Mali: A Neo-Colonial Operation Disguised as an Anti-Terrorist Intervention*

Translated by Dan La Botz

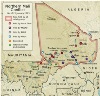

In mid-January of this year France invaded Mali, a former French colony that sits in the middle of what was once the enormous French empire in Africa that stretched from Algeria to the Congo and from the Ivory Coast to the Sudan. The French government argued that its invasion of its former colony was an anti-terrorist and humanitarian intervention to prevent radical Salafist Muslims from taking the capital of Bamako and succeeding in taking control of the country.

Critics have suggested that France had other motivations, above all maintaining its powerful influence in the region in order to prevent European competitors, the United States, or the Chinese from muscling in, but also because of its specific interests in resources such as uranium. The situation is very complex, in part because of a historic division and even antagonism between the Tuaregs, a Berber people in the North of Mali, and the black African population in the South, but also because, in addition to the various Islamist groups, there are also numerous organizations of traffickers in drugs and other contraband. In this article, Jean Batou unravels the complexity of the situation to lay bare the central social struggles taking place. – Editors

Looking back on events, it’s important to point out the real ins-and-outs of the French military intervention in Mali, launched officially on January 11 on the pretext of preventing a column of Salafist pick-up trucks from swooping down on the city of Mopti and the nearby Sévaré airport (640 km north of Bamako), and thus supposedly opening the way to Bamako, the capital and the country’s largest city. The emotions caused by the atrocities of various Islamist groups of North Mali gave this unilateral operation the allure of a humanitarian crusade supported by a large part of Malian, African, and international public opinion. Certainly the legal basis of support was weak given the illegitimacy of the government in Bamako, which—as we would learn later—had never asked for air support from France, but there was also the fact that the Malian army had been subordinated to the French, as well as the reluctance of the troops of the Economic Community of East African States (ECOWAS) to lend a hand. What then were the motives of this new French intervention in Franc Africa, whose neocolonial character stood out clearly, even if it arose in a particular local and international context?

In order to understand such a complex phenomenon as the recurrent revolts of the Tuaregs of North Mali, as well as more recently the rise of political Islam and the role played by the armed Salafist groups in the region, it’s important to take some distance from the emotional reports of the corporate media that reduced each event to simply the immediate appearance, contributing to rendering it impossible to understand. I will begin therefore by describing the social situation in Mali, a country dominated by poverty, large areas facing famine, and the growth of social and regional inequalities arising in the context of economic liberalization, an opening to foreign capital under the pressure of a succession of structural adjustment programs that began in the late 1980s. Then I’ll turn to the history of Tuareg resistance to French colonialism, but also to the centralizing and repressive policies of independent Mali, without forgetting the longstanding resentment experienced by the black people there. Finally, I will attempt to analyze the specific role of certain actors, such as international investors who have encouraged the political rivalry of competing imperialist powers, the armed and mostly foreign Salafists and the traffickers (cigarettes, drug, arms, etc.) of Sahel. I conclude this overview by arguing in favor of the refusal to support the French military intervention.

A Ravaged Country

In 2011, the United Nations Development Program classified Mali in the 175th place of 187 countries in terms of human development. The most recent statistics indicate that women give birth to 6.5 living children, of whom six die before reaching the age of five years (half of those who survive suffer from retarded development). Death in childbirth affects one woman out of 200; nine out of ten homes have no electricity, 19 of 20 have no sewer system1; three quarters of those born in Mali who are more than seven years old do not attend school, etc. And when international institutions want to show some progress in the last decade, they still have to concede that there has been a continual increase in social inequality—and of regional inequality (the homes of Gao, Timbuktu, or Kidal, in the north, have less than half the income of those in Bamako)—and growth in the number of poor people.

