Kiddin’ on the Square

In October 1969, pianist/ singer/composer Mose Allison recorded “Monsters of the Id.” At a time when recent history had witnessed a police riot at the 1968 Democratic Party Convention, the police crackdown on protesters at Berkeley’s People’s Park, and popular backlash against anti-war, New Left, counter-culture, and Black Power sentiment, Allison began by warning that the title characters no longer remain hidden, but have come out in full view. To the accompaniment of a slightly discordant horn section, Allison—singing in his characteristic style, with its idiosyncratic pauses and accents—spins a variety of often ghoulish metaphors that remain just as timely in today’s era of Tea Party, torture reports, Stand Your Ground, and Donald Trump: “They’re sprouting through the cracks … They’re deputizing maniacs / Creatures from the swamp rewrite their own Mein Kampf.”

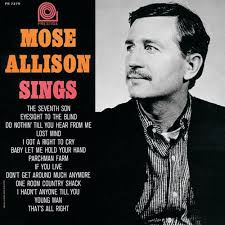

By the time Allison recorded “Monsters of the Id,” he had been on the music scene for more than ten years, and, though commercial success largely eluded him, he had gained a devoted following on the basis of his jazz persona and his witty, literate, and sardonic lyrics (who else, for instance, would write a love song titled “Your Molecular Structure” with phrases like “Your molecular structure is really something swell / A high-frequency modulated Jezebel”?). Born in 1927 in Tippo, an unincorporated town on the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta, Allison had grown up on the white side of the Jim Crow line. After a stint in the military and graduating from Louisiana State University with a degree in English, Allison migrated to New York City in the mid-fifties, where he worked backing up such jazz luminaries as Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, and Stan Getz. Immersing himself in the New York jazz scene while holding tight to his southern roots, Allison ultimately would craft a style reflecting a capacious range of influences, including such jazz musicians as Lester Young, Erroll Garner, and Thelonious Monk; blues singers Percy Mayfield and Muddy Waters; popular performer Nat King Cole; composers Bela Bartok and Charles Ives; and literary figures like Kurt Vonnegut and Louis-Ferdinand Celine.

Allison cut his first album as leader of his own trio, Back Country Suite, for Prestige Records in 1957. Inspired by the pastorales of such composers as Duke Ellington, Igor Stravinsky, and Aaron Copland, Allison strung together nine instrumentals and one vocal track portraying southern life, fusing the earthy vernacular of the Delta blues with the brio and sophistication of modern jazz. As Allison’s biographer, Patti Jones, points out in One Man’s Blues: The Life and Music of Mose Allison (London: Quartet Books, 1995), it was rare for a white musician to play the country blues in this era when the modern civil rights movement was in its infancy and the folk and blues revival of the sixties would not arrive for several years—two years, even, before Samuel B. Charters’ pioneering study, The Country Blues—especially a musician who “was earning impressive credentials in New York City as an accomplished pianist in the modern jazz idiom, a more sophisticated musical style harmonically, melodically, and rhythmically.”

The one vocal track on Back Country Suite is titled simply “Blues,” though it would later come to be called “Young Man Blues.” In his conversational voice, Allison sings a lament for the lost status of youth, with its strength and virility, and the pre-eminence of age and wealth: “Well a young man ain’t nothing in this world these days”—voice unaccompanied, like nothing so much as a field holler, before the piano comes in. Beginning with this simple line, a generation of younger American writers and musicians would take note first of the music’s energy and vitality and then, often much later, the discovery of the performer’s race. In Richard Farina’s early-countercultural novel Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me (1966), set in 1958 in an Ivy League school, protagonist Gnossos Pappadopoulis complains when he comes into his dorm room and finds his friends listening to Dave Brubeck. “Burn that Brubump crap, man, I’ve got new sounds. What are you doing, starting a Mickey Mouse club or what?” Gnossos hands Back Country Suite to Heff, his black roommate, who says, “Who’s Mose Allison? … Never heard of him. … An’ I don’t dig names like Mose … . It’s Uncle Tomming.” “He’s white, baby,” Gnossos replies. “Don’t lose your cool.”

Similarly, science fiction writer and television critic Harlan Ellison would write in 1969 that the “biggest aural shock of my life … was finding out, about ten years ago, that Mose Allison was white.” Blues singer John Hammond reflected his similar experience in Los Angeles in 1962, having heard Allison on record: “I imagined him to be a black guy from Chicago or Memphis. An old-time blues-singer guy. Was I ever surprised when I walked … [into] the Lighthouse and saw Mose Allison, a white guy, playing in this club.” As Allison would remember, even Muddy Waters was surprised on their first meeting, having assumed Allison was black.

