Introduction to Articles on the Climate Crisis

In August 2021, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—the UN-sponsored body that brings together the world’s leading climate scientists—issued its latest report on what is happening to the world’s climate. We have known for decades that increased emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases have already led to a dangerous increase in the average surface temperature of the planet, which is now more than 1° Celsius hotter than in the pre-industrial period. Even that amount of global warming has already had severe consequences in terms of more extreme weather events, unprecedented heat waves and forest fires, the melting of the polar ice caps and rising sea levels, the large-scale disruption of ecosystems and rapidly increasing rate of extinction, and other dire consequences. The new report confirmed in meticulous detail that humanity is facing an existential crisis, since if current trends continue, the conditions for the physical survival of human society will be undermined. Atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide were at 280 parts per million (ppm) before the industrial revolution. Today they have reached 415 ppm. If emissions continue at their current level, atmospheric carbon dioxide will climb to 560 ppm by the end of the century, resulting in a temperature increase of 3°C, far above the 1.5° that governments around the world have agreed is the maximum increase to prevent the consequences spiraling out of control. If emissions increase, climate catastrophe will arrive even sooner.

In August 2021, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—the UN-sponsored body that brings together the world’s leading climate scientists—issued its latest report on what is happening to the world’s climate. We have known for decades that increased emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases have already led to a dangerous increase in the average surface temperature of the planet, which is now more than 1° Celsius hotter than in the pre-industrial period. Even that amount of global warming has already had severe consequences in terms of more extreme weather events, unprecedented heat waves and forest fires, the melting of the polar ice caps and rising sea levels, the large-scale disruption of ecosystems and rapidly increasing rate of extinction, and other dire consequences. The new report confirmed in meticulous detail that humanity is facing an existential crisis, since if current trends continue, the conditions for the physical survival of human society will be undermined. Atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide were at 280 parts per million (ppm) before the industrial revolution. Today they have reached 415 ppm. If emissions continue at their current level, atmospheric carbon dioxide will climb to 560 ppm by the end of the century, resulting in a temperature increase of 3°C, far above the 1.5° that governments around the world have agreed is the maximum increase to prevent the consequences spiraling out of control. If emissions increase, climate catastrophe will arrive even sooner.

The one ray of hope in the IPCC report is that the increase in global temperature can still be held to 1.5°C if we rapidly reduce fossil fuel use. That reduction would require implementing an immediate transition from the use of coal, natural gas, and oil to renewable energy sources (in particular, solar and wind power) that would have to begin immediately and be completed no later than 2050. This should have been the agenda at the COP26 climate negotiations in Glasgow, Scotland, this past November. But while the assembled political leaders paid lip service to the severity of the crisis, the agreements they reached fell far short of what needs to be done. The pledges made by the world’s leading economies to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions are not nearly sufficient, and with past behavior as a guide to what will happen in the future, we know that even these inadequate pledges will not be met. Perhaps nothing better illustrates the irrationality of capitalism than its failure to produce serious solutions to the imminent danger of climate disaster.

The articles in this section examine different aspects of the climate crisis. In his essay, Martin Hart-Landsberg takes up the question of how a rapid transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy could take place. He draws parallels with the very different transition that took place in the U.S. economy at the beginning of World War II. While this transition was to a massive increase in military production, Hart-Landsberg argues that there are valuable lessons to be learned. This history certainly demonstrates that even a huge economy like the United States can be fundamentally restructured in a very short period of time. The mechanisms that were used to bring this transition about may provide ideas about how a Green New Deal that shifts the economy to the use of sustainable energy sources could be implemented.

In their contribution, Laura Schleifer and Daniel Fischer focus on the question of animal agriculture, which is itself a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. While individual lifestyle changes will not solve the climate crisis, there is little doubt that creating a just and sustainable economy will require significant changes in how people in the world’s richest countries live, including major changes in diet. Meat consumption on the level that currently takes place in the United States and similar countries is unsustainable. There are also strong health and ethical arguments for reducing or eliminating such consumption and radically changing the way in which humans treat the rest of the living world.

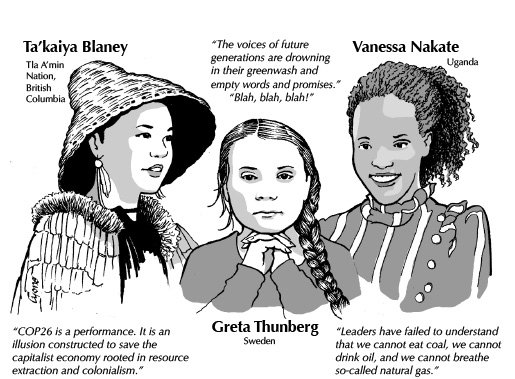

But how can the changes that we need come about while they are opposed by the fossil-fuel industry, agribusiness, and other powerful capitalist interests? Radical change has always required powerful movements from below. While the COP26 talks did not produce significant solutions from world leaders, it did provide an opportunity for activists from around the world to continue building a grassroots network committed to radical change. On November 6 in Glasgow, a coalition of environmental organizations led a march of over 100,000 people, demanding system change, not climate change. It will require an even bigger movement to force governments to move in the direction that is needed. This will require large-scale disruptive actions—including school walkouts, civil disobedience, and mass strikes—that will make the cost of continuing business as usual higher than the cost of agreeing to change. Youth activists around the world, such as Ta’kaiya Blaney, Vanessa Nakate, and Greta Thunberg, have played an outstanding role in building such a movement. It will also need the strength of organized labor if it is to succeed. The protest in Glasgow was led by Scottish union members. In his contribution to this section, Steve Ongerth examines the possibility of building a green union movement that will play a leading role in fighting climate change.

The fight against climate change ultimately requires not just changing a few policies, but taking on and transforming the entire economic system, replacing capitalism with a sustainable ecosocialist future. The articles in this section only take on some of the many questions that this raises, questions to which we will surely return in future issues of New Politics.