Capturing “the Spirit of Struggle”

Rosa Luxemburg has been the subject of numerous works of literary fiction in the century since her death, including Karl and Rosa, the final book of Alfred Döblin’s multivolume November 1918: A German Revolution (1950); Rosa, the first in Jonathan Rabb’s Berlin trilogy (2005); and Kate Evans’ graphic novel Red Rosa (2015). She also makes occasional appearances in a broad and diverse range of global literature. The 1931 Japanese proletarian novel Yasuko by Takiji Kobayashi, for example, contains this exchange between two factory workers:

Rosa Luxemburg has been the subject of numerous works of literary fiction in the century since her death, including Karl and Rosa, the final book of Alfred Döblin’s multivolume November 1918: A German Revolution (1950); Rosa, the first in Jonathan Rabb’s Berlin trilogy (2005); and Kate Evans’ graphic novel Red Rosa (2015). She also makes occasional appearances in a broad and diverse range of global literature. The 1931 Japanese proletarian novel Yasuko by Takiji Kobayashi, for example, contains this exchange between two factory workers:

But Yasuko, her cheeks flushed, spoke passionately of the things she had been thinking about. In the end she said, “I can’t remember her name, but there’s a woman who devoted her life to workers and peasants and who’s famous throughout the world. Here’s what she says.” Yasuko closed her eyes for a moment to recall the phrase. Her lowered long lashes were beautiful. “She says, ‘We must not live like trampled frogs’!”

Okei unwittingly raised her eyebrows.

“Ah, I remember now!” exclaimed Yasuko. “She’s the great woman revolutionary, Rosa Luxemburg.” (150)

Shortly after, Yasuko reflects further:

Looking at it from a different perspective, this work was extremely difficult and required a great many sacrifices, as the union man had said countless times and as was written in the books she had borrowed. Rosa Luxemburg, the woman who had spoken about trampled frogs, had been thrown into prison dozens of times for her work and was finally beaten to death with rifle butts. It was a noble sacrifice for the sake of the exploited and hungry working people of the whole world. Her life was unforgettable, especially for the women of the working class.

The letters that Rosa Luxemburg had sent from prison to her comrades on the outside were collected and published as a book in Japan too. The union man had brought her a copy and urged her to read it. Each evening after her work ended, Yasuko climbed up to her attic room to read it, and she had finished it within three days. It astounded her most of all that Rosa was a woman, just as she was. (151–52)

In keeping with Luxemburg’s habitual consultation of narrative fiction for historical insights, we can learn a great deal about her from these literary representations. Yasuko’s account, albeit romanticized, touches on the keynotes of Luxemburg’s global legacy.

Born and raised in Russian-occupied Poland, Luxemburg left at the turn of the twentieth century in order to build the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). This was the largest organization in the Second International, the mass socialist network that represents a high point in working-class struggle. A formidable intellectual, she made lasting contributions to Marxism: she launched a revolutionary critique of reformism in the pamphlet Social Reform or Revolution? (1899), expanded upon Marx’s economic analysis in The Accumulation of Capital (1913), and developed a critique of imperialism and militarism as inherent aspects of capitalism. In The Mass Strike (1906), Luxemburg affirmed the revolutionary power of working-class self-activity and traced the inextricable connections between the economic and political at times of heightened struggle. In 1914, when most of the leaders of social democracy abandoned internationalism and supported their respective national war efforts, Luxemburg organized the anti-war opposition, which grew from a minority current to a mass movement of workers and soldiers over the next four years. In all of this she interrogated the economic and political, but also social, cultural, and human dimensions of capitalist exploitation, colonialism, and war. For this work, she was hounded by the state and suffered a series of prison sentences, but also won lasting respect from the socialist movement and workers globally.

