The End of the “American Century”: Whither US Global Hegemony and the Indispensable Nation?

“This is the end, my only friend, the end/Of our elaborate plans, the end/Of everything that stands, the end/No safety or surprise, the end.” – Jim Morrison, The Doors

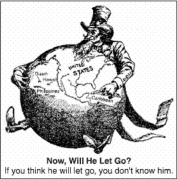

Will Donald Trump’s ascension to the imperial presidency mark the nadir of the declension of the United States as the global hegemon? While Trump’s fantasies about “making America great again” do not explicitly rely on promoting the US as the “indispensable nation,” they, nonetheless, deploy strategies to resurrect the fossil fuel driven expansion of the military industrial state that marked the post-World War II period of US global dominance. Does Trump’s criticism of NATO and “nation building” suggest a less interventionist foreign policy, or does his commitment to white nationalism still augur a redeemer nation, primed to contest those who would challenge US global hegemony? Given the present contradictions of US global hegemony and the policies and posturing of a Trump and his proposed Administration, are we witnessing the end of the American Century and its institutional and ideological commitment to the US as the “indispensable” nation?

Although the emergence of the United States as a global hegemon had roots in national and international conditions prior to World War II, that war provided the US with the historical opportunity to establish its global hegemony. US global hegemony was not only a consequence of economic, political, and military domination, but also a reflection of the cultural and ideological orientations that advanced US moral and intellectual leadership. Among the ideological orientations that attempted to foist US hegemony on the rest of the world was the articulation of the “American Century.” On the eve of the US entry into WWII, Henry Luce, editor and owner of Time-Life magazines, proclaimed the American Century in the pages of Life. Incorporating long-standing beliefs in the United States as a redeemer nation compelled to engage in messianic missions in the world, Luce assumed that the US was the true inheritor of the best that civilization (i.e., white and western) offered.

Luce’s vision of the American Century was predicated on the belief that the US had both the natural right and ordained responsibility to wield political and military power as a guarantor of progress and prosperity throughout the world. According to Neil Smith, “US global dominance was presented as the natural result of historical progress, implicitly the pinnacle of European civilization, rather than the competitive outcome of political-economic power” (American Empire, 20). Hence, US policymakers sought to establish US pre-eminence by overt and covert means. Among the overt designs were numerous international and multinational organizations, such as the United Nations, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. The covert means focused primarily on the role of a newly created Central Intelligence Agency to foster favorable governments around the world. Although US interventions had predated the operationalizing of the American Century, those foreign adventures increased during the Cold War.

The proponents of a muscular intervention in the world found inspiration in the resonant words of President John Kennedy “to bear any burden” and “pay any price” for spreading freedom. However, such intervention came to a crashing halt in the Vietnam War, causing a crisis in what had been the “triumphalism” embedded in the American Century. With the defeat of the US in Vietnam and other American political and economic setbacks throughout the 1970’s, it seemed as if the American Century was on the wane.

On the other hand, the ideologues of the Reagan Administration loudly proclaimed their intention to restore American pre-eminence in the world. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, these ideologues confronted a dual challenge to their desire for what would later become the Bush doctrine of unilateral pre-emptive war and “full spectrum dominance” (as articulated in the 2000 version of Project for a New American Century): first, how to sustain and expand the military-industrial complex that was the core of US dominance: and second, how to convince the American public to support military interventions for strategic purposes.

Raising questions and concerns about imperial overreach against the backdrop of revitalizing the American Century in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, invariably highlights the degree to which such an ideological formulation was and is a “benevolent” form of imperialism, or, in the liberal variation of this, humanitarian intervention. Indeed, one can find those policymakers in both liberal and conservative administrations, from Madeline Albright to Condolezza Rice to Hillary Clinton, who still regard the United States as the indispensable nation, believing in its universalizing mission. Against the backdrop of economic competitors and global realignment, this indispensability appears, nonetheless, to be in terminal decline.

An attempt to staunch that decline through financialization, corporate globalization, and neoliberal foreign and domestic policies took another hit with the economic crises of 2008. However, the precipitous decline in pre-eminence of the production of manufactured goods from a high point of 60 percent in 1950 to about 25 percent at the end of the twentieth century cannot be halted by the kind of flim-flam tax breaks by Trump and Indiana to industrial manufacturers like Carrier and its parent company, United Technologies, the billion dollar Pentagon profiteering corporation. Although the United States had dominated industrial production in electronics and electrical equipment at mid-century, by the beginning of the twenty-first century, non-US corporations occupied nine out of the top ten positions. Even in the banking sector, nineteen of the top twenty-five banks in the world were located outside the United States.