For the rural populations affected by recurring famines, the “lack of food” is today perceived as the number one problem. So last spring, some 13 to 15 million people of the Sahel—transition zone in northern Africa between the Sahara desert and the savannahs to the south—were facing hunger of whom 3.5 to 4 million were Malians.2 This is the remarkable situation of the descendants of a once great African empire of the Middle Ages called “Mali” by the Fulani people, a name meaning “to bring good luck.” Later, it’s true, its inhabitants experienced the brutal intensification of the slave trade that fed the Atlantic economies of the Europeans in the Americas as well as French colonization, both conducted by what can only be called terror methods. Vigné d'Octon, the nineteenth century anti-colonialist, has left this account of the taking of Sikasso (south-east of Bamako): “Everyone is captured or killed. All captives, about 4,000, herded along. […] Each European received a woman of his choice […] We are on our way back, some 40 kilometers, with the captives. Children and all those who are tired are killed with rifle butts and bayonets.”3

In these territories, death was ever present, and not just in the conquest. Death permeated the lives of the “natives,” who were dispossessed of their land, who suffered forced labor and corporal punishment, the rape of women, the reduction of food crops in favor of one-crop export products (cotton in Mali), a suffocating tax burden (which after 1908 had to be paid in cash) and innumerable humiliations. Franz Fanon drew this portrait: "The colonized, such as the people of the underdeveloped countries and like all the poor people of the world, see life not as a blossoming, not as the development of a vital seed, but as permanent struggle against an atmosphere of death. This death at point blank range is characterized by endemic famine, unemployment, morbidity and, inferiority complex and a lack of doors to the future. “4

After independence, largely controlled by the former colonial power which could count on the collaboration of a large part of the local elite,5 that heritage would lead to new famines such of those of the 1960s.6 From 1960 to1968, the Malian Modibo Keïta (recipient of the “Lenin Prize” in 1963) had used a developmentalist phraseology with a certain socialist flavor, advocating Pan-Africanism and non-alignment.7 He protested against French nuclear tests in the Sahara, succeeded in getting the French to close the bases at Kati, Gao, and Tessalit (1961), and gave support at an opportune moment to the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN). Nevertheless, he had not really succeeded in breaking with the neocolonial relationship. Samir Amin showed, some forty years ago, the limits of that experience which he at that time rather harshly called “a farce.”8 The bankruptcy of his policy, notably marked by the de facto return to la zone franc—the pegging of the Malian franc to the French franc—was followed, in November 1968, by a military coup d’état led by Moussa Traoré and the institution of a police dictatorship that would last 23 years.

This situation was reversed in March 1991 following significant union and youth mobilizations (after January), the suppression of which left hundreds dead. This social movement led a dissident group in the army, headed by Amadou Toumani Touré, to taking power, which he quickly turned back over to a civilian government. Then Alpha Oumar Konaré, lifted up by popular protests to become head of state, decided to pursue a policy of reducing public expenditures, privatizing resources, and increasing export revenues. The foreign debt that Mali inherited from the dictatorship in effect permitted France, the International Monetary Fund, and the African Development Bank to impose on Bamako even more onerous regressive social structural adjustments, which are, called—in all seriousness—a framework for the fight against poverty.9 The bleeding white of Malian society explains the emigration of some four million of its citizens, principally to Africa, but also including some 120,000 who have gone to France.

The Tuaregs: Between Geography and History

The Tuaregs are a group of about two to three million people in the Sahara and on the borders of the Sahel.10 They live principally in the states of Niger and Mali, and to some extent in Burkina Faso, Algeria, and Libya. They speak a Berber language, Tamashek, and are similar to the people of North Africa before the Arab conquest. Their settlement, their poverty, their location in the poorest neighborhoods of the cities, but also their acculturation are general trends at the regional level, promoting the formation of an outbreak of revolt endemic in large areas that separate the Maghreb (Northwest Africa) from FrancAfrica, the French sphere of influence in Africa.11 In reality, the situation of the Tuaregs is consonant with the arbitrary political architecture of post-colonial Africa that laid out arbitrary “borderlines” between the various states.

In Mali more specifically, it is extremely difficult to measure the demographic size of this people. According to the most credible sources, there are about 500,000 to 800,000 Tuaregs or approximately three to five percent of the total population of the country. In the three regions of the north, they represent however somewhere between one-third and one-half of the population of 1.5 million. However, unlike other inhabitants of this country, whose poorest people live in the countryside, it is the poorest among the Tuaregs who live in the cities, notably in Timbuktu, Gao, and Kidal, but also in Bamako. This particular circumstance could help to explain the growing influence among them of the Salafist political groups such as Ansar Dine—Defenders of the Faith—, who have used their considerable financial resources to take advantage of the resentments felt by the downwardly mobile Tuaregs.