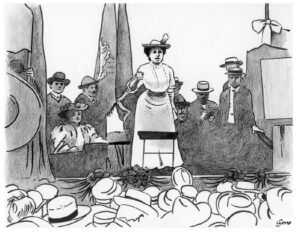

Luxemburg combined class analysis with a sharp awareness of all vectors of inequality and discrimination, drawing on her own experiences as a Jewish Polish woman who lived with a disability. From the beginning of her career in the SPD, even when she was still young and new, she was willing to stand up against the established leaders, parliamentary representatives in particular. Unlike many in the reformist wing of the party, Luxemburg was in constant action, staying close to the mass movement in the workplace and in the streets throughout her life. Popularly known as “Red Rosa,” she was a talented public speaker with a sharp sense of the potency of image, figure, and sound. One of my favorite passages, from a letter of 1898, captures her visceral sense of the political implications of language:

I’m not satisfied with the way in which people in the party usually write articles. They are all so conventional, so wooden, so cut-and-dry … Our scribblings are usually not lyrics, but whirrings, without color or resonance, like the tone of an engine wheel. I believe that the cause lies in the fact that when people write, they forget for the most part to dig deeply into themselves and to feel the whole import and truth of what they are writing. I believe that every time, every day, in every article you must live through the thing again, you must feel your way through it, and then fresh words—coming from the heart and going to the heart—would occur to express the old familiar thing. But you get so used to a truth that you rattle off the deepest and greatest things as if they were the “Our Father.” I firmly intend, when I write, never to forget to be enthusiastic about what I write and to commune with myself. (quoted in Frölich 1972, 56–57)

Her writing and speeches are distinctive for their emotional intensity and figurative innovation.

As Yasuko reflects in the novel, Luxemburg’s life was “unforgettable, especially for the women of the working class,” and she became and remains a point of reference for the left across the world. The probable source of Yasuko’s quote about trampled frogs is a 1917 letter Luxemburg wrote from Breslau Prison to her friend Luise Kautsky (translated into Japanese in the 1920s), in which she wrote: “Dearest, don’t be despondent, don’t live like a little frog that’s been stepped on!” (Adler et al. 2011, 452).1

On her release from prison at the end of World War I, Luxemburg threw herself into mobilizing for the German revolution, but her life was cut short by the forces of counterrevolution. In January 1919 she was detained, beaten with rifle butts, and shot, her body dumped unceremoniously in the Landwehr Canal in Berlin. Her murderers were soldiers of the Noske Guard, precursors of the Nazis, and they were doing the bidding of right-wing leaders of the social democratic government who were intent on reining in the revolution and restoring the capitalist order.

In her extraordinary life, Luxemburg played a leading role in several socialist organizations (often in three different countries at the same time); maintained a prolific publication record in a range of journals and newspapers, in addition to writing numerous books and pamphlets; engaged in endless rounds of public speaking, in venues ranging from party conferences to the mines of Upper Silesia; and put in a lengthy tenure as a loved and respected teacher at the party school.

And yet within all of this, Luxemburg also had a lot to say about the arts. Her writings on literature include formal literary analysis; lengthy discussions, in her letters, of a wide range of contemporary texts and performances; and innumerable references, in her articles, essays, and speeches, to classical and contemporary works. These reveal her familiarity and affinity with a broad and diverse body of texts from the classical to the contemporary, and in several different languages. She did not develop an explicit literary theory, but taken together, her epistolary and formal cultural commentary provide valuable insights for literary analysis: they draw a portrait of literature’s capacity to express, through powerful affect, underlying structural social contradictions; and they remain deeply aware of, and sensitive to, the specificity of the aesthetic realm and the particular qualities of each individual work. In his 2009 assessment of Luxemburg’s literary criticism, social scientist Subhoranjan Dasgupta foregrounds this insistence that works of art must be judged on their own terms, calling it “one of the basic tenets of enlightened Marxian aesthetics … because artistic engagement or literary production always enjoy a high degree of autonomy” (8). Furthermore, creative literature and the arts more broadly occupied a significant location in Luxemburg’s life’s work and can be understood as central to her dialectical materialism and to her vision of human liberation.

