural Mississippi to persuade local blacks to register. Progress in the face of assaults by local whites, including officials, and arrests, was impossible. On August 15 SNCC worker Bob Moses was jailed for two days; following his release he was assaulted and severely beaten. His assailant was subsequently acquitted by an all-white jury. In McComb, Miss., arrests and assaults followed a black student rally at City Hall. Bob Zellner, a white SNCC worker who was a native Alabaman, was beaten and severely injured. In Southwest Georgia, the number of incidents of blacks being attacked during demonstrations in 1962 and 1963 ran to eight single-spaced pages.[5]

There were several instances of mob activity that amounted to armed insurrection. The most notorious was at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Miss. in 1962. James Meredith, a black Air Force veteran, applied to the all-white University in early 1961. He was rejected. Ultimately the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the University to admit him. What happened then, in summary, is that by the time Governor Ross Barnett, who had sworn to use the state police to thwart the order, relented in the face of federal marshals, the town of Oxford was teeming with armed men, including units of the KKK. There was solid information that many more armed men were on the way. The marshals were insufficient to deal with such an insurrection. President Kennedy ordered in the Army, the vanguard unit of which was the highly trained riot-fighting 503rd Military Police Battalion of the 82nd Airborne Division from Ft. Bragg, N.C. These were all integrated units. In violation of direct orders to send all black troops back to Ft. Bragg, this unit, including a Chemical Company (gas), took off for Ol’ Miss.[6] Other units removed their black soldiers and kept them away from the action, despite protests from both men and officers. President Kennedy also federalized the Mississippi National Guard. By the end of this episode, 31,000 soldiers including units of the 101st Airborne and 11,000 Mississippi National Guardsmen had been called in—three times the number of U.S. soldiers in West Berlin at the time. A two-day battle (Sept. 30-Oct. 1, 1962) between armed mobs, marshals, and soldiers then ensued, as Meredith was quietly sneaked into the Lyceum Building, the administrative center of the University, to register. Two people were killed; 160 soldiers and 28 marshals were injured. Meredith graduated in August, 1963. In 1966 he would appear in the headlines once more.

Vigilantes

Vigilantes are people (individuals or groups) who believe that the law is unwilling or incompetent to defend the social norms of a community. Using various unlawful tactics including beatings, arson, and murder, they "take the law into their own hands." The Ku Klux Klan, from the post-civil war era to date, is a vigilante organization. During the 1960s individuals acting with or without organized assistance carried out numerous bombings and assassinations. A vigilante acting, as far as we know, alone, assassinated Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968.

On Sept. 5, 1961, Herbert Lee, a local black who had assisted SNCC in Mississippi, was murdered by a white State Representative, who was never indicted. A black witness to the shooting was beaten and several years later murdered. 1963 was marked by assassinations and bombings. Among those murdered were William Moore, a white civil rights activist who was assassinated on April 20 in Alabama; Medgar Evers, a NAACP leader in Mississippi, was shot down on June 12. A notorious local segregationist, Byron De La Beckwith, was charged but after two trials with all-white juries, no conviction was forthcoming. (In 1989 new evidence was produced, and he was finally convicted and sentenced to life. He died in prison in 2001.) On Sept. 15, four girls aged 11-14 died in the bombing of a black church in Birmingham, Ala.

Late in 1963 the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), a coalition of civil rights groups with SNCC as the strongest component, CORE, and other groups, began to organize a massive campaign to register black voters in Mississippi. In mid-June, 1964, some 300 college students, mostly white Northerners, were brought to Oxford, Ohio, to prepare for the campaign. At the training sessions, a representative of Robert F. Kennedy’s Department of Justice, John Doar, told the volunteers that the federal government could only investigate; it could not protect voter registration workers. He said protection was up to local police, which in effect meant the opposite, since it was well known that police in Mississippi were collaborators, if not actual perpetrators, of outrages against civil rights activists. The volunteers were shocked. But Doar’s statement was patently untrue. Two years earlier President Kennedy had sent federal troops to the University of Mississippi to assure James Meredith’s right to enroll. Federal troops had been used on any number of occasions to enforce court integration orders, as in Little Rock, Ark. in 1957 to enforce a school integration order. Moreover, there are many federal laws (not to mention the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution) that were at President Johnson’s hand.[7]

