Donald Rooum

English anarchism has produced a number of fine cartoonists, including Clifford Harper, John Olday, Paul Petard, and, arguably, the artist Hunt Emerson and the writer Alan Moore. Another is Donald Rooum, who is probably best known for his comic strip Wildcat and for the seven Wildcat collections that have been issued by the London-based Freedom Press.

English anarchism has produced a number of fine cartoonists, including Clifford Harper, John Olday, Paul Petard, and, arguably, the artist Hunt Emerson and the writer Alan Moore. Another is Donald Rooum, who is probably best known for his comic strip Wildcat and for the seven Wildcat collections that have been issued by the London-based Freedom Press.

Donald Rooum was born in Bradford in 1928, and he became an anarchist at the age of 16. As he told The Comics Journal in 2002, “for a period of about four weeks I belonged to the Young Communist League.” But “I didn’t like the earlier stages of the Communist program, which was to seize power and hold on to power for as long as it took for people to become so interdependent that the state would wither away. I didn’t understand why the state wouldn’t hold onto power indefinitely.”

“Progress toward anarchy,” he explained, “should start off in the direction of anarchy, not in precisely the opposite direction.” His father, who worked as a “machine metal worker in the bus depot,” was active in the Labour Party and soon became worried about his son’s political leanings. When his dad “went to a leading member of the local party,” the man said, “Encourage him, my friend. All the top people in the Labour Party were anarchists of one kind or another when they were younger.”

As it happened, Rooum remained committed to his youthful ideals. Conscripted into the military toward the end of World War II, he was given a political rating as a subversive, which meant that he couldn’t be posted overseas. As a result, he spent most of his service working in the kitchen of a “transit camp for married couples.” He did not receive a pension, but the army “did pay for my art school education,” and so he was able to study commercial design at the Regional College of Art, Bradford. In the early fifties he moved to London to find employment in the commercial arts, and to work with the circle around the newspaper Freedom. Long based in the East End of London, Freedom newspaper and the Freedom Press were originally launched in the 1880s by Peter Kropotkin, Charlotte Wilson, and a handful of other anti-statists. Rooum ended up working in advertising and then taught typographic design at the London College of Printing until he took early retirement. For many years he also pursued a freelance career as a gag cartoonist, and his cartoons turned up in the Daily Mirror, Peace News, Private Eye, the Spectator, and elsewhere. Wildcat started appearing in Freedom in 1974 and would continue to appear in its pages on a monthly or biweekly basis for the next four decades.

Rooum was briefly famous for his role in exposing corruption in the London police force. He had taken part in a 1963 demonstration in London against the King and Queen of Greece, who were in Britain for an official state visit only a few months after right-wing military officers had staged a coup in Greece with the tacit support of the monarchy. After the protest was over, a detective sergeant named Harold Challenor arrested Rooum along with four plainclothes police officers. At the time of the arrest, Challenor claimed to have recovered part of a brick from Rooum’s jacket, which meant that Rooum could be charged with carrying an offensive weapon. Fortunately, as he was waiting in a holding cell, he remembered reading that “if a stone had been in my pocket it would have left traces. … I knew I had a case, if I could show that the suit I was wearing had not been tampered with after the demonstration.” The police made “two big mistakes,” Rooum later explained. “The first was that they kept me overnight in the holding cell so that there was no doubt about the suit I was wearing. The other was that the police never put the brick in my pocket. This not only led to my acquittal, but to a public inquiry, which received an enormous amount of press coverage at the time. A string of convictions from other demonstrations were overturned as a result of this case.”

Toward the end of an interview with Rooum for Comics Journal I asked him whether “anarchists have any reason to be optimistic these days.” He responded,

Well, I have. Any anarchist of my age must think there has been some progress over the past 60 years. Certain activities that were once considered crimes are no longer prosecuted. Take homosexuality, for example. We now have a homosexual police commander. Fifty years ago he would have been arrested. Also, the general attitude toward the monarchy has changed. When [the satirical magazine] Private Eye first started they were very polite toward the Queen. Now, any cartoonist can be as rude as they like about the royal family. The whole culture of deference toward authority has gone down. So that’s good news.

My final question was a follow-up: “And would you mention the fall of the Soviet system?” “I don’t know,” he said, after a long pause. “There were two great powers for 50 years, and now there is only one. I’m not sure we’re any safer.”