While the dollar still remains the primary reserve currency in the world (with growing challenges by Russia and China to the dollar), the recent massive international financial failures are a direct result of the financialization that was promoted by US interests from the 1970s onward and continue to play an outsized role in policies of the federal government irrespective of which party is in power. As a consequence of those toxic financial arrangements, uprisings against the banksters in various countries, from Iceland to Latvia, Greece to Martinique, had led to challenges to the flawed logic of US-dominated financialization.

The national security and warfare state that Trump wants to prop up is incapable of subduing the very chaos that it contributes to around the globe. As prophetically noted by French critic Emmanuel Todd at the start of the Iraq War in 2003: “the United States is pretending to remain the world’s indispensable superpower by attacking insignificant adversaries. But this America – a militaristic, agitated, uncertain, anxious country projecting its own disorder around the globe – is hardly the indispensable nation it claims to be and is certainly not what the rest of the world really needs now” (After the Empire, xviii).

Trump’s intended employment of generals (Flynn, Mattis, and maybe Petraeus) associated with the debacles in Iraq and Afghanistan suggest at best an arrested development of that warfare state. In his trenchant criticism of the military brass in books and articles, Andrew Bacevich has emphatically highlighted the failures of Washington’s war machine, a machine that has little hope of repair even with the hypermilitarism of the ruling Republican Party. As Bacevich contends in The Limits of Power: “How is it that our widely touted post-Cold War military supremacy has produced not enhanced security but the prospect of open-ended conflict? Why is it that when we flex our muscles on behalf of peace and freedom (sic), the world beyond our borders becomes all the more cantankerous and disorderly” (156).

While Trump appears to be drawing back from the confrontation promoted by Obama and Clinton with Russia, he has not hesitated to encourage aggressive postures towards China, Iran, and Cuba. It is hard to imagine that a Trump presidency would not embrace the kind of imperial policies and gestures that continue to make the US an outlier in the international community. Moreover, as Eric Hobsbawm has argued in On Empire: “There is no prospect of a return to the imperial world of the past, let alone the prospect of a lasting global hegemony, unprecedented in history, by a single state, such as America, however great its military force. The age of empires is dead. We shall have to find another way of organizing the globalized world of the twenty-first century” (25).

The xenophobic and racist nationalism embodied by Trump cannot avoid pronouncements and policies that generate arrogance and aggression towards people of color around the world and in the US. An “America that continues to relate to the world by a unilateral assertion that it represents civilization,” opines Immanuel Wallerstein in The Decline of American Power, “cannot live in peace with the world, and therefore will not live in peace with itself…Can the land of liberty and privilege, even amidst its decline, learn to be a land that treats everyone everywhere as equals” (215)?

Trump’s assertion that a wall must be built on the Mexican border with the US, even in the face of diminishing numbers that have any desire or need to enter the country, resonates with many of his followers who are fearful and paranoid about the hordes of brown-skinned others already among us. But as Barbara Kingsolver observes in Small Wonder about the metaphoric wall spawned by imperial and narcissistic enclosures: “The writing has been on the wall for some years now, but we are a nation illiterate in the language of the wall. The writing just gets bigger. Something will eventually bring down the charming, infuriating naiveté of Americans that allows our blithe consumption and cheerful ignorance of the secret ugliness that bring us whatever we want” (262-3).

Everywhere that US nationalism and imperialism will try to build walls growing bands of insurgents, migrants, and miscreants will undoubtedly scale those walls. Identifying with those who seek to tear down such walls, let us recall the lyrics of a song by Los Lobos, that driving rock band from East LA: “Some day that wall will tumble and fall/And the sun will shine that day.” For that day to come, however, acts of intervention must be undertaken. As stated eloquently by Rebecca Solnit in Hope in the Dark: “Blind faith faces a blank wall waiting for a door in it to open….The great liberation movements hacked doorways into walls” (13-14).

Although political will and popular resistance is essential to combating any imperial or nationalist pretensions of the new Trump Administration, it is also becoming quickly apparent that this regime, especially in relation to environmental issues, will become an outlier in the international community. No longer capable of providing the kind of moral and intellectual leadership necessary to maintaining hegemony, the United States will inevitably degenerate into a rogue nation – at best dispensable and at worst a threat to humanity and the planet.