I

During the tumultuous years that followed the horrors of World War I, especially in the period of 1917 to the early 1920s, the Russian working class became an inspiration to workers around the world.

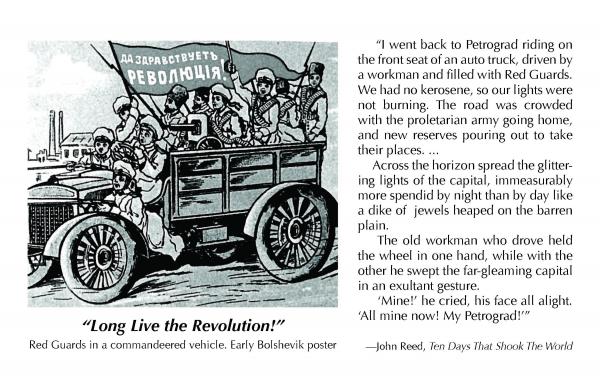

The Russian Revolution of October 1917 did several things that represented a watershed for the socialist movement. First, of course, for the first time in world history working people—the proletariat and the peasantry—overthrew the old order of monarchical, aristocratic, and capitalist government in Russia, took power themselves, and founded a new revolutionary regime aimed at establishing socialism. With the exception of the tragically short-lived Paris Commune of 1871, lasting just seventy days, a successful workers’ revolution had never happened before, and never in an entire nation.

Second, the revolution established an entirely new model of government based on the soviets, or councils of workers, soldiers, sailors, and peasants that had grown out of strikes, land seizures, desertions, and mutinies. Thrown up in struggle to coordinate militant action, the soviets became a kind of government, an alternative to the parliament during a brief period of dual power, and then—after the Bolsheviks dispersed the parliament—the soviets became the government. The common people now held power. All of the left parties believed in principle in a multiparty workers’ democracy, and in the first year the Soviet government had a multiparty leadership, made up of the Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, Social Revolutionaries, the Maximalists, and even anarchists, all of them arguing within the soviets for their various programs and strategies.

Third, the revolution was led by a new sort of political party, the Bolsheviks, a party that strove to combine internal democracy with centralization and discipline. The Bolshevik Party played a key role at every stage of the revolution, above all in the defense of Petrograd, in the calls for “Land, Peace, and Bread” and “All Power to the Soviets,” and, not least, in the organization of the insurrection that overthrew the February Revolution’s capitalist government and thrust power into the hands of the soviets. The Bolshevik Party, later called the Communist Party, was, during the 1917-1921 period, a quite democratic organization with open discussion and debate, tendencies and factions.1 The two outstanding leaders of the party in this period, Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, were each sometimes in a minority, even a minority of one, and at other times they were divided against each other, as the Bolsheviks wrestled with the issues of withdrawing Soviet Russia from World War I, foreign intervention, the counter-revolutionary White Armies, and the civil war, as well as with many other life-and-death issues.

Fourth and finally, within a year the Russian Revolutionaries—who had witnessed the betrayal of socialist ideals by the leaders of the Second (Socialist) International and then that organization’s collapse at the outbreak of World War I, created a new Communist International to coordinate revolutionary socialist struggle around the world. The Communist Party of Soviet Russia became deeply involved in negotiations with the Socialist parties in Europe as well as in discussions with anarchists and syndicalists. The Communist International became particularly involved in developments in Germany, which was seen at the time as the only possible salvation of the revolution in Russia since no one imagined that socialism could be created in an economically backward nation such as Russia. As Lenin said more than once, “Without Germany we are lost.”

These four developments—the event of the Russian Revolution itself, the workers’ soviets as the government, the Bolshevik Party leadership, and the Communist International as a party of world revolution—represented a dramatic break with the socialist movement of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and raised the possibility of a spreading revolutionary movement that might transform the entire world. From 1918 to the 1920s, hundreds of thousands of European workers, and many in other parts of the world, wanted to become Bolsheviks, and millions wanted to create soviets, though as Victor Serge wrote of that period, almost no one outside of Russia had any idea what either “Bolshevik” or “soviet” meant. Still, though they only vaguely understood what had happened there, for millions of working people around the globe, to say “Russia” was to say revolution, socialism, and freedom.

