Great Power Rivalry in the Early Twenty-first Century

One of the most important issues of our time is the intensifying rivalry between the imperialist Great Powers: the United States, China, the EU, Russia, and Japan. Diplomatic rows, sanctions, trade wars, military tensions, and, ultimately, major wars now loom as prominent features of the historic period now unfolding. Trade war between the United States and China, tensions in the South China Sea, sanctions between the West and Russia? The prospect of Great Power rivalry has already become the present.

One of the most important issues of our time is the intensifying rivalry between the imperialist Great Powers: the United States, China, the EU, Russia, and Japan. Diplomatic rows, sanctions, trade wars, military tensions, and, ultimately, major wars now loom as prominent features of the historic period now unfolding. Trade war between the United States and China, tensions in the South China Sea, sanctions between the West and Russia? The prospect of Great Power rivalry has already become the present.

Many on the left fail to grasp the essence of this key development of world politics or to draw the necessary conclusions. The author of these lines has recently published a comprehensive book on this subject called Anti-Imperialism in the Age of Great Power Rivalry.1 In this article I will summarize some of the main findings of my analysis with a special focus on the economic bases of the rivalry between the two largest states—the United States and China.

In the past period, and in particular, the last decade, we have seen a dramatic shift in the economic and political balance of forces between the major imperialist powers. The old, Western powers—in particular the United States—have faced a decline that’s reciprocal to the rise of new imperialist powers—China and Russia. I will demonstrate this by analyzing a number of key indicators.

Production and Trade

As was discussed in an article published in this journal five years ago, China has become the most important challenger to America’s status as the hegemonic imperialist power.2 China’s rise, as well as the decline of the United States, has not evened out nor abated in the interim. Both are in a state of sustained acceleration.

When we look at the basis of capitalist value production—global industrial production—we see that the United States’ share decreased from 25.1 percent (2000) to 17.7 percent (2015); Western Europe’s share also declined from 12.1 percent to 9.2 percent, while China’s piece of the world pie exploded from 6.5 percent (2000) to 23.6 percent (2015).3

Likewise, while the United States’ share in international trade declined from 15.1 percent (2001) to 11.4 percent (2016), China’s share rose in this period from 4.0 percent to 11.5 percent.4 According to the latest statistics published by the World Trade Organization, China’s share in merchandise trade in 2017 was 11.5 percent while the United States’ was 11.1 percent.5

Such a decline of the old, Western imperialist powers and the emergence of China as a new challenger can be observed not only within the scope of the raw numbers for capitalist value production and trade. We see the same development reflected when we analyze the national composition of leading capitalist monopolies on the basis of corporate data.

Global Corporations

Comparing the Forbes Global 2000 list of the world’s largest corporations for the year 2003 with the year 2017, we see that while the United States presently remains the strongest national power, its share has declined substantially, from 776 corporations on the list (38.8 percent) to 565 (28.2 percent). In the same interval, China’s share grew dramatically. It now ranks as number two: from only 13 corporations (0.6 percent) on the Forbes list to 263 (13.1 percent). Japan’s share declined in this period from 16.5 percent to 11.4 percent; Britain’s share fell from 6.6 percent to 4.5 percent, and Germany’s share sank from 3.2 percent to 2.5 percent.6

We see the same picture when we compare the regional composition of the world’s top 5,000 companies (by market capitalization) for the years 2000 and 2016. Given the larger number of monopolies, this statistic is even more representative of the dramatic change that has taken place in the power relations between imperialist rivals. China’s rise is confirmed again. In 2000, its share among this list of leading corporations was 402 (8.0 percent). In 2016, this share had grown to 1,085 (21.7 percent). North America’s share declined from 1,958 (39.2 percent) to 1,519 (30.4 percent). Europe’s share shrank from 1,346 (26.9 percent) to 876 (17.5 percent), and Japan’s share fell from 659 (13.2 percent) to 437 (8.7 percent).7

Another study, published by the UN Conference on Trade and Development, also confirms China’s rise as home to many of the biggest global monopolies. It reports that China’s share among the largest 2,000 transnational corporations (TNCs) has grown so massively in the past two decades that by 2015 Chinese firms took 17 percent of all profits in this group of largest enterprises. The UNCTAD report adds, “Interestingly however, the share of Chinese financial TNCs in top TNCs’ profit expanded rapidly to more than 10 percent to total top TNCs profits, exceeding those of United States’ financial top TNCs in 2015.”8