If anything, Allison made a bigger impact on British musicians. Pete Townshend, for instance, would describe visiting an American friend living in London in 1963, who pulled Back Country Suite from his sizable record collection. “The man’s voice was heaven,” The Who’s guitarist recalls. “So cool, so decisively hip, uncomplicated and spaced away from the mainstream of gravel-voiced Delta bluesmen.” Then, when his friend showed Townshend Allison’s photograph, Townshend continued, “‘He’s fucking white!’ I scream. A real, cool, relaxed, genuine, funky, hipped out, WHITE hero.” Former Rolling Stone Mick Taylor would remember, “If you were British playing the blues in the 1960s, you were influenced by Mose Allison.” As testament to his influence, a wide range of musicians have covered Allison’s songs: American performers like Johnny Rivers, Bobbie Gentry, Bonnie Raitt, and Chris Spedding and bands like Paul Butterfield’s Better Days, Hot Tuna, Blue Cheer, and even the Spiders—the band that would evolve into Alice Cooper; British bands and performers like The Who, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, The Yardbirds, Elvis Costello, and the punk band The Clash. Former Cream bassist Jack Bruce backed Allison on the live album Lessons in Living (1982); Van Morrison, Georgie Fame, and Ben Sidran released a tribute album, Tell Me Something: The Songs of Mose Allison (1996); and American singer/songwriter Greg Brown recorded a 1997 homage, “Mose Allison Played Here.”

Allison’s crossing of racial boundaries—in his music, his voice, his name—embodies what jazz critic Albert Murray terms “the incontestably mulatto” nature of American culture. But Allison realizes this whole concept is problematic, based as it is on a large degree of white appropriation of African American culture, a topic Allison would satirize in his 1989 song “Ever Since I Stole the Blues”: “Well the blues police from down in Dixieland, tried to catch me with the goods on hand / They broke down my door but I was all smiles, I had already shipped them to the British Isles.”

The opposition between black and white represented only one of several boundaries Allison worked to break down throughout his career. His entire oeuvre focuses on merging such opposites as southern/northern, rural/urban, highbrow/popular. As he explained in 1962, “I’ve always figured that you’ve got to be able to assimilate what normally seem to be opposing elements. That’s the way reality is.” He has ignored the boundaries of musical genre (and in the process, given fits to the marketing departments of his various record companies). His music reflects the polyglot diversity of American culture, a fact demonstrated by the wide range of songs he has covered—including jazz by Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie; country by Hank Williams and Lefty Frizzell; blues by Percy Mayfield, Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, and Willie Dixon; and such standards from the Great American Songbook as “St. Louis Blues,” “When My Dream Boat Comes Home,” “The Tennessee Waltz,” and “You Are My Sunshine” (the last of which Allison presents in a mournful rendition much more in keeping with the song’s lyrics than more upbeat, popular versions).

As an example of his defiantly pluralistic fusion of various cultural traditions, Allison spent several years in the early seventies listening to classical piano sonatas as well as modernist composers like Elliot Carter and avant-garde jazz pianist Cecil Taylor in an attempt to improve his ability to play—and improvise—with his left hand. “Today,” he commented in 1974, “I’m not so dependent on the one-handed bop style I used for quite a while.” Allison also is a student of world music, arguing that all music can be broken down into a small number of categories. “In fact,” he has said, “there’s only three kinds of music: Bach, the blues, and Schoenberg. Bach is linear, melodic; Schoenberg is new sounds, twelve-tone harmony; and a universal blues is played in every country. Everything else is a mixture of those three elements to a certain degree.” As for the blues, “All societies have something akin to the blues. There’s a universal lament that’s interchangeable with country blues, and I’m real interested in that. … I went to a Chinese opera one time in San Francisco and there was an old guy who sounded just like Lightnin’ Hopkins to me. They were essentially singing blues harmonies.”

Drummer and occasional Allison accompanist Billy Cobham has described what he calls Allison’s “American folkloric proletariat connection.” To a large extent, this vision grows out of Allison’s working-class view of his work, based on his relationship with his various record companies. Allison’s first record contract, with Prestige, required him to produce six records in two years, paying him only $250 per record. The contract was fairly standard for its era, though as Allison’s biographer Patti Jones comments,

From the artist’s perspective, flooding the market with an overabundance of material, especially if musically inconsistent, could only be damaging to the consumer’s perceptions of the artist’s work. More significantly, the notion of a new, developing recording artist being legally obligated to deplete his or her catalog quickly, producing music in assembly-line fashion, is a short-sighted practice militating against long-term success. Unless the artist is naturally prolific, mass production often results in a burn-out that destroys the creative process, taking the artist’s career with it.

His next record company, Atlantic, pushed Allison to record more commercially accessible music. “They kept sending me all this Gene Autry material,” he said. “They wanted to make a pop singer out of me.” By the seventies, Atlantic was pressuring Allison to add back-up singers and a disco beat.