II

Yet within a decade the revolution had been overthrown by a bureaucratic counter-revolution, a process far more violent than the October revolution itself. And within two decades a section of the former revolutionaries led by Joseph Stalin had, through this counter-revolutionary process, created an altogether new society, dominated by a new bureaucratic ruling class—a ruling class as oppressive and exploitive as any that had come before—a class not only taking power in Russia, but also with ambitions of empire abroad.

Like the Russian Revolution of October 1917, the counter-revolution that began in the mid-1920s and definitively ended in the late 1930s also provided an alternative to the earlier socialist movement’s models and theories, as well as to those of the early soviet period. First, Joseph Stalin and his collaborators established the model of one-party rule as a principle, something initially undreamed of by the Russian revolutionaries of 1917. While one-party rule had emerged earlier, it was Stalin who made it an ideal, arguing that Communist Party rule was by definition working-class rule. This was moreover a top-down, vertical party, without factions, without debate, where commands came down from on high to functionaries below and then to the workers in their factories and peasants on their farms. The soviets, which had ceased to function during the “War Communism” period, were by the mid-1920s effectively run by the Communist Party.

Second, the party fused with the state to take command of the means of production that had been nationalized earlier, while at the same time bureaucratic control and planning came to substitute for the idea of democratic socialization and planning of industry and agriculture. This bureaucratic collectivism was a novel and, at the time, a unique regime. With the one-party state in control of politics, the economy, and society, the Soviet Union became totalitarian, controlling every organization and forbidding any activities that it did not control. Communist planning, a forced march to modernization, proved to be a horror. The state’s forced collectivization of agriculture from 1928 to 1940 would take the lives of as many as six million peasants in Ukraine and Russia, while the First Five-Year Plan of 1928-1932 and the plans that followed would recapitulate the savage exploitation of the working class that had taken place earlier in Western Europe during the industrial revolution.

Third, under Stalin, the idea of revolutionary internationalism and the belief that other European revolutions were necessary to save the Russian Revolution were replaced by the notion of “socialism in one country.” During Soviet Russia’s first years, Lenin once said that the Bolsheviks would have gladly sacrificed the Russian Revolution to achieve a German revolution. Further, because of its high level of economic development, a German workers’ state would give Russia’s workers’ state a far better chance of survival. For Stalin it was just the reverse: Other revolutions in China, Germany, and Spain were sacrificed in the interest of preserving the Soviet Union. Consequently, the Communist International, dominated by the Russian Communist Party, ceased to be a center of the revolutionary workers’ movement and became instead an agent of the Soviet Union’s foreign policy. The test of all politics ceased to be what was good for the international movement and became instead what was good for the rulers of the Soviet Union.

III

Despite this dramatic turn in the revolution between the mid-1920s and the 1930s, the Soviet Union and the Communist International continued to exert an enormous influence on the working class worldwide that had been so inspired by October 1917. The Russian Communist Party had the authority to influence revolutionary movements around the globe. Stalin’s first major test of foreign policy, the revolutionary situation in China from 1925 to 1927, proved to be a disaster after he insisted that the Chinese Communists remain within the Kuo-Min-Tang, the bourgeois nationalist party of Chiang Kai-shek, rather than forming their own party. Chiang and the KMT used the Communists until they became a threat and then turned on them and virtually annihilated the Communists in Shanghai in 1927.