The history of the Tuaregs and of their relations with other African peoples precedes colonization by several centuries. They are reputed to have played a role in the capture, transport, and trade in black slaves destined for North Africa or the Middle East. Their “traditional” social organization, which was very hierarchical, included a “sub-caste” of enslaved black African origin—the Ikelan or Bella—dedicated to serving in the home, salt production or agriculture. These forms of domination have partially survived the colonial era,12 and even if they are not specific to the Tuaregs13—but also to other groups such as the Arabs, the Songhaïs and the Fulani—they are deeply resented by the black Malians. While a report by the humanitarian organization Tuareg Temedt (Tuareg Solidarity) stated that thousands of people were enslaved in the Gao region in 2008, this phenomenon is due at least as much to the impact of neoliberal policies—the growth of poverty, decline of public education and the presence of the central government, etc.—as it is to the survival of ancestral practices.14

The Reason for So Many Rebellions

After the end of the 19th century, the Tuaregs offered a fierce resistance to French colonization. In January 1985 they inflicted a crushing defeat on Colonel Bonnier, who died outside Timbuktu with the rest of his officers, before Colonel Joffre could undertake his successful counter-offensive. Little by little the colonial power was able to occupy Azawad—North Mali— through a combination of bloody reprisals and the offering of privileges in order to co-opt tribal chiefs. The French authorities at the time considered the Tuaregs to be “white” people, superficially Islamized, and therefore likely to establish ties to the metropolis.15 In 1903, the colonial administration managed to conquer the principal tribal confederation, though it would take up the torch of rebellion again in the course of the First World War (1916-1917). This last general uprising would lead to a massacre. After that, all insubordination was cruelly repressed. In 1954, the colonial regime paraded the head of Alla ag Albacher, the inspirer of the resistance in Ifoghas mountains since 1923, through the streets of Boureissa to show what was in store for anyone who opposed the French authorities.

Three years after independence, the Tuareg revolt raged again in 1963-1964, led by the tribes of Ifoghas. It was partly due to the increased taxation of livestock keepers, considered backward and idle by Bamako, but it also reflected the refusal of some of the Tuaregs to be led by blacks that they still perceived as their servants or slaves. It was brutally crushed by the state-builder Modibo Keïta who did not hesitate to command the bombardment of civilian populations in the mountains, the poisoning of their wells, the machine gunning of their livestock, and forcing their children to sing in Bambara, the West African language spoken by the majority of Malians.

Hostilities broke out again from 1990 to 1995 (with an estimated 5,000 victims), leading to another wave of repression, but also to the explosion of inter-ethnic conflicts and the formation of self-defense militias among the other peoples of the Niger bend. Yet, this new eruption wasn’t comparable to that of the first half of the 1960s, since it involved many returning from Libya or Algeria, where they had gone in the 1970s or 1980s, pushed by famine, to look for work, or to fill the ranks of the Islamic Legion of Kadhafi (dissolved in 1987) as well as the Polisario Front. They called themselves the Ishumars (from the French word chômeur meaning unemployed). The musical group Tinariwen, recipient of a Grammy Award in the US in 2011 for Tassili, the best album in a foreign language, belongs to that generation in exile, which has largely broken with the traditional hierarchies.