Despite their rich potential, Luxemburg’s discussions of literature have not previously received much attention, especially in the English scholarship. Verso Books’ publication of her Complete Works will make it easier to correct this omission. This ambitious, ongoing project is translating the German and Polish archives into English and making them available in a projected seventeen volumes. One of those future volumes will be focused on culture. Those that have already been published indicate the centrality of literary allusions and references to her work.

Even in the economic writings, Luxemburg quotes Boccaccio, Dante, Molière, Schiller, Defoe, and her favorite, Goethe. For example, she quotes a poem by Goethe in a discussion of the reproduction of capital: “The reproductive schema does not purport to present the moment of inception … instead it grasps this process in full flow, as a link in ‘existence’s never-ending chain.’” And in the middle of a complex explanation of surplus value, she reaches for a line from Goethe’s Faust: there is “still ‘a leftover to be carried painfully’” (2016, 389). Luxemburg sometimes refers to fiction to illuminate historical conditions, and at others to crystalize political insights.

In using literature in such ways, Luxemburg is within a long-standing Marxist tradition. Indeed, she sometimes evokes an earlier literary allusion from Marx, in order to suggest a connection between different moments of revolutionary struggle (as in her reference to Ferdinand Freiligrath in Volume 3, 51). It is also apparent that literature was a significant part of the radical working-class subculture of her own day. Luxemburg (2020, 342, 389) describes the first issue of the journal New Life during the 1905 Russian revolution. The issue included a satirical sketch by the writer Evgeny Chirikov, “The Eagle and the Hen,” which supplied a parable for the shifting relationship between the working class and liberals. She later refers to the arrest of Chirikov during the suppression of the revolution, confirming that many of these writers were also themselves revolutionary activists. Luxemburg thus routinely draws on the political potential of literature even as she explores the unique possibilities of the aesthetic realm in its own right.

The letters, collected in a new English edition by Verso in 2011, contain not only references and allusions but also more sustained discussions that reveal important aspects of Luxemburg’s broader approach to literature. Take, for example, her comments in a November 1917 letter to her close friend Mathilde Wurm, written from prison, on Simplicius Simplissimus (a seventeenth-century picaresque novel by Hans Jacob Christoph von Grimmelshausen, the second part of which provided the inspiration for Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children). Here, it is a given that creative fiction can provide unique insight into socio-historical forces. Luxemburg writes of the novel: “It is a vast and powerful portrait of the Thirty Years’ War era, a picture of the barbarization of society in Germany at that time” (443).

Literature is also noted for its visceral emotional impact. Luxemburg (2011, 443) advises her friend “not to read it just now, [because] it would perhaps depress you very much.” But while literature may evoke despair, it can also provide an escape from the world, a form of self-medication, especially at times of acute personal pain. She continues:

I just read it all at one sitting only in order to numb myself and be distracted, because I have been struck a heavy blow: Hans Diefenbach has fallen. I know that life will go on, that one must continue and remain firm and courageous and even cheerful, I know all that—and will soon be done with [grieving] it, all by myself.

This moving passage was composed at a moment of intense personal and political loss, soon after she learned of the battlefield death of her beloved friend and comrade Hans Diefenbach, amid the catastrophic slaughter of World War I. The event is especially distressing in light of Luxemburg’s rich correspondence with Diefenbach, which includes frequent exchange of thoughts and feelings about literature.

Such exchanges also illustrate her recourse to literary fiction at times of adversity. In a July 1917 letter to her friend Sonja Liebknecht (the second wife of Karl Liebknecht, with whom Luxemburg co-founded the Spartacus League in 1918), Luxemburg describes her reaction to a particular verse from Goethe that was running through her head:

It was only the music of the words and the strange magic of the poem which lulled me into tranquility. I don’t know myself why it is that a beautiful poem, especially by Goethe, so deeply affects me at every moment of strong excitement or emotion. The effect is almost physical. It’s as if with parched lips I were sipping a delicious drink that cools my spirit and heals me, body and soul. (qtd. in Dasgupta 2011, 6–7)

This passage typifies Luxemburg’s sharp awareness of the capacity of literature to engage the senses and impact us emotionally in ways that bypass intellectual processes.