Only the most knowledgeable socialists had followed Chinese developments, and because of the reputation of October 1917, the Communist International still commanded the allegiance of millions of workers in Europe. In the period 1928-1935, Stalin, as the effective leader of the Communist International, put forward the new theory of “social fascism”—that is, the Social Democrats were in essence the same as the fascists, a position that prevented joint action by German Communists and Social Democrats, thus contributing to the rise and ultimate victory of the Nazis. These developments in both China and Germany represented a sharp break with the early Communist International’s advocacy of the “united front”—the joint action of working-class parties against the far right combined with open criticism of class-collaborationist Social Democratic policies. Once Adolf Hitler came to power, Social Democrats and Communists went together to concentration camps and to the grave.

After the shock of Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933, in mid-1935 Stalin’s Communist International changed course and adopted the “popular front,” meaning unity not only with Social Democrats but also with capitalist parties, even conservative ones. This too was a break with early Communist International policy that had called for the complete independence of working-class parties. This new policy was largely responsible for the defeat of a revolutionary movement in Spain during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939. The Communist International and the Spanish Communist Party (PCE) worked to defend the Republic—in fact the Communists who were providing military assistance practically came to control the Spanish government—while at the same time Communists worked against revolutionary anarchists and socialists in the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM). Stalin’s secret police, the KGB, worked with the PCE and the Communist International brigades to assassinate anarchists and POUM leaders such as Andrés Nin. With the revolutionary movement crushed, General Francisco Franco and his fascist Falange won the civil war and proceeded to annihilate the Communists and what was left of the anarchist and revolutionary socialist left.

Stalin negotiated with England and France, knowing full well that they had no desire to make an alliance with Communist Russia. Stalin did so only as a strategy to pressure Hitler into making a deal with the Soviet Union, a deal that would give Stalin more territory and a buffer on the west. The Hitler-Stalin Pact of August 1939 was followed by the division of Poland, with Germany invading from the west and the Soviet Union from the east. Later in 1939 the Soviet Union also invaded Finland, taking 11 percent of its territory. The bureaucratic rulers of the Soviet Union, born into an imperialist world, having become Russian nationalists, and driven by their own ambitions, now also became imperialists themselves.

The Soviet alliance with Nazi Germany represented only a brief interlude. In June of 1941, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. Stalin then brought the Soviet Union to join the Allied powers—the United States, Great Britain, Free France, and nationalist China—in the war against the Axis: Germany, Italy, and Japan. Once again, now allied with the world’s greatest imperial powers, the Communist International called upon its member parties to support democracy and restrain revolutionary labor movements or colonial rebellions that might jeopardize its alliance with the empires.

Despite those developments, official Communism, still living on the legacy of 1917, continued to hold authority among millions. Some argued that the Soviet Union’s remarkable, if incredibly costly, victory—at least 25 million lives lost—in the struggle to defend itself against Nazi Germany in World War II proved the superiority of the Russian Communists’ “socialist” organization and ideology. Then too there was the Soviet Union’s liberation of Eastern Europe from the Nazis, a liberation, however, that quickly led to Soviet domination and the imposition of Communist governments from the Baltic to Bulgaria and from Ukraine to East Germany.2

Whatever else it might be, Stalinist Communism appeared to be a winner, spreading across the globe from Germany to China by 1949. The United States ended World War II by dropping atomic bombs on the civilian populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in August of 1945, but the Soviet Union succeeded in producing its own atom bomb in 1949. Then the Soviets launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, suggesting that Communist Russia might also be the world’s greatest industrial, scientific, and potentially military power. All of this, Communists argued, was because of the Russian Revolution of 1917 that continued to live on in the Soviet Union’s “socialist” society.

Those living in the Communist world knew better. In the Soviet Union and throughout Eastern Europe a distinct political, economic, and social system emerged, one that privileged the Communist elite, generated inequality, and suppressed dissent. Repressive at its core, it was necessarily a system of fear and lies. In the mature bureaucratic collectivist system, the Communist Party, through its control of the state, also controlled the means of production, and so Communist bureaucrats elaborated the country’s economic plans.