Upon returning home, some of these young, unemployed people were recruited and formed into mobile groups, equipped with 4 x 4 vehicles and armed with light weapons, to harass the symbolic and strategic sites (such as the uranium mines at Arlit) in the neighboring state of Niger. Yet, lacking any really ideological foundation or credible political project, they have not been able to surmount their differences. In 1996, they were convinced to turn over their arms in exchange for a rehabilitation plan for their fighters, the withdrawal of the Malian army from the non-urban zones of Azawad, and the appointment of some Tuaregs to positions in the national institutions, as a token of the recognition of the claims of their people. This policy coincided with a temporary end to the drought and a rise in the price of livestock. However, arguing that the agreement had not been respected, the Tuaregs revolted; the uprising raised its head again in 2006-2008, temporarily halted by an Algerian mediation effort. The rebellion coincided with a new exacerbation of social inequalities. Similar developments took place in Niger in 2007-2009, when four employees of the French Areva company were abducted (June 2008) and liberated a few weeks later. The matter concluded through the mediation of Libya, which was then closely allied with France… Hostilities broke out again in North Mali in January 2012, in the midst of a terrible drought, but, following the collapse of the Kadhafi regime, due to the influx of arms and mercenaries who had either fought for the dictator or with the revolutionary opposition) and who had passed through either Niger or Algeria.16 In the middle of that month, a group of Tuareg rebels, apparently linked to the future Ansar Dine Salafist movement (created later in April), summarily executed 80 police officers, soldiers, and civilians at Aguelhok (160 kilometers north of Kidal), with that giving the signal that there would be war without mercy. At the same time, nearly 400,000 people fled the devastating battles that affected the region. If the Tuareg fighters at first seem less divided amongst themselves than they were in the 1990s, with the building of the Azawad National Liberation Movement (MNLA), they soon had to deal with the competing formation of the Ansar Dine Salafist group, led by Iyad ag Ghali, one of the principal leaders of the uprising of the 1990s, who in the meantime had served as a Malian diplomat to Saudia Arabia. It should be considered that the relative portioning of these forces, but also the homogeneity of each of them, remains limited, as has been shown by succeeding quick changes in politics of the MNLA and the recent split in Ansar Dine. In addition, neither one of them represents a very large sector of the population.

Coveted Natural Resources

Foreign capital is more and more interested in Sub-Saharan Africa, which, far from being a sub-continent ignored by globalization, has experienced growing interests in the areas of agriculture, mining, and energy. In Mali, the Presidential Council for Investment (CPI), founded in 2003, is made up of representatives of numerous multinationals—Anglogold, Barclays, Coca-Cola, etc.—and the FMI and the World Bank also attend its meetings. Beyond that, the Malian Agency for Promotion of Investments (API), created in 2005, notes that the influx of foreign capital is encouraged without restrictions (and permits the repatriation of dividends and of proceeds from sales or liquidations). In terms of land, the API asserts that 2.4 million hectares of arable land—of 4.7 million —are available to investors,17 the great majority of whom are foreigners, notably for the production of biofuels, even though the overuse of land—including cotton plantations18—causes accelerated degradation and turns productive land into a desert.19 In the area of mining, subterranean Mali contains many more resources than have yet been exploited. Its production of gold made the fortune of South African Anglogold and put the country in the 16th place in gold production worldwide (2009). Yet, the working conditions are deplorable, in particular for the child laborers less than 15 years old, and the risks to the environment don’t in any case justify the economic benefits, which serve essentially to enrich the stockholders (20 percent of the capital is in Malian hands) and to service the foreign debt. The exploitation of other important mineral deposits—semi-precious stones, bauxite, uranium,20 etc.—is still in the realm of speculation.

There are great hopes in the future extraction of petroleum in the north of the country, in particular in the Taoudeni basin21, but the drilling, mining, and transportation of hydrocarbons still pose technical, logistical, and financial complex problems, not to mention security issues. If French energy interests are linked to its military intervention in Mali, they are those of the Areva nuclear energy company which monopolizes the exploitation of the uranium deposits at Arlit in Niger (the world’s fourth largest producer), located 300 kilometers east of the border of the Malian region of Kidal. One will recall that a third of the fuel consumed by the French nuclear plants comes from this country. Moreover, Areva has just signed an agreement for the exploitation of the Imouraren basin (the second largest reserve in the world), 80 kilometers to the south of Arlit, 60 percent of the capital of which is the property of this company. A first tranche of investment of 1.2 billion euros has been already programmed. The French investors don’t at the moment hold the privileged positions in Mali that they do in other countries of FrancAfrica, one more reason today for claiming economic returns on military investments, beyond that of the international promotion of French war materiel. Yet, as the Survie Association notes, France has achieved a trade surplus on the order of 300 million euros with Mali, five times greater than its foreign aid to that country.22

Salafists and Dealers

The situation on the ground is complicated by the growth in power of two types of actors who largely coincide as they dispute the Sahel region:

1) The “jihadists” mostly foreigners who have emerged from the Algerian Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) of which a rival faction, the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) is specifically interested in Sub-Saharan Africa.