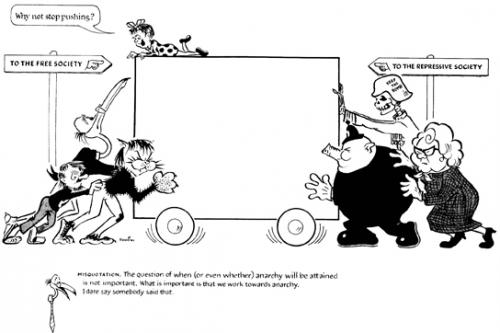

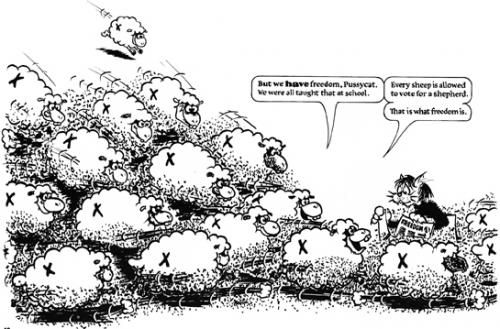

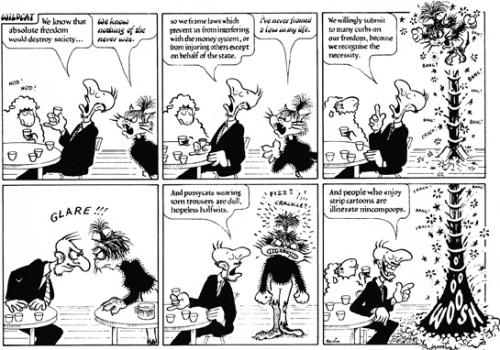

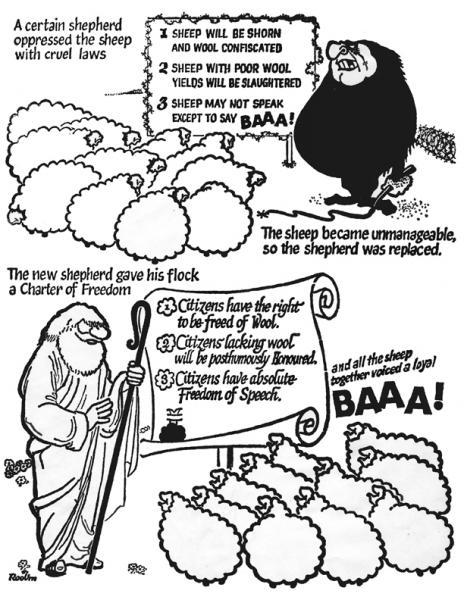

These selections of Rooum’s work are mostly self-explanatory—the first image, for example, expresses his conception of social progress as a question of pushing the cart forward rather than, say, going to war. On the left hand side you have the left-Labour activist in sandals, the egghead stork, and Wildcat herself, who wears ragged trousers; while on the right, pushing in the opposite direction, you have a policeman, a skeleton, and Mary Whitehouse, the midcentury anti-porn campaigner. In the second image Wildcat tries to sell Freedom to sheep who somehow manage to tell themselves that voting matters. The thick motion lines buried beneath the sheep’s hooves is a classic Rooum touch that gives the image a heightened sense of charge and energy. For some reason there’s a mermaid in the third image, in the lower left of the panel, who looks a lot like Wildcat. There’s also a strong sense of class division that is characteristic of a great deal of English cartooning, not just anarchist or, indeed, self-consciously left-wing.

While the first three images are single panel, and could be reasonably described as editorial cartoons, the fourth and fifth images are squarely in the comic strip tradition. The fourth shows Wildcat and the egg-headed stork conversing about issues of the day. No to this! And no to that! Wildcat exclaims, in elegantly drawn bursts of dialogue. “How about negativism?” asks the stork. “Thanks,” says Wildcat, “No to negativism!” The stork can only shake Wildcat out of her rut by offering her a nice cup of tea. Yes!

The final image is by far the most complex, at least in formal terms. Wildcat’s vertical outburst on the far right of the strip not only provides a striking visual contrast to the misshapen pontificator’s lumpy curves, but also defies the laws of space and time. “Part of the cartoonist’s job,” Rooum told the Comics Journal, “is to decorate the page. It’s got to add to the visual impact of the page.” In the same interview, Rooum described Wildcat as “an angry anarchist, without much of an intellectual basis for her actions. She knows what she wants.” I then suggested there’s a sense in which, “no matter how patiently the stork explains things to her she will always be on a tear.” “Ah yes,” replied Rooum, “she’s a comic strip character.”