Yet planning in a totalitarian society generated tremendous economic contradictions. The directors of industrial sectors and the managers of factories and farms were afraid of producing honest reports for fear of losing their jobs or even their lives. Their false reports to their superiors inevitably distorted all attempts at rational planning. To compensate for the discrepancy between the plan and actual potential, and to meet the bureaucracy’s latest Five-Year Plan demands, the directors stockpiled surpluses of raw materials and machines so as to be prepared to fulfill unrealistic quotas. At the same time these Communist captains of industry and factory bosses competed with each over for these materials through struggles in the bureaucracy and in the black market, just as they competed to hire away from each other the most skilled managers, technicians, and workers. Remarkably, by prodigious, wasteful, and environmentally disastrous industrial production, the Soviet economic planners and directors managed to raise the standard of living of the working class and peasantry, though consumer goods remained far inferior to those in capitalist Europe and the United States.

The undeniable legacy of the revolution that remained in the totalitarian society was a safety net of guaranteed jobs, virtually free housing, simple clothing, basic food, free health care, and a meritocratic education system. Productivity and income remained low. As the joke went, “We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.” Through the mass production of shoddy goods, through rationing, and long waits in queues, basic human needs were met, if unequally, in a society without democracy or freedom of expression.

While the Soviet system shared with capitalism the evils of class rule and privilege, oppression and exploitation, economic problems and environmental catastrophes, it operated through altogether different mechanisms. With enormous territory, vast natural resources, one of the world’s largest populations, and a cohesive ruling class bent on keeping and expanding its power, the Soviet Union became—as already demonstrated in World War II in Finland, the Baltic, and Poland, and confirmed following the war in Eastern Europe—one of the world’s great imperialist powers. For a generation, during the Cold War years of 1945 to 1960, the United States dominated the capitalist world, the Soviet Union dominated the Communist world, and both fought to influence and if possible to draw into their respective spheres the nations of the Third World.

The question of Communism had already become somewhat more complicated by 1948-1949 when Josip Broz Tito’s Communist Yugoslavia broke with Stalin, followed by the Sino-Soviet split of the early 1960s. Bureaucratic collectivism became definitively divided into hostile camps, with China eventually joining in alliance with the United States.

Still, outside of the Soviet Union, many remained believers in the Communist system of the Soviet Union, a system that Russians themselves now cynically endured. Even as the purges and then murders of tens of thousands of revolutionary socialists and the deaths of millions of peasants during the forced collectivization of Soviet agriculture became common knowledge (for some as early as the 1930s and for many certainly by the 1950s), some—dogmatic, deceived, or in denial—continued to proclaim the Soviet Union was a workers’ state. Others, especially in the 1950s in the Third World—what today we would call the developing nations—saw in the Soviet Union a model for rapid modernization. Yet others, engaged in revolutionary nationalist or socialist movements, whatever they thought of the Soviet Union, turned to the Russian Communists for diplomatic, economic, and military support.

Nikita Khrushchev’s secret speech to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in February 1956 revealed Joseph Stalin’s crimes. That speech was followed in October and November by the Hungarian Revolution against Soviet power—a workers’ revolution against the Communist state and the Soviet Union. Finally, many who had previously supported the Soviet Union began to break from Communism. When the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia and suppressed the Prague Spring in 1968, there was another mass exodus from Communist parties around the world.

IV

What took them so long? From the early 1920s through the 1950s many had already asked what had gone wrong. Others continued to ask that question until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. The answers, of course, varied. Some argued that one or another specific moment or development in the process—Lenin’s call for a party of “professional revolutionaries” in 1903, the dispersal of the Duma in 1917, the establishment of one-party rule, the suppression of the Kronstadt Rebellion of 1921, Stalin’s victory in the struggle to succeed Lenin between 1924 and 1927, or Stalin’s consolidation of power between 1927 and 1937—had led to the failure of a revolutionary workers’ movement that might otherwise have been successful. These debates preoccupied revolutionary socialists for decades and still do.