2) There are dealers of all sorts, in particular those who deal in cocaine and heroin, and their local contacts. Clearly, the financial sources and the political relationships of these two types of actors are a great deal more important and more diverse than those of the Tuareg rebels.

I. The rise of the Salafist armed groups of the Sahel is a result of their defeat in Algeria, but also of their weakening in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) is reputed in the last few years to have established a new world center for terrorist activities in the African nations of the Sahel, from Sudan to Mauritania. It’s hard to measure the effective forces claimed by the AQMI which was formed after the denial of the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) electoral victory by the Algerian Army, in 1992, which preceded the implacable repression of the Armed Islamic Group (GIA), a dissident faction of which escaped from the Algerian cul-de-sac and founded the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) in 1998; it became linked to international “jihadism” in the first half of the 2000s, before it took the name Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in 2007.

One would have to be pretty clever today to figure out how these groups from that exploded nebula function and how many armed troops they have, pulled as they are by the gravitational forces of hidden sponsors and also by the opportunities of lucrative traffic in hostage taking and ransom.23 It is, however, reasonable to distinguish these from political Islam following the Salafist line and with a certain popular base in the society, such as Ansar Dine in North Mali.24 The latter attempted to exploit to its advantage the endemic poverty, accentuated by shock treatments by the international financial institutions and implemented by the neocolonial authorities of Bamako. It thus expanded its audience with the goal of establishing a new regime based on its interpretation of Sharia law throughout the country.25 The United States has decided to increase its presence in Africa by invoking the threat of terrorism, establishing in the new African Command (Africom) in 2007. A diplomatic source revealed by Wikileaks, noted that the general headquarters should be based in Mali and that this would multiply the collaborative efforts—joint exercises, training managers, etc.—with African military forces, including those of Mali, within the framework of the “Saharan Partnership against terrorism.”26 So, on December 25, Obama announced a project for developing military cooperation with 35 African states, and on January 29, Niger revealed that it had accepted the establishment of a U.S. drone base. In reality, this beefed-up military presence is fundamentally intended to secure U.S. petroleum supplies (and other basic materials) shipped through the Gulf of Guinea, and to strengthen its position as it faces growing competition from China.

II. The importance of drug trafficking today—not only cocaine and heroin but also pirate brand name cigarettes—as well as illegal immigration passing through the Sahel to North Africa and Europe remains the subject of conjecture, although it seems established that they have experienced an increase in recent years with the proven assistance of large areas of state and local military units.

So, for example, in November 2009 an old Boeing 727 cargo plane—one of the few jets to have been able to land on a rapidly constructed airstrip—was discovered in the Malian desert, 200 kilometers north of Gao. Flying from South America, it had taken on cocaine for the French and Spanish markets, that had to be reached through Algeria and Morocco.

The Salafist fighting groups finance themselves by taking hostages and through trafficking in various commodities, which provides them money for arms. It was in this way that Mokhtar Belmokhtar, the presumed mastermind of the taking of the In Amenas hostages, Algeria, got the nickname “Mr. Marlboro.” This situation has led more than one observer—from Tariq Ramadan to the spokespeople for the French Army—to call into question the religious objectives of these groups. As for me, I don’t see why faith has to be opposed to profit and terror, though it is clear that popular Salafism is driven by other social dynamics than those nurturing al-Qaeda.

This imbroglio has led recently to the rise of numerous conspiracy theories attempting to divine what’s behind the multiplication of armed Islamist groups in the Sahel, attributing it to one or another of the traffickers, to the interests of the United States, or even Germany, to the dream of an independent Sahelian emirate, rich in natural resources, separated from the FrancAfrican states of Mali and Niger. So it was in the name of the “lesser evil” presumed to be French domination of the entire region, that Samir Amin last January 23 surprisingly justified Operation Serval (or Operation African Wildcat), the French military action in Mali.27 It seems that France will play the role of the policeman of the European Union in the Sahel, continuing to carry out the work of preparing and training and reorganizing the armies of Mali and of the Economic Community Of West African States (ECOWAS) that was decided last November at the instigation of France at a price of 12.5 million euros.28

What Does French Imperialism Want?