These figures prove beyond doubt that China’s rise (and the West’s decline) is not limited to production and trade. Some left-wing academics have attempted a denial of China’s imperialist character by claiming that the Middle Kingdom’s status is restricted to that of the global workbench. But this is an old paradigm. China not only produces and trades a significant share of global capitalist value—it also owns a large share of it. This is reflected in the substantial portion of Chinese corporations among the world’s top monopolies as well as the volume of their profits (in both the industrial and the financial sectors). In other words, Chinese corporations (even if they are formally state-owned) are not “socialist” mega-enterprises but truly capitalist monopolies.

Billionaires

Another example, revealing much about China’s supposed “socialism,” is the rise of the billionaires. China has become home to the largest number of billionaires, or the second largest—depending on which list one takes—in the world. According to the 2017 issue of the “Hurun Global Rich List,” 609 billionaires are Chinese. By comparison, 552 are U.S. citizens. Together they account for half of the billionaires worldwide.9 The Forbes Billionaire List (which is United States-based while Hurun is China-based) sees the United States as still ahead. According to Forbes, “the U.S. continues to have more billionaires than any other nation, with a record 565, up from 540 a year ago. China is catching up with 319. (Hong Kong has another 67, and Macau 1.) Germany has the third most, with 114, and India, with 101, the first time it has had more than 100, is fourth.”10 While the details vary, the underlying trend remains the same: The weight of China’s monopoly capitalists is increasing.

Very similar results emerge from the latest edition of the annual Billionaires Insights report, published in October 2018 by the Swiss bank UBS jointly with Britain’s PwC, a financial services firm.11 According to this report, there are 2,158 billionaires in the world and 373 have their home in China. This figure rises to 475 if we add the billionaires living in Hong Kong and Macao (both jurisdictions are part of the Chinese state), as well as Taiwan. This means that about one-fifth of the global super-rich—that is, the monopoly capitalists—live in China! This is not far below the number of billionaires living in the United States (585) and above the figures for Japan as well as the combined totals for all the imperialist powers in Western Europe (414). Furthermore, it was the Chinese billionaires who experienced the fastest wealth growth in 2017 (39 percent). Billionaires in other countries had much lower growth rates (the global average growth was 12 percent). China is also the country with the highest number of new billionaires: 106 people became billionaires in 2017 (although a number dropped off the list from 2016). That comes out to roughly one new billionaire every three days.12

It is evident that the Chinese capitalist class has experienced the fastest growth in the world in the past decade. The UBS/PwC report comments, “Twelve years ago, the world’s most populous country was home to only 16 billionaires. Today, as the ‘Chinese Century’ progresses, they number 373, nearly one in five of the global total.”

China’s transformation is also reflected in the growing number of millionaires and billionaires among its parliamentarian deputies. The Hong Kong-based daily newspaper South China Morning Post (SCMP) recently published a very interesting report about the wealth of China’s lawmakers.13 The paper is known as a serious source, and it certainly knows what it’s talking about, as it is owned by the Alibaba Group, a Chinese multinational technology corporation headed by Jack Ma, one of the wealthiest people in the world.

This article reports that out of the 5,000 delegates in China’s legislature, 93 are dollar-denominated billionaires. (Unfortunately, the report does not tell us how many of China’s lawmakers are millionaires, but the figure obviously must be substantially larger.) These dollar-denominated billionaire lawmakers have an accumulated wealth of US$504 billion!

The SCMP adds,

By comparison, the 50 richest members of the U.S. Congress had a combined wealth of US$2 billion in 2016, according to Roll Call’s data. Darrell Issa, co-founder of automobile-components maker Directed Electronics and a Republican Representative from California, was the wealthiest congressman that year, with a net worth of US$283.3 million.

This is without doubt a remarkable figure: China’s 93 billionaire lawmakers have an accumulated wealth of US$504 billion while the 50 richest members of the U.S. Congress have a combined wealth of “only” US$2 billion!

The substantially higher number of millionaires among Chinese lawmakers, compared with the United States, results from the different, historically conditioned, physiognomy of China’s ruling capitalist class. American monopoly capitalists are a much “older,” longer-existing class. They have established a comparatively stable political and social division of labor. American billionaires don’t need to waste time in Congress in order to implement their dictates. They have, at their disposal, trusted politicians who act as loyal executives.