These lines—themselves characteristically figurative—indicate that literature’s emotional force derives not only from the explicit content or subject matter, but also, and in some cases solely, from its linguistic and formal qualities. This is Luxemburg responding, in 1909, to a depressed friend who had turned to the works of Alexander Pushkin for comfort during a crisis:

When I was in a situation similar to yours I submerged myself in Krasiński, a Polish poet who you probably do not know. His verses, in their content, are the most trivial rubbish made up of Catholic mysticism, but in their sound they are the purest music, and I was enraptured by them. I read them mostly for their tone and color. (2011, 272)

This attention to the linguistic, imagistic, and audible is a consistent thread running throughout the commentary, along with strongly held and not infrequently scathing critical judgement.

Luxemburg frequently observes that literature is unsuccessful when its content overwhelms its form, or when its explicit social purpose interferes with its artistic integrity. In a 1917 letter from prison to Diefenbach, she writes of her “great, if cool, respect” for the nineteenth-century German dramatist Friedrich Hebbel, but ranks him below other favored playwrights: “He has a lot of intelligence and beauty of form, but there is too little life and blood in his characters, they are to a great extent merely signboards, though cleverly thought out and subtly refined, merely vehicles illustrating particular problems” (2011, 379). In contrast, she expresses “a great love” for the Austrian dramatist Franz Grillparzer, recommending one of his pieces with high praise: “The purest Shakespeare in conciseness, aptness, and popular humor, along with a tender, poetic, touch that Shakespeare doesn’t have” (2011, 379).2 At the same time, Luxemburg had no patience for formal experimentation that is void of meaningful content. In a letter to Sophie Liebknecht from November 1917, she denies being “predisposed against the modern poets,” mentioning several that she enjoys, but confesses: “It is true that in all of them I take somewhat amiss the combination of perfect form with the absence of a grand and noble philosophy. This cleavage between form and substance produces in me an impression of vacancy, so that the beauty of form becomes a positive irritant” (2011, 450). As you can see, she could be a ruthless and cutting critic.

The commentary on Grillparzer suggests another general lesson: long before the formalist objection to the “intentional fallacy” or the much-vaunted postmodern “death of the author,” Luxemburg maintained that the text exists as a separate entity from the person who produced it. The following lines from the letter praising Grillparzer illustrate this, while also showcasing her trademark irreverent and searing humor—in this case leveled not only at the author, but also August Bebel, a much-lauded leading figure in the SPD and the Second International: “Isn’t it laughable that in person Grillparzer was a dry-as-dust government official and quite a boring fellow. (See his autobiography, which is in almost as poor taste as Bebel’s)” (2011, 379). This separation of artist from artwork is habitual, although, in contrast to the formalists and postmodernists, the author as a material fact is often central to Luxemburg’s assessment of a work’s historical and political roots and consequences.

Despite, or maybe because of, the obvious value she placed on creative literature, Luxemburg could be quite caustic about literary criticism. But she did herself produce some formal literary analysis over the span of her life. The examples that are currently available in English include an assessment of the Polish national poet Adam Mickiewicz, first published in the newspaper Leipziger Volkszeitung in 1898; a review of Franz Mehring’s biography of Schiller, which ran in the SPD journal Die Neue Zeit in 1905; the essay “Tolstoy as Social Thinker,” which first appeared as an article in Leipziger Volkszeitung in 1908; and lastly, “Life of Korolenko,” an extensive assessment of the Ukrainian-born Russian author and human rights activist Vladimir Korolenko. This latter work was written in Breslau Prison in 1918 and published posthumously in 1919 as the introduction to Luxemburg’s German translation of the author’s History of My Contemporary.

These pieces, one of which was among the last things she wrote, demonstrate that despite her distrust of the career critic, she did take the analysis of literature seriously. They also include some magnificent examples of writing that showcase Luxemburg at her rhetorical and political best.