One month after the opening of the French military intervention, its success seemed to be complete: the principal cities of the North had been taken and only one French soldier had been killed in combat (though a few more died since then). The scope of civilian losses and destruction on the ground remain hard to estimate given the media blackout imposed by France. The Salafist armed groups have evaporated, avoiding a frontal attack. The Malian officials have greeted the troops from the old colonial power as liberators, with undeniable popular support. The reprisals carried out by the Malian Army or by elements of the self-defense militia have failed to tarnish the French success, and not the least of the miracles is having conferred on François Hollande a stature of a real chief of state. According to Le Parisien, Operation Serval won the approval of 75 percent of those polled. This “dream scenario” has begun to fracture with the first military difficulties in the Massif of Ifoghas, the multiplication of attacks, and the kidnapping of French nationals in Cameroon.

That said, the apparent success of the first phase of these operations poses a question: wasn’t there an overestimation of the firepower of the hardened and heavily armed troops who have fled before 2,000 French soldiers?29 How could France have the luxury of keeping the Malian Army completely out of the more sensitive conflicts, such as the taking of Kidal, which was captured without a struggle? How then can anyone believe that these Islamist groups were about to pounce on the center of the country before they had taken Bamako, the capital city with two million inhabitants who are violently hostile to them? Was the Malian army so unable to put up a fight against them? The Nouvel Observateur has revealed that, according to French intelligence sources, the Salafist fighters aimed at taking Mopti and its Sévaré Airport, while Captain Sanogo —the officer who staged a coup on March 22, 2012 — would profit by getting rid of interim president Dioncounda Traoré in Bamako. So that France, which had so far managed to cause problems for the putschists, notably through the pressures of ECOWAS, risked losing any credible political foothold in Mali. Its immediate response, prepared for in the field by Operation Sabre30 in September, would, on the other hand, give it time to work on site for a “democratic alternative,” duly sanctioned in good time by elections. It was only later learned that the Malian authorities had never asked for a ground engagement, but only for air support.31 Those who promised the French an Afghan quagmire, and praised the prudence of Washington and Berlin, went badly astray for the moment. On the other hand, the Malian and regional authorities—through the International Mission Support in Mali (MISMA), which involves seven countries of ECOWAS, but foremost Chad—will have to pay their debt in fighting the Salafist units that have retreated to the sands and mountains of Azawad. There are also constant comments on the upcoming installation of a French base in the center or north of the country: “It is not a coincidence,” noted one Senegalese commentator, “that the helicopter carrier Dixmude sailed from Toulon harbor to Dakar with a load as large as five TGV high-speed trains.”32 Such a base would be within easy reach of the uranium deposits of Arlit, and above all of Imuraren, that was won over at great cost by Areva at the expense of its Chinese competitors.33 It would complement the already existing bases of N’Djaména, Abéché (in Chad), and Djibouti on the Sahara-Sahelian frontier.

At the same time, Paris will without doubt maintain a heavily armed intervention force in Bamako in order to assure a political transition on its terms against the restive sections of the Malian Army. It could also well be that it would provide a limited degree of autonomy for the Tuaregs, which would explain why special units assigned to occupy Kidal have kept the Malian Army away and why the DGSE (the French intelligence service), which is already in contact with the MNLA—“diplomacy” actively supported by Switzerland—has worked to split the Salafist Ansar Dine. It seems in effect that the spokesman of this group, Mohamed Ag Arib, for a long time an émigré residing in France and known to the French Foreign Affairs Ministry, has played a key role in setting in motion the new Azawad Islamic Movement (MIA).

Will France be tempted to play the partition card in Mali, along the recent lines of Sudan, building on its privileged ties with key sectors of the Tuareg rebellion, a move it has been accused of by certain Malian political leaders? Nothing is less certain, insofar as it would put in danger the privileged links that it maintains with its principal neocolonial pawns in West Africa, beginning with Niger. Recall that the Common Organization of the Saharan Regions (OCRS), established by the French Fourth Republic in January 1957, aimed to bring the territories of southern Algeria, northern Mali and Niger, and western Chad, potentially rich in oil, under French administration during the war in Algeria and in the context of African decolonialization.34 In 1958, De Gaulle attempted to make the OCRS his numberone priority, with the explicit support of the Socialist Party (then the SFIO). This plan failed, however, due to the resolute opposition of the Sudanese Union-African Democratic Coalition (US-RDA) of Modibo Keïta, supported by the principal Tuareg chiefs.