Making no money off his own records, Allison survived through songwriting royalties and incessant touring. In the eighties, he typically played 220-230 nights a year, a lifestyle he wryly commented on in such songs as “The Getting Paid Waltz” (1989), “Cabaret Card” (1994), and “Nightclub” (1971): “Been working in nightclubs so long, can hardly stand the break of day / Run-down rooms and bad pianos, but it’s still the only way.” In his mocking narrative on his own lack of commercial success, “Gettin’ There” (1987), he laments, “If I was selling fantasy, I’d be a millionaire / But I’m not disillusioned … But I’m getting there.”

In the late sixties, Allison wrote “Top Forty,” a blistering satire of the commercial style of music Atlantic wanted him to produce (though he did not record it until 1987): “When I make my top forty, big beat rock and roll record everything is gonna be just fine … / No more philosophic melancholia, eight hundred pounds of electric genitalia.” Allison rejects accusations of cynicism, though, saying in a 1986 interview, “To me, the most cynical musical experience of this century is when you get four self-indulgent young millionaires together and they tell everybody all they need is love.”

The black humor and ambivalence running throughout Allison’s work reflects the literary influence of writers like Kurt Vonnegut. Lyrics like “I don’t worry about a thing, ’cause I know nothing’s going to be all right” grow out of his conviction that “ambivalence is just where we are. The universe is built on the interaction of opposing forces. You’ve got to learn to live with that. You have to be able to entertain opposing ideas at the same time.” The darkly humorous world view is summed up in the title of his 1982 song, “Kiddin’ on the Square,” which he says is “one of my favorite street sayings; doesn’t seem to be in use anymore and probably needs explaining. It could be paraphrased as ‘jivin’ for real’ or joking with serious intent—sounds like someone I know.” For instance, Allison presents a droll take on the apocalypse in “Ever Since the World Ended”: “Dogmas that we once defended no longer seem worthwhile / Ever since the world ended, I face the future with a smile.”

Allison’s blues sensibility provides a vehicle for his social and political commentary. As he has said, “So much of the country blues is innuendo and disguised comment. You really have to know the jargon to be able to get through. In other words, the plantation blues were the oppressed saying it right out in front of their tormentors, and the tormentors didn’t even pick it up.” In his own work, Allison rarely sings about specific topical issues, giving his commentary more universal relevance. His 1962 song, “Your Mind Is on Vacation,” could just as easily describe our current crop of political pundits and talk-radio hosts: “If silence was golden, you couldn’t raise a dime / Because your mind is on vacation and your mouth is working overtime.”

“Everybody Cryin’ Mercy,” recorded in the summer of 1968, makes oblique reference to the contemporary situation of war, assassinations, and racial rebellion, but remains timeless in its commentary: “People running ’round in circles, don’t know what they’re headed for / Everybody cryin’ peace on earth, just as soon as we win this war.”

Innuendo and indirection do not make Allison’s lyrics less pointed. His 1971 song “Western Man,” for instance, is a two-minute-and-forty-second history of imperialism. “Western man had a plan, and with his gun in his hand / Free from doubt, went right out on the world.” “Big Brother,” written in the late sixties, remained just as relevant when he got around to recording it in 1989 (and equally so in today’s world of NSA spying and Citizens United): “Don’t say nothing bad about a CEO … / I only tell you ’cause it’s true, Big Brother is watching you.”

Allison takes more direct aim at modern celebrity culture in “Who’s In, Who’s Out” (1993): “Let’s all get excited about the party to which we’re uninvited,” and the competing priorities of consumer culture in “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” (1989): “Do I show my concern for the needy, for the folks who are living outside / Or am I just plain greedy, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” “The More You Get” (1997) focuses on the fundamental insecurity of acquisitive consumerism—“The chance to make money is hard to refuse / But the more you get, the more you got to lose”—while “Numbers on Paper” (1997) highlights the dehumanizing nature of capitalism: “Numbers on paper, designate your ration / In or out of fashion, world beyond compassion.”

In a career spanning more than sixty years, Allison has confronted not only his own commercial irrelevance, but also his own aging. And like everything else, he has done so with his typical ironic humor. “Certified Senior Citizen” (1994) warns, “You may ignore me, but doctors adore me. … You don’t like my drivin’, I don’t like your jivin’”—while “My Brain” (2010) offers the reminder, “My brain is losin’ power / twelve hundred neurons every hour.” Most poignantly, in 1997 Allison offered a redux of his original vocal performance with “Old Man Blues.” Forty years after bursting on the scene lamenting the lost status of the young man, Allison now portrays the cultural logic of consumer capitalism shifting power to youth, with its sex appeal and purchasing power, while marginalizing the elderly: “Well an old man ain’t nothing in the USA.” And thus Allison brings the story full circle. But is the man serious?

Nah, he’s just kiddin’ on the square.