The 1898 assessment of Mickiewicz is exemplary. Rory Castle’s (2018) biographical research into Luxemburg’s early life finds that her mother loved this poet, and that Rosa grew up reciting his odes by heart. In this essay the emotional connection is palpable, even while Luxemburg historicizes and contextualizes the poetry. She sets the stage by explaining the rapidly transforming conditions of Poland in the decades following its partition among Russia, Prussia, and Austria at the end of the eighteenth century. In the Russian-occupied areas, the old nobility retained their ruling position: “The ancestral seats of the nobility are still the centers of intellectual and literary life. The magnate is still the patron of the arts, and art, meaning literature, is still either a leisure-hours pastime for the “well-born” dilettante, whether sword-bearing or soutane-clad, or else a form of courtiers’ toadyism” (2009, 2). She argues that this class was only capable of a derivative literature that looked to France, where a “powdery, stilted pseudo-classicism” reigned: “And all that got transplanted to Poland was washed-out copy of that pseudo-classicism, its hallmarks being a smooth, still, hollow form and a total lack of individuality, inner feeling or deep thought” (2009, 12).

But revolutionary change was underway, to be expressed in 1831 in a popular revolt against tsarist Russia. The ensuing challenges to the old order gave rise to a pristine class stratum: a “new intelligentsia” that produced literature not for leisure or the court, but as a profession. These writers looked not to Classicism but to Romanticism. This is Luxemburg’s account of the ensuing clash:

Classicism versus Romanticism: such was the antithesis which, with its roots in art and literature, reached its climax in economics and politics and was soon to reverberate in the clashing swords and rattling gunfire of rebellion. But if victory on the battlefields of Grochów and Praga went to the representatives of the established order—the Russian government—they yet had to draw the short straw on the battlefield of the spirit. While the classicists could offer only shelf upon shelf of a grey mass of mediocrities and soulless manipulators of form, Romanticism, overnight as it were, conjured up whole constellations of glittering young talent from the womb of society, and, as the most brilliant star of this dawn twilight, the mighty genius of Adam Mickiewicz arose in the firmament of Polish literature. (2009, 13)

Not only is this formidable figurative writing in itself—so much is conveyed in the paradoxical “dawn twilight” alone—but it also delivers a trenchant analysis of the reciprocal push and pull between socio-historical forces and cultural developments. One of the striking aspects of this passage is the observation that the opposition appears first in arts and literature, and then is realized in the economic, political, and social realms. Another is the perception that social developments are readable in the very structural, formal qualities of literature. And the last is the recognition that even when the movements that give rise to them go down to defeat on the stage of history—as did the 1831 revolt—traces of those aspirations continue to animate cultural works.

Literature’s revolutionary resonance is a topic to which Luxemburg frequently returns. In her “Life of Korolenko,” she argues that the great movement of nineteenth-century Russian literature “was born out of opposition to the Russian regime, out of the spirit of struggle” (1918, 342). Her review of Franz Mehring’s biography of Schiller notes that “the spread of Schiller’s poetry across the proletarian layers of Germany has, without doubt, contributed to its intellectual elevation as well as its revolutionizing, and to that extent it has, in a way, played its part in the work of the emancipation of the working class” (2009, 17).

Literature, then, may both be generated by and contribute to revolutionary social change.

But Luxemburg rejects any attempt to claim authors or their work as socialist and or revolutionary per se. She writes scathingly of Polish socialists who “try at all costs to derive evidence from Mickiewicz’s writings for his socialist views,” noting acerbically that “this is not an attractive enterprise” (2009, 15). Elsewhere she writes: “Nothing, of course, could be more erroneous than to picture Russian literature as a tendentious art in a crude sense, nor to think of all Russian poets as revolutionists, or at least as progressives. Patterns such as “revolutionary” or “progressive” in themselves mean very little in art. (1918, 345) The relationship between revolutionary social forces and artistic developments is far more indirect, mediated, and contradictory; and it plays out regardless, and often in spite of, the views of the author, as we have already seen with reference to the unfortunate “dry as dust” Grillparzer. Dostoevksy was “an outspoken reactionary,” and “Tolstoy’s mystical doctrines reflect reactionary tendencies”; yet “the writings of both have, nevertheless, an inspiring, arousing, and liberating effect upon us” (345). The reason for this is to be found in the literature itself: “With the true artist, the social formula that he recommends is a matter of secondary importance; the source of his art, its animating spirit, is decisive” (1918, 345).