If the Tuaregs were to drop some of the ballast of their claims for autonomy, they could be useful in putting pressure on the central government in Bamako, whose refusal to follow consistently the French line is a little out of place in the FrancAfrican landscape.35 From this point of view, sending UN peacekeepers to maintain peace between Bamako and the rebel movement of the North—the MLNA and the new MIA—could provide useful cover for France by leaving sufficient freedom of action—including military action—while giving the next Malian political leadership the veneer of international legitimacy.

The French bourgeoisie won a significant battle in West Africa, at least for the moment, not only at the expense of its Western and Chinese competitors, but also of the peoples of the sub-region, who will now be exposed to a new stage of the neoliberal agenda that Paris and the European Union promote without reservations. The serval cat is certainly small, but is said to be able to urinate twenty times per hour to mark his territory. To cope with this increased activism of French imperialism in Africa, it is high time that the left and Malian, African, and international social movements stop thinking in “less-evilist” geopolitical terms and develop an internationalist perspective that takes as its starting point the dynamics of social struggles. The solution to the crisis begins with the Malian refusal of exploitation of the country by foreign capital, whether French, European, U.S., Chinese, Algerian or Qatari and its local cronies. It assumes the unity of its peoples to defend their sovereignty around a social and democratic program that does not overlook the right to self-determination.

Footnotes

* This article is an expansion of an earlier contribution written in the heat of the moment titled "Mali : refuser la géopolitique du ‘moindre mal,’" which appeared in the Feb. 7 issue of the bimonthly Swiss newspaper solidaritiéS, also available at www.contretemps.eu.

1 Government of Mali and United Nations Development Fund report of Feb. 2006 on poverty in Mali (2001).

2 Fred Lauener, “Sahel : Les prix grimpent, la pluie manque et la famine s’installe,” (Caritas-Suisse), March 28, 2012 at www.cath.ch.

3 Cited by Jean Suret-Canale, L’Afrique noire, t. 1, Paris, Editions sociales, 1964. (Paul Vigné d’Octon [1859-1943] was a French anti-racist and anti-imperialist of the early twentieth century. French readers can find a review of two recent biographies here – translators note.)

4 “Médecine et colonialisme, ” in: Sociologie d’une révolution. L’An V de la révolution algérienne, (Paris : Maspero, 1972).

5 The future president of the Ivory Coast, Houphouët-Boigny appears to have been the first person to use the term “FrançAfrique,” to which he gave a positive connotation.

6 On the basic mechanisms inherited from colonization, see: Comité information Sahel, Qui se nourrit de la famine en Afrique ? Paris: Maspero, 1974.

7 On the life and political experience of Modibo Keita, see Modibo Diagouraga, Modibo Keïta, un destin, Paris: L’Harmattan, 2005.

8 Samir Amin, L’Afrique de l’Ouest bloquée, Paris, Minuit, 1973. In his current position as favoring French military intervention, Amin gives a more positive appreciation of the experience of Modibo Keïta, even alluding to “steps in the direction of economic and social progress [in Mali] as an affirmation of its independence and of unity among its ethnic groups.” (January 23, 2013.)

9 Howard W. French testifies to the sabotage of the Malian democratic experience in A Continent for the Taking. The Tragedy and Hope of Africa, (New York: Vintage Books, 2004).

10 The anthropologist and geographer Julien Brachet estimates their population at three million (Mediapart, Feb. 18, 2013).

11 For an in depth study of the conflicts of North Mali, see Baz Lecocq Disputed Desert. Decolonization, Competing Nationalisms and Tuareg Rebellions in Northern Mali, (Leiden: Brill, 2010).

12 After the Second World War, according to the French colonial administration, there were 50,000 Ikelan or Bella under the direct control of the Tuareg masters in the regions of Timbuktu and Gao (cf. Martin A. Klein, Slavery and Colonial Rule in French West Africa, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998). In the 1950s, the international press suggested that Tuareg chiefs were engaged in a traffic in black slaves sold in Saudia Arabia. (Bruce S. Hall, A History of Race in Muslim Black Africa, 1600-1960, Cambridge, Cambridge U.P., 2011).

