Green Is the New Green: Social Media and the Post-Election Crisis in Iran, 2009

The Persian language blogosphere is rich, varied, and dynamic. Of the 100 million blogs registered around the world in 2005, 700,000 were Persian language, either inside Iran or in the diaspora. Of these, over 60,000 are updated frequently. With over 20 million Iranians connecting to the internet, and over 600,000 Iranians signed up on Facebook by the presidential election of the summer of 2009, the Iranian cyber community is by far the most dynamic such community in the Middle East, and one that is unambiguously diverse. Of the 60,000 Persian language blogs, 75 percent may be characterized as non-political in content, interested rather in questions of religion, poetry, and sexuality.

Shortly after Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s election as president of Iran in June 2005, there was a definite move towards the centralization of power over traditional media. During the first two years of Ahmadinejad’s presidency, more than 100 newspapers and other periodicals were banned. 70 percent of press outlets were run by active supporters of Ahmadinejad. On the eve of the June 12, 2009, presidential election, foreign reporters were either imprisoned or expelled from Iran. And then, in the aftermath of the election, what remained of the opposition’s news outlets was banned or put under strict surveillance. This in part led to the rise of online “underground” papers, such as Kalam Sabz (Green Word) and Khiaban (The Street), and more urgent uses of social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and the Iranian social media site, Balatarin.com.

According to Nasrin Alavi, Gholamhossein Karbaschi (the vice presidential candidate on the ticket of reformist Mehdi Karroubi in the presidential election of 2009) was the first Iranian on Twitter to call the presidential election of June 12, 2009, a fraud. He was by no means the last. Elham Gheytanchi describes the days following the election:

Immediately after the results of the election were announced showing Ahmadinejad’s “landslide victory,” protesters poured into the streets. For three consecutive days, masses of Iranians marched peacefully onto the streets in silence asking one question written on their placards: “Where is my Vote?”

As the results of the election were announced, a twitter message from Bandar Abbas, a port city in the south of Iran, read Raye ma ra dozdidand, bahash darand poz mida (“They have stolen our votes and they are flaunting our stolen votes!”)

In an unprecedented move, the political establishment decided to cut all SMS [text] messages, the Internet connections and mobile phones in the week after the election results were announced. The next day, demonstrators in at least 20 different locations in Tehran gathered, waving placards that read Doroghgoo khaen ast va khaen tarsoost va tarsoo sms ghate mikonad (“The Liar is a Traitor and the Traitor is fearful and the fearful cuts the SMS.”)

As news and images of the protests on the ground circulated in social media all over the internet — on Flickr, on Twitter, on YouTube, and on Facebook — they were channeled back to Iran via satellite, broadcast largely by way of the then-popular BBC Persian.

A sense of euphoria and unprecedented freedom had dominated national politics during the presidential campaigns. Election activities were color-coded. And campaign paraphernalia, campaign headquarters, and campaigners themselves were clearly differentiated using pre-designed graphic coding based on the colors of the candidate’s campaign. Indeed, people spoke of Tehran in campaign colors. Iranian state-owned television broadcast a series of lively debates among the candidates. This was a first under the Shi’a theocracy. During one of the debates, the reformist candidate Mir-Hossein Moussavi put on a green shawl to highlight his status as a descendent of the prophet Muhammad. A month later, in the days following the election, an all-embracing, spontaneous movement donning green armbands, finger-bands, and headbands took to the streets to call Ahmadinejad’s victory a fraud — the color green thus became the symbol of the movement. The opposition was lovingly called the “Sea of Green,” the “Green Wave,” or the “Green Movement.”

The silence of the street protesters was broken as the violence of the regime became palpable. Neda Agha Soltan was brutally shot and murdered on Kargar Avenue, at the corner of Khosravi and Salehi streets in Tehran on June 20, 2009. The YouTube video documenting her death in the midst of a small crowd circulated on Facebook and Twitter immediately. Her name, Neda (“voice” or “calling” in Persian), became the rallying cry for the Iranian opposition. Images from the street protests showed men and women, urban and rural, young and old, marching shoulder to shoulder, mourning the disunity that had gripped the nation.

Outside Iran, around the globe, images of the spectacular crowds in green and the murder of Neda Agha Soltan captured the hearts and galvanized the will of people of all backgrounds and ages. High school students in the United States would talk about “Going Iranian” against authority figures. Journalists like Roger Cohen who had been forced to leave Tehran immediately after the election, felt bereft and wrote about “the responsibility of bearing witness.” Indeed, as Golbarg Bashi noted in the heat of the summer, “Iranian is the new black.” Hundreds of songs dedicated to Neda, in English and in Persian, started circulating on YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. Her name became a search topic or so-called “hashtag” on Twitter (#Neda). It was the highest ranking hashtag on June 20, 2009, indicating thousands of posts on the day of her death.