As this passage indicates, Luxemburg demonstrates the principle that each work of art must be evaluated on its own terms, independently of the author, and not treated schematically as a political treatise. This is not to say that the author is unimportant. Her account of Russian literature points out that many of the greats were not only novelists but also journalists and activists, some of whom used their literary criticism to fight repression and promote progressive ideas. She notes that Korolenko’s committed opposition to the authorities, and in particular to anti-semitic, racist, and xenophobic scapegoating, eventually led him to abandon poetry for journalism.

But there is a powerful recognition that something about the artistic process itself is distinctive and decisive, operating on a level that is independent from the political realm. Luxemburg positions the Russian novel as a genre that offers unique insight into underlying social structures: she writes of the “great and well-rounded view of the world … sensitive social consciousness … the restless search, the brooding over the problems of society which enables it to observe artistically the enormity and inner complexity of the social structure and to lay it down in great works of art” (1918, 346). Here and elsewhere, the suggestion is that the literary fragment can provide insight into the social totality of human relations, albeit in highly mediated and ever shifting ways.

Some comprehension of these processes is offered in her account of the marginalized and the oppressed in the great works of nineteenth-century Russian literature: their focus, in her view, is the impact of social inequality on the human spirit, and “the tragedy of the triviality of the average man.” Those with the least social power—the “criminal,” the prostitute, the disabled, the beggar, the peddler, the child, the minority—in this world of fiction take center stage: “Turgenev, Uspensky, Korolenko, and Gorky took up these ‘stranded’ folk, the criminal as well as the prostitute, with a broad-minded realism, as equals in human society, and achieve, just because of this genial approach, works of a high artistic effect” (1918, 349).

Luxemburg traces these qualities back to the reigning conditions of class struggle: the “opposition to the Russian regime … the spirit of struggle … explains the richness and depth of its spiritual quality, the fullness and originality of its artistic form, above all, its creative and driving social force. Russian literature became, under czarism, a power in public life as in no other country and in no other time” (1918, 342).

This appreciation of the liberating potential of literature coexists with the clearest understanding that literature, and all culture, is a product of class society and could not exist without the exploitation of the producing class, who are yet largely excluded from its enjoyment. Luxemburg’s 1908 discussion of Tolstoy’s writing on art is illuminating on this question. Tolstoy’s commentary is historically bounded: the subject here is “high art” before the mass culture of modernity, but the implications are nonetheless germane. For Tolstoy, Luxemburg writes, “art—contrary to all aesthetic and philosophical scholastic opinions—is not a luxury product for releasing feelings of beauty, joy or the like in beautiful souls, but an important historical form of social communication, like language between people” (2009, 24). Proceeding from what Luxemburg calls this “genuinely materialist and historical criterion,” she summarizes Tolstoy’s argument:

The whole of existing art is, with very few small exceptions, incomprehensible to the great mass of society, that is to say, to working people. Instead of concluding from this with the customary view that the great masses are intellectually coarse and need to be “raised” to understand contemporary art, Tolstoy reaches the opposite conclusion: he declares existing art to be “false art” … ever since society has been split into a great exploited mass and a small ruling minority, art only serves to express the feeling of the rich and leisurely minority. (25)

Luxemburg has great admiration for this, noting that “there is a real revolutionary radicalism when he smashes the hopes that reduction in working hours and improving education among the masses will create understanding of art,” seeing instead that “art … is necessarily based on the oppression of the masses and … it can only be sustained by sustaining this oppression” (25). She contrasts Tolstoy’s materialism with the idealism of the reformists in the SPD: “The writer of this is every inch more of a socialist, and an historical materialist too, than those party members mixing with the latest artistic crankiness who want, with thoughtless zeal, to ‘educate’ Social Democratic workers to an understanding of the decadent daubings of a Slevogt or a Hodler” (25).3 Luxemburg detects an error, however, in Tolstoy’s static understanding of class: failing to understand the fluidity of class society, and lacking any sense of the proletariat as agent of change, Tolstoy thus belongs with the “great utopians of socialism” (26).