China’s monopoly bourgeoisie, by comparison, is a much younger class. It has existed only two or three decades. It is led by a much more centralized leadership. Without this structure, China could not have succeeded in catching up to the older, Western Great Powers. (China’s economy, as a whole, is still more backward than those of its rivals the United States, Europe, or Japan.) As a result, China’s ruling class has a less-established division of labor. Business and politics are more directly united at the personal level.

Another measure indicating China’s rise is what Chinese economists call “net social wealth.” This is the total of nonfinancial assets and net foreign assets. A recently published report by the China-based National Institution for Finance and Development calculates that China’s net social wealth reached 437 trillion yuan (US$63.66 trillion) at the end of 2016. This was equal to about 70 percent of the U.S. total and ahead of all other Great Powers.14

Capital Export and Military Spending

China and Russia (Russia to a lesser degree than China) are also increasingly becoming major foreign investors. This is confirmed by the latest figures for global capital export. While the United States remains the largest international investor, with 23.9 percent of the foreign direct investment (FDI) outflows in the year 2017, Japan is number two (11.2 percent), and China is number three (8.7 percent)—ahead of all European powers. Russia’s figure is lower, slightly less than half of Germany’s FDI.15

When we look at the accumulated stock of FDI outflows, one sees, again, the rapid progress made by China. Despite the fact that China only became an imperialist power about a decade ago, its FDI outward stock equaled the figures of other Great Powers (except the United States) by 2017.16

We can see a similar development with the investment in technology. Again, the United States remains the world’s leading country in terms of investment in research and development (US$463 billion for the year 2015). However, China is catching up rapidly. Beijing’s current five-year plan calls for increasing research-and-design spending to 2.5 percent of GDP, up from 2.1 percent in 2011-2015. As a result, it has now become the second-place country (US$377 billion). That is more than the entire European Union (US$346 billion) and two-and-a-half-times as much as Japan’s annual spending (US$155 billion).17

While Russia is weaker on an economic level, it still plays an important role given its military and political weight.18 In addition to important monopolies like Gazprom or Rosneft, Russia has a huge military-industrial complex making it the second largest military power behind the United States and ahead of all other imperialist states.

According to the latest study by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, the United States has a total inventory of 6,450 nuclear warheads. Russia has even more (6,850). France (300), China (280), and the UK (215) follow.19

A similar picture can be seen when looking at the list of the world’s ten top exporters of weapons. In the year 2016, the global market share of the United States was 33 percent, followed by Russia (23 percent), and China (6.2 percent).20

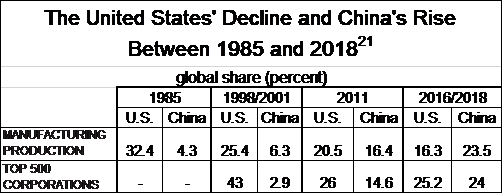

Furthermore, when analyzing the Great Powers it is crucial to take into account the dynamic of the development. The United States, the EU, and Japan are old, declining, imperialist powers while China and Russia are new, rising powers. To illustrate this dynamic, once again, we compare the economic development of the United States and China since 1985. When we compare the development of the United States’ versus China’s share of world manufacturing production, as well as proportions of the global top 500 corporations, we see the results laid out in the accompanying table.

At the Onset of a New Cold War

Given the historic crisis of capitalism and the massive shift in the power relations between the Great Powers, it is hardly surprising that the growth of tensions between the imperialist states is accelerating. The emergence of the extraordinarily chauvinistic (and bizarre) Trump administration is therefore not just a bad joke of history (the dominant appearance) but, equally, an expression of historical necessity. “Make America Great Again” objectively reflects the desperate efforts of U.S. imperialism to stop and reverse the advancing decline of its previous hegemonic position. The grotesque personage of Trump merely expresses the failure of the American bourgeoisie to achieve such a goal.

This massive intensification of Great Power rivalry is reflected in the growing global trade war, the cancellation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty by the U.S. administration, the tensions in the South China Sea, the U.S. aggression against Iran, as well as saber-rattling by leading politicians and military figures on all sides.