13 It is known that slavery in Africa grew after the decline of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. (cf. Paul Lovejoy, Transformation of Slavery. A History of Slavery in Africa, 2nd ed., Cambridge, Cambridge U.P., 2000). Martin Klein estimates that at the beginning of the 20th century, under French domination, half of the inhabitants of Mali were subjected to some sort of servitude. (Slavery and Colonial Rule…).

14 Naffet Keita, L’esclavage au Mali, (Paris, L’Harmattan, 2012).

15 Bruce S. Hall, in A History of Race…, has shown that colonial France saw the Tuaregs as a “race” closer to white Europeans than blacks or even the Arabs.

16 Although this transit of arms cannot be exaggerated, it reflects the ambiguity of Algeria’s current policy with regard to Mali, amid simmering economic and political conflicts between the two countries, but it also reflects the manipulation of the Tuareg question by Algeria based on domestic considerations.

17 Especially in the irrigated area of the “Office du Niger,” downstream from Bamako, which is a legacy of colonization.

18 Mali is the second largest producer in West Africa, after Burkina Faso.

19 The Oakland Institute, Comprendre les investissements fonciers en Afrique. Rapport: Mali, 2011.

20 Since 2007 prospecting in the significant uranium deposits at Oklo in the Kidal region have been going on. It was expected that mining would begin in 2013.

21 The exploitation of the resources in this basin has already begun in Mauritania, notably under the leadership of the Total, Sonatrach (the Algerian state oil company), and Qatar Petroleum.

22 Survie Association, “Les zones d’ombre de l’intervention française au Mali, ” Dossier d’information, January 23, 2013 (www.survie.org).

23 A growing number of observers doubt the existence of a centralized structure corresponding to the initials AQMI (see notably, Mehdi Tage, “Vulnérabilités et facteurs d’insécurité au Sahel,” Enjeux ouest-africains, n°1 (August 2010).

24 The culturalist idea according to which the Tuaregs would have an ancestral allergic reaction to Salafism can’t withstand examination, nor can that according to which the secular Tuaregs movements are separated from their Salafist homologs by a firewall.

25 It seems that the Ansar Dine chief, Iyad Ag Ghali has had close relations with the Algerian secret services, who wanted to weaken the pro-independence positions of the Tuaregs.

26 Jean Nanga shows that this U.S. effort to penetrate West Africa militarily is now more than twenty years old, “Au Mali, une intervention néocoloniale sous leadership français, ” (cf., Inprecor, January-February, 2013).

27 One can read the position taken by Samir Amin and its relevant critique by Paul Martial on the Europe-Solidaire site (www.europe-solidaire.org/). On February 4, the Egyptian economist briefly responded to his critics, though without adding new arguments to the discussion (www.m-pep.org).

28 Survie Association, “Les zones d’ombre…”

29 As early as January 13, Philippe Duval showed that the Islamist peril had been greatly overestimated (www.tamoudre.org).

30 After two years, France deployed special forces, helicopters and a large arsenal to Burkina Faso and to Mauritania, a gesture reinforced last September by Operation Sabre (Survie Association, “Les zones d’ombre…”).

31 Vincent Jauvert & Sarah-Halifa Legrand, “Mali: histoire secrète d’une grande surprise,” Nouvel Observateur, February 7, 2013.

32 B. J. Ndiaye, “Mali : à quoi sert Serval ?” February 2, 2013 (www.nettali.net).

33 The military coup d’état that overturned Nigerian President Tandja Mamadou in April 2010, is probably not unrelated to the conflict, which in 2007, with the opening of the uranium deposits, pitted France against the Chinese and Indian investors.

34 A similar project was broached in 1951 in the monthly Hommes et Mondes, before becoming a subject of parliamentary debate in France in 1952 (Hall, A History of Race …). It was finally abandoned after Algerian independence, in 1962.

35 In January 2009, the Malian authorities refused to sign an agreement with Paris on the readmission of Malians without legal status in France.