In the 1903 essay “Stagnation and Progress of Marxism,” Luxemburg tackled head-on this question of the class ownership of culture: “In every class society, intellectual culture (science and art) is created by the ruling class; and the aim of this culture is in part to secure the direct satisfaction of the needs of the social process, and in part to satisfy the mental needs of the members of the governing class.” While in earlier periods, emergent ruling classes could develop new artistic and scientific cultures to assist their aspirations, the proletariat—a “non-possessing class”—cannot follow this path: “It cannot in the course of its struggle upward spontaneously create a mental culture of its own while it remains in the framework of bourgeois society. Within that society, and so long as its economic foundations persist, there can be no other culture than bourgeois culture.” She continues, “Notwithstanding the fact that the workers create with their own hands the whole social substratum of this culture, they are only admitted to its enjoyment insofar as such admission is requisite to the satisfactory performance of their functions in the economic and social process of capitalist society” (1970, 110).

The oppressed cannot create their own culture under the conditions imposed by capitalism and are largely excluded from the enjoyment of the existing arts. But culture is nonetheless deeply important to the project of emancipation: “The utmost [the working class] can do today is to safeguard bourgeois culture from the vandalism of the bourgeois reaction, and create the social conditions requisite for free cultural development” (1970, 110). This notion of the oppressed as protectors and inheritors of culture infuses Luxemburg’s commentary. So too does the recognition that literature can carry traces of the aspirations and struggles of the exploited. In her scornful rejection of attempts to claim Adam Mickiewicz as a socialist, Luxemburg affirms the value of his poetry for the working-class movement: “The enlightened proletariat is surely intellectually mature enough to love and honour this great poet for his poetic genius without needing an inducement for the unclear mystical-utopian social imaginings of his period in decline. The class whose goal is the renewal of the world can have no such narrow horizons” (2009, 16).

As discussed earlier, Luxemburg argues that Schiller’s poetry has “in a way played its part in the work of the emancipation of the working class,” but this is qualified:

Schiller’s role in the intellectual growth of the revolutionary proletariat in Germany is not so much rooted in what he himself imported into the working-class struggle for emancipation through the content of his poems, but rather the reverse: it consists in what the revolutionary working class deposited in Schiller’s poems based on its own world-view, its striving and its feelings (2009, 17).

This process is multi-stranded and takes place at sites of both production and reception: previous moments of class struggle found their way into Schiller’s poetry, and contemporary movements create readers who are able to make use of it now.

Luxemburg’s position is close here to that developed by Walter Benjamin in the 1930s: Benjamin famously avowed that “there is no document of culture which is not at the same time a document of barbarism,” but he also looked to culture for glimpses of “a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed past” (quoted in Löwy, 95). Like Benjamin, Luxemburg uncovers the barbarism behind the cultural treasure, revealing the history and continuity of exploitation and expropriation that make it possible. And, also like Benjamin, Luxemburg nonetheless finds therein traces of the traditions of the oppressed.

All of this is apposite to contemporary literary debates. The current renewed interest in Luxemburg has started to expand into postcolonial studies, my primary field, and can be seen in publications such as Rosa Luxemburg: Capitalism, Imperialism, and the Postcolonial, a 2018 special issue of New Formations that considers the contemporary global relevance of Luxemburg, and the 2021 collection Creolizing Rosa Luxemburg, an exploration of her significance for current feminist, anti-racist, and decolonial struggles.