Let’s give a few examples from the recent past. Retired Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, former commander of the U.S. Army in Europe, warned at the Warsaw Security Forum in October 2018 that “in 15 years … it is a very strong likelihood that we will be at war with China.”22 Britain’s Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt warned while visiting Iran that a single, small event could spark a World War I-style catastrophe in the Middle East.23 A former U.S. Treasury Secretary, Henry Paulson, recently warned of the risks of an “Iron Curtain” descending between the world’s two largest economies.24 According to Chinese media, President Xi Jinping has told his military commanders to “concentrate preparations for fighting a war,” as tensions continue to grow over the future of the South China Sea and Taiwan.25 U.S. National Security Adviser John Bolton has stated that the United States is determined to push back China’s and Russia’s growing influence in Africa.26

Another expression of the increasing influence of an aggressive imperialist perspective is the rise of Peter Navarro in the Trump administration. He is the current White House adviser on trade. Navarro has authored several recent publications that identify China as the main rival of the United States. One of them has the clarion title The Coming China Wars. Unsurprisingly, Navarro is a strong advocate of high tariffs against the Middle Kingdom.27

Graham Allison, a former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense, advocates a similar foreign policy. Allison has introduced the phrase “the Thucydides Trap.” He argues that in most cases the confrontation between a rising power and a ruling power has resulted in bloodshed. Consequently, Allison has projected the likelihood of a major confrontation between the United States and China.28

Official Chinese media have similar sober expectations about the future relations between the Great Powers. Global Times, the international, English-language central organ of the ruling Communist Party of China, published an article that stated that even if China and the United States can avert a trade war in the short term, there is no reason for optimism:

In the short term, due to the win-win nature of trade, there is still room for negotiation in the trade disputes. Nevertheless, in the medium term, the United States has become aggressive toward the rise of China’s manufacturing sector and the narrowing of the gap in high-tech areas. In the long run, amid the concerns over the Thucydides’ Trap, an overall U.S. containment of China is not entirely impossible. In this sense, China will likely face more conflicts with the United States at different levels, and it is essential to be prepared for a protracted war.29

A whole sequence of books and studies have been published that focus on the increasing tensions between the Great Powers and warn of major confrontations in the foreseeable future. The Eurasia Group wrote, for example,

We aren’t on the brink of World War III. But absent a global security underwriter, and with a proliferation of subnational and non-state actors capable of destabilizing action, the world is a more dangerous place. The likelihood of geopolitical accidents has risen significantly, a trend that will continue. At some point, we’re likely to have a mistake that leads to a confrontation.30

In conclusion, we don’t believe that there will be a simple, orderly replacement of the United States-dominated world order by a China-dominated world order. True, the United States and the West, in general, are in decline and, yes, China is rising. However, it is absurd, a kind of bourgeois pacifism, to imagine that a global transfer of power, wealth, and influence would be possible without a world war. The decline of the West and the rise of the East mean, in the first place, an intensification of the contradictions between competing imperialist interests rigidly identified with, and defended through, nation-state structures. It means more trade wars, more proxy wars, and, eventually, major wars between rivals. The Western capitalist powers will not go down without a desperate struggle over the question of hegemony.

It would therefore be wrong to exclude the possibility that the Western powers could win such a confrontation. However, if the working class does not succeed in overthrowing all of the capitalist bandits in a timely manner, it is also possible that the result of such a world war will be the annihilation of humanity.

notes

- Michael Pröbsting, Anti-Imperialism in the Age of Great Power Rivalry. The Factors behind the Accelerating Rivalry between the U.S., China, Russia, EU and Japan. (RCIT Books, January 2019). This book can be read online or downloaded for free.

- Michael Pröbsting, “China’s Emergence as an Imperialist Power,” New Politics (No. 57, Summer 2014).

- Hong Kong Trade Development Council, Changing Global Production Landscape and Asia’s Flourishing Supply Chain, October 3, 2017, 1.

- Hong Kong Trade Development Council, 4.

- WTO: World Trade Statistical Review 2018, 23.

- “The World’s Largest Public Companies,” Forbes.

- Tomohiro Omura, “The Maturity of Emerging Economies and New Developments in the Global Economy,” Mitsui Global Strategic Studies Institute Monthly Report, April 2017, 4.

- UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2018 (New York and Geneva, 2018), 58.

- Hurun Report, “Global Rich List 2017”; see also Zhu Wenqian, “Beijing listed as billionaire capital of world once again,” China Daily, August 3, 2017; and Michael Pröbsting, “China’s ‘Socialist’ Billionaires,” RCIT, November 16, 2015.