The most popular argument, however, was the belief that Soviet Communism was proof that, given human nature, socialism was an impossibility. This view of humankind’s inherent and utter inability to establish a democratic, egalitarian, and libertarian social order that could provide a good life for all became the stuff of textbooks, newspaper editorials, and TV and radio discussions around the world. Pundits, professors, and politicians argued that revolution always leads to terror, then “Thermidor,” and finally dictatorship. It was human nature. Capitalism alone worked; nothing else was possible.

Human nature arguments, so much easier than having to wrestle with historical specificity, seduced with their simplicity. The counter-revolution that swept away the Russian Revolution and its all-too-brief experience of workers’ democracy was a terrible tragedy. But the even greater tragedy was that consequently virtually all of the revolutionary European proletariat of the generations of 1900-1945 perished in Hitler’s and Stalin’s purges and death camps, or in World War II and the Holocaust. Consequently, by the 1950s the significance of the original workers’ revolution of 1917—a revolution from below—was largely erased from the collective memory of the working class in both Eastern and Western Europe and throughout the world.

V

How do we who today consider ourselves to be revolutionary socialists in the “socialism from below” tradition explain what happened to the great socialist experiment? The most common explanation usually given by those in the Trotskyist tradition—and there is much truth in it—is that objective conditions brought about the transformation of soviet democracy into Stalinist totalitarianism: the backwardness of Russia, the violence and destruction of the civil war, the invasion by 16 foreign nations (including the United States, by the way), and the famine of 1921-1922 that took as many as five million lives.

Then too, those objective conditions included the social imbalance: the small number of workers and the enormous number of peasants whose desire for land overrode for them all other considerations. The Bolshevik Party’s worker-members went off by the thousands to fight and in many cases to die in the new Red Army, while others were dispersed over Russia’s enormous territory to become civilian administrators of far-flung provinces and cities or of mines and factories. At the same time that the new Communist soviet government was fighting the White Armies in the civil war, other left groups rebelled against the Bolsheviks: Mensheviks, Social Revolutionaries, and anarchists all took up arms. Throughout all of this upheaval, production declined and the working class shrank as workers left the cities to go back to the villages where there might be food. The wonder is that in such conditions the workers’ revolution in some fashion survived into the 1920s.

Still, the objective situation, as important as it is, does not adequately explain what happened, because even within the limitations of those objective conditions there remained latitude for different choices by the Bolshevik Party leaders, by other parties, by the soviets, and by “ordinary” workers and peasants themselves. Turning around the clauses in Marx’s famous quote from the Eighteenth Brumaire, on the basis of the historical conditions in which they find themselves, men and women still make their own decisions. Some on the far left argue that every decision made by Lenin and the Bolshevik leadership was correct, at least until Lenin’s death in 1924, but in fact they were not flawless, and some decisions they made, whatever their intentions, contributed to the development of Stalinism—which is not to say that Bolshevism was destined to lead to Stalinism.

The absolutely necessary policy of War Communism—subordinating everything to winning the war against the White Armies through requisitioning, rationing, and widespread nationalization of property—replaced soviet democracy with a Bolshevik-led militarization of the entire society. After the foreign invasion of Russia, in order to win the civil war, “red terror” became essential to defend the revolution. The problem was that both the machinery and the mentality of the terror lived on after the civil war was won. The Bolshevik Party took command of the soviets, eliminating the other parties—one of a series of decisions and practices that contributed to bringing about the end of multiparty democracy and of the internal democracy of the Bolshevik Party itself beginning in 1918.