While the full significance of Luxemburg’s cultural writings has yet to be registered, her recognition of the paradoxical push and pull of creative literature speaks to contemporary debates in the context of both a resurgent far right and mass movements against systemic racism. In her new book, Azadi: Freedom. Fascism. Fiction, Arundhati Roy identifies the specific literary qualities that can offer alternatives to the “fake histories” associated with right-wing ideology:

The foundation of today’s fascism … rests on a deeper foundation of another … more sophisticated set of fake histories that elide the stories of caste, of women, and a range of other genders—and of how those stories intersect below the surface of the grand narrative of class and capital. To challenge fascism means to challenge all of this … fiction is uniquely positioned to do this, because fiction has the capaciousness, the freedom and latitude to hold out a universe of infinite complexity. (Roy 2020, 150)

Roy rejects any tendentious or instrumental approach—“fiction as exposé, or as the righter of social wrongs … fiction that is a disguised manifesto or written to address a particular issue or subject” but looks rather to the novel’s ability to “recreate the universe of the familiar” (150–51).

Luxemburg’s analysis continues to provide insight into these contested and contradictory forces. As one would expect from such a formidable dialectician, she traces the multifaceted relationships between historical and cultural developments, unearthing the violent roots of literature, and insists that each work is more than simply the sum of its socio-historical parts, but must be appreciated on its own terms, according to the particular elements of genre and form. Balancing materialist contextualization with a sharp recognition of the aesthetic, the sensual, and emotional affect, Luxemburg thus offers an alternative to the pitfalls of idealist literary criticism—in which textual analysis takes place in a vacuum without reference to the structural inequalities that are the precondition for cultural production—and ideology critique—which reduces literature to anthropology or unwitting political testimony. And while insisting that socialists do not need political cover to appreciate art, she points to the ineffable potential for literature to imagine possible alternatives, to capture and nurture “the spirit of struggle.”

A version of this essay was presented as a lecture for the UW–Madison Havens Wright Center for Social Justice on October 29, 2020. This was developed from a talk at the International Rosa Luxemburg Conference in Chicago in April 2018 entitled “‘Like a flash from eternity’: Rosa Luxemburg and Postcolonial Literature.”

Bibliography

Adler, Georg, Peter Hudis, and Annelies Laschitza, eds. 2011. The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg. Verso.

Castle, Rory. 2018. “‘All the Hidden, Bitter Tears’: Family, Identity and the Shaping of Revolutionary ‘Red Rosa.’” Internationale Rosa-Luxemburg-Gesellschaft, Chicago.

Dasgupta, Subhoranjan. 2009. “Rosa Luxemburg’s Critique of Creativity and Culture.” Institute of Development Studies Kolkata, May.

Frölich, Paul. 1972. Rosa Luxemburg: Ideas in Action. Trans. Joanna Hoornweg. London: Pluto.

Kobayashi, Takiji. Yasuko (1931). In The Crab Cannery Ship and Other Novels of Struggle. Trans. Zeljko Cipris. University of Hawaii Press, 2013.

Löwy, Michael. 2005. Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s “On the Concept of History.” Verso.

Luxemburg, Rosa. 1918. “Life of Korolenko.” Marxists Internet Archive.

———. 1970. Rosa Luxemburg Speaks. Pathfinder.

———. 2009. Selected Political and Literary Writings. Michael Jones, ed. London: Merlin.

———. 2016. The Complete Works of Rosa Luxemburg. Vol. 2. Peter Hudis, ed. Verso.

———. 2020. The Complete Works of Rosa Luxemburg. Vol. 3. Peter Hudis, ed. Verso.

Roy, Arundhati. 2020. Azadi: Freedom. Fascism. Fiction. Haymarket Books.

Notes

1. Thanks to James Holstun for first drawing my attention to this passage, to Peter Hudis for helping me to trace the quotation to the letter, and Rida Vaquas for contextualizing the translation history of Luxemburg in Japan and her status in the Japanese proletarian novel.

2. In the letter, Luxemburg refers to this work as Judith, but the editors of The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg point out that in fact, “Luxemburg was referring to the fragment by Grillparzer entitled Esther” (2011, 379n664).

3. Max Slevogt was a German impressionist painter; Ferdinand Hodler was a well-known Swiss painter.