On June 21, 1964, at the beginning of "Freedom Summer," three volunteers including two members of CORE, James Chaney (black) and Michael Schwerner (white), and one fresh from the Oxford orientation, Andrew Goodman (white), went to investigate the burning of a black church, the Mt. Zion United Methodist, near Philadelphia, Miss. The church had hosted civil rights meetings and had agreed to sponsor a Freedom School. It had been burned to the ground. The men disappeared after having been briefly arrested in Philadelphia. Their bodies were found on August 4. During the search, the bodies of three other black men, one wearing a CORE T-shirt, were also found. The record is clear that the FBI was notified immediately when the men went missing but took no action in the critical two days between the disappearance and the date (it would be established) of the murders. The FBI in Mississippi at that time was all white, and most agents were native to the state. Eventually the U.S. Department of Justice charged 18 men with violating the civil rights of the victims (since the state had refused to indict for murder). These included the Sheriff, the Deputy Sheriff, and a Baptist minister. Most were acquitted, or served short sentences. The minister was retried in 2005, convicted, and sentenced to 20 years for each of the murders. He was 80 at the time. He was sent to the Mississippi State Penitentiary, better known as Parchman, which in the 1960s had hosted many civil rights workers including some of the Freedom Riders.

The murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were the work of Klan vigilantes in complicity with local police, assisted by foot dragging by the FBI. The project went forward, despite continuing attacks, including bombings, many assaults, and about 1,000 arrests. COFO collected data about these events that went to 26 pages. They ranged from murder to such relatively minor incidents as harassing arrests for vagrancy and "traffic violations." Not all were related to civil rights activities, but easily 90 per cent were, and many were police-related rather than vigilante.

Vigilante activity continued in many parts of the South. In the spring of 1965 a white SNCC staffer, Ira Grupper, paid a visit to Vernon Dahmer, a black businessman who was the head of the Hattiesburg, Miss. NAACP. Nailed to a tree in Dahmer’s yard was a KKK recruiting flyer, clearly meant as a threat. Dahmer tore the flyer off and gave it to Grupper. The following January, after an apprehensive Dahmer had sent his family away, his house was firebombed and he was killed. Also that January, SNCC volunteer Sammy Younge, a Navy veteran, was shot and killed as he tried to integrate a "white" bathroom in Tuskegee, Ala. Then in June, James Meredith, of Ol’ Miss fame, decided to walk from Memphis, Tenn. to Jackson, Miss. to promote voter registration. He was shot and wounded by a sniper on the second day of the walk. SNCC, CORE and King decided to continue the march. It was during this march that Willie Ricks, a SNCC organizer, proposed the slogan "Black Power" to arouse local blacks to join the voter registration campaign. It was quickly adopted by SNCC’s main leader at the march, Stokely Carmichael, at which point the NAACP withdrew from the march. Even Meredith was opposed to the slogan. The march was attacked by white mobs and the police before it finally reached Jackson, the state capital.

Cops and Feds

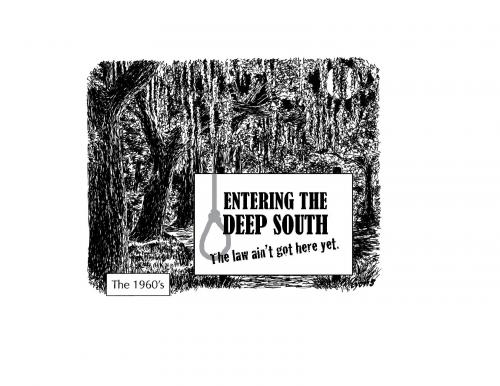

The fundamental fact was that in the Deep South blacks in general and civil rights activists in particular (including whites) had no legal protection. When Charlie Cobb Jr. went to Ruleville, Miss. to initiate a voter registration campaign, he and two colleagues were stopped by a white man with a pistol, who ordered them into his car. This man was the mayor, the justice of the peace, and the head of the local Citizens Council. The three were told to get out of town. When they protested that the U.S. Constitution gave them the right to be there, the mayor’s reply was, "That law ain’t got here yet."

In Orangeburg, S.C. there were at least three major confrontations with the police: in March, 1960, with 500 arrests (mostly or all students) following a series of marches protesting segregated facilities; in August-October, 1963, further marches led to over 1300 arrests (including black community leaders); and then the "Orangeburg Massacre" in February, 1968. In this incident, after a series of student demonstrations about university policy, and about still segregated facilities in the downtown area, police backed by the National Guard occupied the campus. Believing that a shot had been fired at a police officer, police fired on students. Thirty-three of them were shot, three died.