A corollary hashtag, #iranelection, continues to rank on Twitter. It was the highest ranking hashtag for weeks following the elections, dropping only momentarily after the death of Michael Jackson. It ranked high as a search topic on the 30th anniversary of the hostage crisis, November 4, 2009, and on the 31st anniversary of the Islamic Republic on February 11, 2010.

It may come as no surprise, then, that thousands of people on Twitter around the world put a green overlay on their avatars — the two-dimensional icons used to represent themselves — in solidarity with the Sea of Green in Iran. Many changed their location to Tehran and set their time zone to +03:30 GMT to protect the identities of people who were actually tweeting from the ground. This image of a Neda with a green overlay — a Neda Soltan who was initially mistaken as the murdered Neda Agha-Soltan — is made up of the many thousands of green avatars of active Twitter subscribers in the aftermath of Iran’s summer elections (Neda Soltan is currently seeking asylum in Germany in the wake of the publicity that the misuse of her image attracted.)

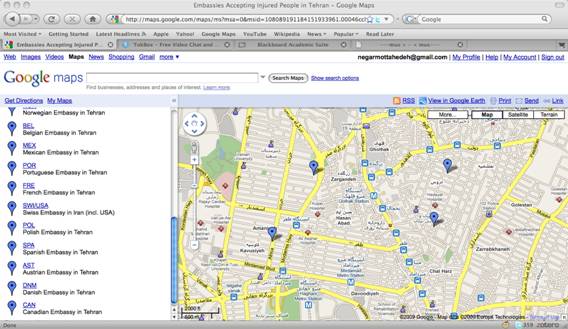

In the absence of foreign news agencies and independent media in Iran, these thousands of supporters of the Sea of Green on social media became nodal points of information for what was happening on the ground. On the 31st anniversary of the Islamic Republic, all internet access and SMS was cut in Iran. Citizen journalists, young and old, reported on the crowds, on the slogans, and on the violence of the police in Tehran during the protest by calling in to Epersian radio, which then broadcast the news all over the world online. Their reports were translated, transcribed, and broadcast immediately by Twitter and Facebook subscribers, reaching millions of people all over the world, long before news broke on broadcast television. Many supporters continue to help spread the news about various online and in-person campaigns. In the early days of the protests, many also came to the aid of Iranian protesters by identifying safe havens for the wounded on Google maps as word spread that the wounded were being picked up and imprisoned by military forces upon their arrival at hospitals around Tehran.

“Social media: It’s like the phone turned into a radio,” writes Clay Shirky. In fact, it is precisely this broadcast model of social media, combined with the intimacy of texting, that allows personal experience to resonate deeply both locally and globally. This, combined with the fact that we are privy to the everyday life of others on social media who live remote from us in every other way, creates a unique connection of trust and solidarity between activists on the ground and activists on social media, a winning formula for the Sea of Green.

On December 7, 2009, about 6 months after the presidential election, Majid Tavakoli, a student at Tehran’s Amir Kabir University of Technology, was arrested after he gave a talk during the student protests. A photograph of him in a hijab (full Islamic veil) was published by official news agencies announcing that he had attempted to flee security forces donned in women’s clothing. Supporters of the Green Wave around the world saw things differently. Cognizant that this photograph was an attempt to ridicule Majid Tavakoli, by associating his courage with “the weaker sex,” thousands of Iranian men all over the world donned the hijab and posted their photos on the web, using these photographs as their avatars on social media, such as Twitter and Facebook.

In captioning their photographs, the men claimed their solidarity with Iranian women who have no choice but to veil under the Islamic regime; they voiced their opposition to the human rights violations of the Islamic Republic and called for the release of the imprisoned Majid Tavakoli. This global campaign came to be known as the “The Men’s Scarves Movement” or the “I am Majid” campaign, receiving the hashtag #IamMajid on Twitter.

The international campaign eventually went live. A YouTube recording signaled its impact elsewhere: A group of Iranian men calling themselves “Majid” posed together, donning the hijab in front of the Eiffel tower.

This act of resistance to the violation of human rights in Iran had stunning reverberations: French men and women donned the veil in solidarity with the Iranian men’s scarves movement, and in this simple gesture, that went viral on the internet, showed their opposition to l’affaire du voile in France (the controversy in France over the wearing of veils in public).

This is not to say that the effort to bring about civil rights and the firm stand against the violation of human rights in Iran has subsided in any way on the part of the Green Movement, but to suggest that the circulation of the images and sounds of the post-Election period, their going viral on the internet, has had important consequences for oppositional movements and global collaborations elsewhere.