The February Revolution of 1917 had abolished the death penalty, and the October Revolution had confirmed that policy, but in less than a year the death penalty was revived. The re-establishment of the death penalty in 1918, with the execution of Fanny Kaplan after her attempt on the life of Lenin, was one of the early serious errors. The state could now kill the criminally accused, though Communist Party members would not be killed until 1934. The unlimited power of the Cheka, the secret police, from the time of its establishment in December 1917, was another serious error. The Cheka, created by an order of Lenin, had the power to arrest, to try in secret and without defense, to pass judgment, and to execute people as it saw fit. As Victor Serge writes, a “revolutionary tribunal functioning in the light of day” would have attained “the same efficiency with far less abuse and depravity.”3

At the same time, with the economy in decline and industry decaying, the working class shrinking, and its most dedicated activists going off to either fight the war or administer government, the soviets ceased to have their earlier lively character and became “no more than an auxiliary organ of the Party.” Mere shells, the soviets had by 1919 ceased to take initiative or to manage anything. The Bolshevik Party itself was transformed as careerists flooded the party and corrupt elements came over to the winning side. “Within the Party the remedy to this evil had to be, in fact was, the discreet dictatorship of the old, honest, and incorruptible members, in other words the Old Guard,” writes Serge.4

By 1919 Lenin, making a virtue of necessity, was arguing that the dictatorship of the party was the dictatorship of the working class. The Bolshevik Party went on to ban factions in 1921, as within the party appointment from above replaced election from below, and debate and discussion began to be suppressed. These developments contributed to the dangerous tendency toward displacement from the soviets to the party and within the party from the bottom toward the top.

The continuing civil war and the privations experienced by the population understandably led to rebellions against the Soviet state. The most important rebellion of peasants protesting requisitioning took place in Tambov in 1920-1921, but there were a number of others as well. The sailors at the Kronstadt naval base revolted in March 1921, calling for new elections to the soviets, freedom of the press and free speech, and the right of peasants to make use of their own land. Their rebellion was at its roots a rebellion against the regime of War Communism, both its economic privations and lack of democracy.

While the Kronstadt sailors took a few Communists prisoner, they harmed no one and the rebellion did not immediately pose a threat to the Soviet government. Yet the Bolsheviks lied to the workers, telling them the Kronstadt was in the hands of the White Armies. Lenin sent the Bolshevik Mikhail Kalinin to deal with the rebellion. When negotiations failed to resolve the situation, the Bolsheviks attacked Kronstadt, leading to thousands of deaths with as many as 10,000 Red Army soldiers and an unknown number of rebels killed in the battle, as well as an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 rebels executed afterwards.

The unnecessarily violent suppression of this revolt represented one of the great mistakes of the Soviet government’s early years.5 Interestingly, Serge, who deeply sympathized with the Kronstadt rebels, decided nonetheless to continue to support the Bolsheviks. He wrote, “If the Bolshevik dictatorship fell, it was only a short step to chaos, and through chaos to a peasant rising, the massacre of the Communists, the return of the émigrés, and in the end, through the sheer force of events, another dictatorship, this time anti-proletarian.”6

Lenin convinced the Bolshevik Party of the necessity of a New Economic Policy (NEP). While the state continued to control finance and the great industries, small-scale capitalist production and commerce were permitted in the city and the countryside. Nikolai Bukharin became a principal advocate after Lenin’s death of continuing to expand the NEP program. While the economy revived, some Bolsheviks now worried about the NEP men (capitalists), the kulaks (wealthy peasants), and overwhelming bureaucracy. The fear of the restoration of capitalism in Russia led Trotsky and others to see the principal danger on the pro-capitalist right, while minimizing the threat of the coalescing of the caste of bureaucrats gradually taking command of the Soviet state.

While there are other Bolshevik errors we might consider, those we have discussed demonstrate the way in which objective circumstances in combination with misguided political decisions gradually established the basis for a transition from workers’ democracy to bureaucratic collectivism. Already by 1919 there was little democracy in the soviets or in the Communist Party, and by March 1921 there was virtually none. By the early 1920s the workers’ state had become, said Lenin, “a workers’ state with bureaucratic deformations.”