Thousands upon thousands of civil rights activists were arrested during the 1960s, both individually and in groups, all while engaged in activities presumably protected by law. On October 19, 1960, 31 demonstrators including Rev. King were arrested in Atlanta, Ga. at a department store sit-in. Candidate Kennedy telephoned his personal sympathy to King’s wife, and the local judge was persuaded to release everyone. Kennedy won the election that November by a very narrow margin, attributed by many observers to a significant swing by black voters from their traditional Republican affiliation, some very likely influenced by the arrests and Soon-to-be Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy’s intercession in the case.

Police arrested Freedom Riders on numerous occasions. Hundreds of arrests accompanied voter registration attempts over several years. In February, 1962, Charles McDew, who was then SNCC chairman, and two other SNCC workers were arrested in Baton Rouge, La. on criminal anarchy charges based on their membership in SNCC, which was thought to be seeking the overthrow of the state government. McDew and Bob Zellner were jailed for 35 days in "sweatbox" cells that could well have killed them. Zellner had already been convicted on similar charges in Albany, Ga. and served a month on a black "chain gang" repairing roads even though he was white. He was not endangered since his affiliation with SNCC was well known to the black convicts.

In Cambridge, Md. the Maryland National Guard was called out to block a march intended to protest the appearance of segregationist Governor George Wallace of Alabama at an all-white rally on May 11, 1964. Several of the leaders of the march were promptly arrested and the rest subjected to a gas attack. Guardsmen then began to fire, at which point apparently some local blacks began to fire back to protect the fleeing demonstrators.

Early in 1965 Rev. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference initiated a voting rights campaign in Selma, Alabama. King was arrested Feb. 1, setting off marches that led to a thousand more arrests including hundreds of school children. In March, following the shooting of a black protester, Jimmy Lee Jackson, by a state policeman, SCLC decided on a march from Selma to Montgomery to publicize the disastrous conditions faced by blacks in that state. About 2,000, including a well-organized team from SNCC, began the march on March 7. At the Pettus Bridge just outside Selma the marchers were ordered to disperse and when they did not, the police attacked using clubs and tear gas. There were many injuries. SNCC chairman John Lewis (now Congressman) was hospitalized with a fractured skull. The march resumed a few days later only to be halted by police once more. King, at the head of the march, then turned it around in order to avoid further violence. During the following days three white clergy who supported the movement were attacked. One, James Reeb, died of his injuries. In contrast to the shooting of Jackson, this incident created a public uproar. The march finally did continue to Montgomery, accompanied by Army and Alabama National Guard troops. On March 25, after a rally at the capitol, Viola Liuzzo, a white volunteer who was driving to Montgomery, was killed by a sniper.

It was clear by 1966 that local authorities were willing and able to come down heavily against civil rights demonstrators. In Atlanta, after a riot broke out following a police shooting, Stokely Carmichael and several other SNCC workers were arrested and charged with inciting to riot (a typical charge). Their convictions were later overturned on appeal. SNCC leader James Forman, probably the leading theoretician of SNCC, concluded at the time that "the total power structure of the United States…was out to destroy SNCC."[8] Following a talk by Carmichael at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., April 8, 1967, an incident, again involving the police, triggered a riot. Police riot squads fired, hitting a building at nearby black Fisk University, and injuring several students. SNCC was blamed for this riot and its offices in Nashville raided. Several SNCC workers were arrested. At Texas Southern University in Houston, University officials prohibited the formation of a "Friends of SNCC" chapter. That May, during a mass student demonstration protesting this prohibition, police fired into dormitories, invaded and vandalized rooms, and arrested 481 people.

It should not be assumed that police repression was restricted to the South. SNCC and other direct action civil rights groups, including the Black Panther Party, were subjected to frequent police harassment, raids, and (in the case of the Panthers) even murder. In April, 1968, Panther Bobby Hutton, a teenager, was killed during a shootout with Oakland police even as he was surrendering, and Eldridge Cleaver was wounded. The Chicago police killed Panthers Fred Hampton (asleep and apparently drugged) and Mark Clark during a raid on Dec. 4, 1969. From March, 1968 to December, 1969, 19 Panthers and sympathizers working with them were killed.