- Luisa Kroll and Kerry A. Dolan, “Forbes 2017 Billionaires List: Meet the Richest People on the Planet,” Forbes, March 20, 2017; see also here.

- UBS and PwC, New visionaries and the Chinese Century. Billionaires insights 2018. A media release of the publishers that summarizes the results can be viewed here: “UBS/PwC Billionaires Report 2018: Total billionaire wealth grows 19 percent to a record USD 8.9 trillion,” October 26 2018.

- See also Michael Pröbsting, “China: A Paradise for Billionaires,” RCIT, October 27, 2018; and Michael Pröbsting, “The Global Super-Rich Get Even Richer,” RCIT, October 27, 2018.

- Yujing Liu, “China’s billionaire lawmakers are fewer and less wealthy, as 2018 stock market rout crimped their ranks and fortunes,” South China Morning Post, March 6, 2019.

- Xie Jun, “China’s social net wealth second highest, while imbalances need attention,” Global Times, December 27, 2018.

- UNCTAD: World Investment Report 2018, 184-187.

- UNCTAD: World Investment Report 2018, 188-191.

- U.S. Pentagon, “Assessing and Strengthening the Manufacturing and Defense Industrial Base and Supply Chain Resiliency of the United States, Report to President Donald J. Trump by the Interagency Task Force in Fulfillment of Executive Order 13806,” September 2018, 39; see also Visual Capitalist, “Chart: The Global Leaders in R&D Spending by Country and Company.”

- On our analysis of Russia as an imperialist power see e.g. Michael Pröbsting, “Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism and the Rise of Russia as a Great Power,” RCIT, August 2014; Michael Pröbsting, “Russia as a Great Imperialist Power,” RCIT, March 18, 2014.

- SIPRI Yearbook 2018, Armaments, Disarmament and International Security, 236.

- SIPRI Yearbook 2017 (Summary), 15.

- For the figures on manufacturing see UNIDO Industrial Development Report 2002/2003, 152 (for the years 1985 and 1998), UNIDO Industrial Development Report 2013, 196 resp. 202 (for the year 2011) and UNIDO Industrial Development Report 2018, 205 resp. 209 (for the year 2016). Note that manufacturing is not identical with industrial production since the latter also includes mining and the construction sector.

For the figures on the top 500 corporations see Wikipedia, “Fortune Global 500,” (for 2001), Agence France-Presse, “Chinese companies push out Japan on Fortune Global 500 list,” July 9, 2012 (for 2011), and “Fortune Global 500 List 2018: See Who Made It,” Fortune (for 2018).

- “Retired U.S. General Says War with China Likely in 15 Years,” The Associated Press, October 24, 2018.

- “UK foreign secretary warns of ‘First World War risk’ in Middle East,” Middle East Eye, November 20, 2018.

- Gordon Watts, “Hope springs eternal for a China-U.S. trade deal,” Asia Times, November 9, 2018.

- “Xi inspects PLA Southern Theater Command, stresses advancing commanding ability,” Xinhua, November 26, 2018; Jamie Seidel, “President Xi tells military to ‘concentrate preparation for fighting a war’,” news.com.au, October 29, 2018.

- See e.g. Steve Holland and Lesley Wroughton, “U.S. to counter China, Russia influence in Africa: Bolton,” Reuters, December 13, 2018; Michael Cohen, Samer Al-Atrush, Henry Meyer, and Margaret Talev, “America’s Moment of Truth in Africa: It’s Losing Out to China,” Bloomberg, December 14, 2018.

- See Peter Navarro, How China’s Economic Aggression Threatens the Technologies and Intellectual Property of the United States and the World, White House Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, June 2018; Peter Navarro, Crouching Tiger: What China’s Militarism Means for the World (Prometheus Books, 2015); Peter Navarro and Greg Autry, Death by China: Confronting the Dragon: A Global Call to Action for the Western World (Pearson Education, 2011); Peter Navarro, The Coming China Wars: Where They Will Be Fought and How They Can Be Won (Financial Times Press, 2006).

- See Graham Allison, “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?” The Atlantic, September 24, 2015; Graham T. Allison, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017); Graham Allison, “China and Russia: A Strategic Alliance in the Making,” The National Interest, December 14, 2018.

- Shen Jianguang, “China needs to prepare for long-term rivalry with the U.S. even if trade deal is reached,” Global Times, January 1, 2019.

- Eurasia Group: Top Risks 2018, 6.