With Lenin’s death, a succession struggle broke out among various shifting factions and individual leaders of the Communist Party, most prominent among them Kamenev, Zinoviev, Bukharin, Trotsky, and Stalin. While Stalin moved toward the consolidation of his control over the party and the state, ironically no one understood at the time what was happening. The Bolsheviks had always feared a capitalist revolution that would re-establish private property, but Stalin went beyond defending to expanding state property. Consequently, his opponents on the left utterly miscalculated, often supporting Stalin against what they saw as the more dangerous positions of Bukharin on the right. By 1927, Stalin had taken control of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and of the Communist International. Within a few years, working class strikes, protests from the soviets, and opposition within the Communist Party had been crushed. Stalin’s secret police rounded up, imprisoned, and eventually killed most of the Old Bolsheviks and hundreds of thousands of others. By 1940 Stalin’s counter-revolution was complete.

Leon Trotsky, the most famous socialist opponent of Stalin, had refused to join with the Workers’ Opposition or other Bolshevik oppositions that arose between 1919 and 1921. He declined to take his criticism of Stalin outside of the party to the Russian working people, believing that outside of the Bolsheviks there was no hope. By 1923, however, Trotsky established the Left Opposition, a faction within the Bolsheviks, and in 1924 he published The New Course, arguing that it was necessary to reform the party by democratizing it. His was perhaps a reasonable point of view in 1924, when there was hope that democracy might be revived in the party, though it is not clear that in itself this would have led then to the re-establishment of soviet power, that is, the power of workers over Soviet society. And certainly by 1927, when democracy was dead in the soviets, the trade unions, and the party, Trotsky’s view no longer made any sense at all.

The working class had changed as a new generation of peasants had come into the cities to take industrial jobs. The Communist Party had also changed. After Lenin’s death in 1924, the “Lenin levy” brought 240,000 workers with little or no political experience into the Communist Party, increasing its membership by 50 percent. As Trotsky, Gregory Zinoviev, and Lev Kamenev discovered when their United or Joint Opposition attempted in 1928 to take their reform program into the factories and to the new working class and new Communists, this was not the revolutionary working class of just a decade before. The Communists and other workers shouted them down.

Workers’ democracy had ended earlier, but unquestionably by the late 1920s workers no longer had any influence over the government and by extension no control over the economy. Socialism in such circumstances did not and could not exist. Yet Trotsky, then in exile, continued, despite the suppression of workers’ democracy, to call for the “defense of the Soviet Union,” arguing mistakenly that workers’ consciousness of the earlier experience of the October Revolution and the nationalization of the means of production meant that Russia could be still reformed or needed only a political, not a social, revolution. Trotsky lost sight of the intrinsic necessity of the practice of democracy to the existence of a workers’ state.

Trotsky found few supporters and virtually no allies in Europe, dominated as the working class was by Social Democracy and the Communist International. He rejected the idea of a broad, non-Communist left alliance in defense of socialist democracy, opting instead to try to build a revolutionary international. His Fourth International, a new alliance of Marxist organizations with no mass parties among them, was stillborn. His fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the Communist bureaucracy led him, in the late 1920s and 1930s, to a series of deeply contradictory positions on the nature of the Soviet Union. He continued to argue that the Soviet Union, because its property remained nationalized, had to be defended as a “workers’ state,” albeit “degenerated.” Various Trotskyists broke with him on this issue, arguing as we have here that bureaucratic Communism represented a new form of class society and imperialism as well.7 And on the eve of World War II he made erroneous predictions: workers’ revolutions in Europe and the fall of the Soviet bureaucracy by the war’s end.

After Trotsky’s assassination in August 1940 and then the end of the war, the Fourth International added to his mistaken analysis of the Soviet Union even more erroneous and pernicious notions, particularly the idea that the Eastern European countries conquered by the Soviet Union were somehow “proletarian” though born “bureaucratically deformed.” Workers’ revolutions, according to Trotsky’s orthodox followers, apparently were no longer necessary to bring about workers’ states.