In Philadelphia, Pa., in August, 1966, some 80 police backed up by a thousand more raided the SNCC office, its library, and two residences housing local militants. Four people were arrested and charged with possession of dynamite. Eventually the charges were dropped, but SNCC’s efforts in Philadelphia came to a halt. SNCC warned its staff against "plants," frameups, and other attacks by the government intended to destroy the organization. In Chicago the SNCC office was also targeted by the police. SNCC’s lead organizer left for exile in Tanzania. The Philadelphia Panthers suffered constant police harassment and in August, 1969, Panther offices were raided. By 1973 the Panthers had disappeared from the Philadelphia scene.

By the spring of 1967 SNCC joined the Panthers in openly advocating the right to armed self-defense (in practice nonviolence had been abandoned for some time). The new chairman, H. "Rap" Brown was quoted as saying "if America chooses to play Nazi, black folks ain’t going to play Jews." Its claim to be "student" was outmoded as well, and by then it was coordinating very little. Following a speech at an anti-Klan rally in Cambridge, Md., a riot broke out, the National Guard was sent in by Gov. Spiro Agnew (later Richard Nixon’s Vice-President), and Brown was arrested for arson and a few days later faced, for a second time, a weapons charge. SNCC staff was down to seventy.

The government’s two-pronged strategy was becoming clearer: repression on the one hand, and active recruitment by Lyndon Johnson’s anti-poverty programs on the other, although top leaders who had become notorious were excluded. The attraction of regular paid jobs, and the ability to support families, while actually organizing in the service of programs that were supposed to involve "maximum participation of the poor" could not be denied. After 1965, civil rights legislation passed under Johnson promised new opportunities in the realm of practical politics in the Democratic Party. Moreover, the constant talk of revolution and guns was apparently taken seriously by the authorities. "The government was on the offensive and everyone who had taken a revolutionary leadership position seemed to be fair game."[9]

Surveillance of movement activists, even by the Internal Revenue Service on alleged tax violations, became more intense. The government’s strategy immobilized resources as activists were forced to divert attention to legal issues. COINTELPRO and other government actions (including the use of agents provocateurs) contributed greatly to creating an atmosphere of distrust within SNCC, and between it and other organizations. The FBI fabricated letters with fake threats by the Panthers to murder James Forman and Stokely Carmichael in order to stoke differences between the two groups. At SNCC’s staff meeting in Atlanta in December, 1968, two of the 28 in attendance were FBI agents. One long-time staffer believes that FBI informers had been monitoring SNCC from the first, a notion that would not be surprising to older readers of this journal. Soon, battle fatigue would set in for some SNCC workers.

Following the assassinations of King and Robert F. Kennedy, and the police riot at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, urban guerrilla warfare became a topic of conversation both within radical black circles and its white sympathizers, and among the police and military. Many black activists (and many whites in and around Students for a Democratic Society, plus the usual left sects) concluded that efforts at reform had become futile in the face of repression, and that the only realistic road was armed struggle. The film The Battle of Algiers was popular on black college campuses. I.F. Stone, in his weekly newsletter commented on August 19, 1968 that "we face a black revolt…that the black ghettos regard the white police as an occupying army…that guerrilla warfare against this army has begun…" In Army magazine a Colonel Robert B. Rigg predicted, "in the next decade at least one major metropolitan area could be faced with guerrilla warfare requiring sizable United States army elements." Local police forces developed elaborate contingency plans, special tactical units, and the latest in counter-insurgency weaponry to deal with the feared onslaught of black guerrillas. On the ultra-right, the John Birch Society, the Minutemen, the Klan and similar groups were also preparing for race war.

SNCC’s mistake was to take state repression for a sign of weakness on the part of the power structure. SNCC only slowly came to understand that repression was now undergirded by a well-organized political backlash against the movements of the 1960s, especially against advocates of black power, which was widely portrayed as a call for violence against whites. SNCC was now at an impasse: The 1964 and 1965 Civil Rights Acts supported black voting and outlawed segregation. The more pragmatically oriented SNCC workers quit to work in the Democratic Party. In the South it was rapidly becoming the "black party" as whites defected after the passage of the 1965 Act. A number of SNCC veterans were now active in anti-poverty programs.

By 1966 only a handful of the many who had enlisted in 1960-64 remained. Conflicts with other civil rights organizations had become irreconcilable. Bob Zellner summarized the problem: SNCC began with three important tools. One was nonviolence, religiously-motivated, superbly suited for public relations (outside the South and throughout the entire observant world), and effective in changing "race relations" in Upper Southern states in significant ways, if not completely. The second was its interracial composition, also important in public relations and fund-raising. The third was its commitment to long-term organizing and the training of local leaders. The first and the second were abandoned by late 1966. Nonviolence was abandoned in the face of Southern mob and police terror. Going all-black was the consequence of the move to "Black Power." The third, grassroots organizing, was gradually whittled away as more and more SNCC workers took the route of working in various reform campaigns. The remaining militants felt increasingly isolated, yet were more convinced than ever that the revolutionary road, however vaguely defined, was correct. But that rhetoric led to further isolation and abandonment by liberals and mainstream civil rights organizations, and increased attention from the federal government.

Going into 1970, "Rap" Brown, the SNCC chair (the name had by now been changed to the Student National Coordinating Committee) still faced gun charges in Maryland. On March 9, the day before his trial, William "Che" Payne and Ralph Featherstone, who were to pick Brown up and take him to court, were both killed when a bomb in their car exploded. Brown then disappeared, going underground in Canada, but then in an episode still unexplained was wounded in a gun battle with New York police following a robbery. He served five years in the notorious Attica prison, where he converted to Islam, changing his name to Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin. After his release he moved to Georgia where, in 2002, he was convicted of murdering a black police officer. He is currently serving a life sentence in a super-max federal prison.

After the killing of the two SNCC workers, organizing activity virtually ceased. Purges and resignations among the remaining members continued. The FBI reported, in May, 1971, that in recent months SNCC had not "participated in any demonstration or disruptive activity, and it is believed incapable of accomplishing same in view of limited membership, lack of funds, and internal dissention."

It was over. The state had demonstrated that open black defiance was dangerous and suicidal. Black militants were imprisoned, assassinated, or they fled into exile. Stokely Carmichael, who had been expelled from SNCC for his association with the Panthers, changed his name to Kwame Tourè, and died in Guinea in 1998. Others, such as James Forman, who had also quit SNCC to work with the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit, continued to be active. The League faced harassment and violence at the hands of the police (plus the bitter opposition of many white workers and the Auto Workers union officialdom, including its black officials) struggled into the 1970s, suffered a series of splits, and finally expired. But that’s another story. Forman died in 2005.

Could SNCC have gone another route, could it have rejected the "Black Power" slogan, thus avoiding repression and again becoming a major factor in civil rights and American politics more generally? Probably not. Black power was certainly in the air before the Meredith march of June, 1966. Black nationalism in general and the Nation of Islam and Malcolm X in particular had attracted wide attention among younger blacks. The slogan of black power, joined to armed self-defense, recruited many for whom nonviolence had never made sense. The opposition to Malcolm X’s militancy by the civil rights establishment made him even more attractive. Several SNCC leaders met with him just prior to his assassination on Feb. 21, 1965. The Black Panther Party soon became an increasingly attractive alternative model for SNCC and others impatient with the slow pace of progress for blacks.

Could SNCC have maintained at least a formal commitment to nonviolence while not criticizing local blacks who had, and used, arms? Could it have adopted "Black Power" and stayed committed to nonviolence? Not if it wanted to maintain its militant reputation and avoid being side-lined, given the temper of the times, especially in the ghettos of the North amidst the scenes of riot and police and national guard violence.

CORE had also abandoned its nonviolent tradition and adopted the black power slogan. Most of its white members, as well as James Farmer and other blacks from the days of its founding left after its 1965 convention. The momentum towards a black power strategy, however defined (and there were many definitions, from black power as support for black entrepreneurship to the theory of the ghetto as an internal colony) was irresistible. As Julian Bond recently wrote, "The current of nationalism, ever present in black America, widened at the end of the 1960s to become a rushing torrent which swept away the hopeful notion of ‘black and white together’ that the decade’s beginning had promised."[10] The abandonment of SNCC and CORE by "white" liberal and labor groups and mainstream civil rights groups such as the NAACP simply confirmed the sense that there was no alternative to a militant black power strategy if real progress towards black liberation from white (and capitalist, in some views) oppression was to be accomplished.