The Russian Revolution’s democratic period continues to inspire us, even though it is clear that the disastrous conditions of the civil war, War Communism, and the excesses of the terror worked to extinguish democracy and led to a series of decisions that set the revolution on a course toward bureaucratic counter-revolution. The principal lesson we take from these experiences of revolution and counter-revolution is the centrality of democracy to the establishment, defense, and construction of socialism.

Afterword

The analysis developed in this article comes from the tradition of a number of people who mostly were part of the Trotskyist movement, most important among them Max Shachtman. Though he later moved to the right, that in no way vitiates the analysis he made when he was still a revolutionary. This was, broadly speaking, the view of the founders of New Politics, who came out of that tradition. Other political activists and intellectuals in a number of countries have, over the years, come to similar views of the nature of bureaucratic Communism and of the centrality of democracy to the revolutionary process and to the construction of a new society.

Footnotes

1. See, on the Bolshevik Party’s internal life: Marcel Liebman, Leninism Under Lenin (London: Merlin Press, 1975) and Alexander Rabinowitch, The Bolsheviks Come to Power: The Revolution of 1917 in Petrograd (W. W. Norton, 1978).

2. Under Communist Party leadership, Albania and Yugoslavia carried out genuine national revolutions, creating bureaucratic Communist states. Czechoslovakia’s complicated “revolution” involved an alliance between the Social Democrats and the Communists, workers’ strikes, and the nearby presence of the Red Army.

3. Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary, trans. by Peter Sedgwick (Writers and Readers, 1984), 81.

4. Serge, Memoirs, 119.

5. Victor Serge and Leon Trotsky, La lute contre le stalinisme: textes 1936-1939, présentés par Michel Dreyfus (Paris: Maspero, 1977), Serge, “Kronstadt,” 177-181.

6. Serge, Memoirs, 128-29.

7. Among them: Max Shachtman, The Bureaucratic Revolution: The Rise of the Stalinist State (The Donald Press, 1962); Ante Ciliga, The Russian Enigma (London: Ink Links, 1979); Ernest Haberkern and Arthur Lipow, eds., Neither Capitalism nor Socialism: Theories of Bureaucratic Collectivism (Atlantic Highlands: Humanities Press, 1996).

Questions of Soviet History

Old anarchists I have known typically referred to Leon Trotsky as the “butcher of Kronstadt”, noting that it was he who commanded the Red Army as it marched on Kronstadt.

I have to say that I was puzzled by the comments on Soviet diplomacy in the pre-WWII period, which suggests that Stalin always preferred an alliance with Hitler, and had no serious interest in building an alliance with western democracies. This conflicts with every narrative I have encountered and I wonder where is the documentation for such a contrary view?

Democracy, Workers and Peasants

“The principal lesson we take from these experiences of revolution and counter-revolution is the centrality of democracy to the establishment, defense, and construction of socialism,” writes Dan. But how could democracy — majority rule — be relevant to socialist construction in Russia where the majority of the population — 80% — was made up of peasants who had no interest in building socialism? Could democracy really make up for the missing material basis — a majority working class? Certainly, all pre-1921 Marxists — Trotsky Lenin, Luxemburg, Kautsky — based their case *against* socialism in Russia on the elementary proposition that only workers — not peasants — were agents of socialism. Analysis of the Russian experience must begin — but certainly not end — with the political economy of small peasant landholding because it erects insuperable barriers to the democratic development of the forces of production, to building socialism. That, I think, is the principle lesson of the post-1917 Russian experience, a lesson which is inapplicable — because irrelevant — to socialists in the US and other developed capitalist countries. This is because proletarians are in the majority, and no conflict could possibly arise between workers’ rule and majority rule, between democracy and socialism.