The FBI under Hoover made little distinction between the respectable and the revolutionary among black activists. Nevertheless, while other organizations survived, the feds were committed to destroying SNCC and the Black Panther Party by any means necessary. There are limits: the state, which by definition claims a monopoly on the "legitimate" use of violence, ultimately cannot tolerate a challenge to that monopoly, whether by black revolutionaries, or by insurrectionary mobs. The use of federal troops to enforce court decisions from Little Rock to Ol’ Miss, as well as the FBI’s role in the demise of SNCC, rather than demonstrating the state’s "neutrality," much less its weakness, reaffirmed its role as guarantor of stability and security, conditions essential to the capitalist enterprise.

Did SNCC fail? The short answer is "no." On a day-to-day level by 1970 the South was a vastly different place compared to just ten, and certainly twenty years before. "In the South," as Piven and Cloward said in 1977, "the deepest meaning of the winning of democratic rights is that the historic primacy of terror as a means of social control has been substantially diminished."[11] SNCC was central to this progress. Their veterans continue to this day to be active in progressive causes from coast to coast and even abroad.

The reforms envisioned by civil rights activists decades before the 1960s have been substantially won. The South has rejoined the Union at last. But the revolutionary changes that SNCC finally understood would be required for full equality and liberation from racism and oppression remain on the agenda.

Update: Sept. 17, 2012

Readers have called my attention to several errors in my article.

- In referring to the beginning of a voting rights campaign in Selma, Alabama, I mistakenly referred to the Southern Christian Leadership Council. It is Conference, not Council.

- I referred to federal laws that could have been used to protect SNCC voters, including Article 14 of the Bill of Rights. It is the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, not the Bill of Rights, that should have been cited.

- In October, 1960, when demonstrators including Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. were arrested at a sit-in in Atlanta, Georgia, John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert, who intervened informally, had not yet taken office. I should have said Candidate Kennedy, and Soon-to-be Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

Mea Culpa. I am grateful to careful readers who called these mistakes to my attention.

Martin Oppenheimer

Ed. Note: The text above has been changed to reflect these corrections.

Footnotes

1. Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1981) p. 298.

2. A cadre organization consists of members who make a maximum commitment to the cause, often as full-time workers, as distinct from a general membership organization where the level of commitment by most members is minimal or temporary.

3. Counterintelligence Program: "This program has as its objective the neutralization of black extremist groups, the prevention of violence by these groups and the prevention of coalition of black extremist organizations." FBI Memorandum, reprinted in Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall, Agents of Repression: The FBI’s Secret War Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement (South End Press, 1988), p. 38. Neutralization meant, according to Hoover, efforts to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize" groups including the Deacons for Defense and Justice, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), SNCC, and even Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), plus others such as the Nation of Islam. Tactics included collaborating with local police forces to arrest local leaders "on every possible charge" and to make efforts to discredit these groups in the eyes of the "responsible Negro community." (Carson, pp. 262-263.)

4. The sit-ins were a strategy in which groups of blacks, mainly students, would occupy seats in restaurants and in the eating sections of department stores such as Woolworth’s that did not serve black people, and ask to be served. When ordered to leave they would not, until closing time. They would return the following days until, it was hoped, the policy would change. Similar strategies were used to challenge segregation in other facilities such as "white" churches, public swimming pools, libraries, and amusement parks.

5. James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle, WA: U. of Washington Press, 1997), p. 274.

6. For the full story, see William Doyle, An American Insurrection (N.Y., NY: Anchor, 2003).

7. For example: "Whenever the President considers that unlawful obstruction…or rebellion against the authority of the United States makes it impossible to enforce the laws of the United States…by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings, he may call into Federal service…and use such of the armed forces as he considers necessary to enforce those laws or to suppress the rebellion." In Len Holt, The Summer That Didn’t End: The Story of the Mississippi Civil Rights Project of 1964 (N.Y., NY: William Morrow, 1965) and (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1992).

8. James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle, WA: U. of Washington Press), p. 470.

9. Cleveland Sellers, The River of No Return (Jackson, MS: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1990) p. 258. Sellers started writing this book while serving seven months in jail after being shot, then arrested on multiple charges following the 1968 "Orangeburg Massacre" incident.

10. In Leslie G. Kelen (ed.), This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement (Jackson, MS: Univ. Press of Miss.), p. 14.

11. Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Poor People’s Movements (N.Y., NY: Vintage, 1977), ch. 4.