The Arab Winter as "Morbid Symptom"

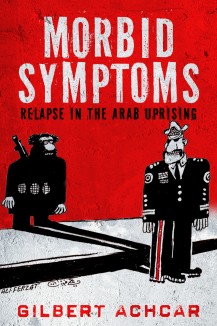

Gilbert Achcar, Morbid Symptoms: Relapse in the Arab Uprising. Stanford: Stanford Univeristy Press, 2016. 240 pp. $21.95.

The title of Gilbert Achcar’s latest book is derived from Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born, in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear”.

Although written as a sequel to his previous – and more detailed – book, The People Want, Morbid Symptoms qualifies as a stand-alone work of immense importance in its own right. Focusing largely on Syria and Egypt, ‘Morbid Symptoms’ skillfully explains the mutation of the ‘Arab Spring’ – though Achcar prefers the term ‘uprising’ – into an ‘Arab Winter’.

Contemptuously rejecting the culturalist explanations of the Arab world’s democratic deficit, Achcar foregrounds two key factors to describe the mutation of the ‘Arab Spring’ into an Arab nightmare. First, he highlights the patrimonial and rentier character of the Arab states caught in the whirlwind of ‘Arab Spring’. Achcar argues that not only were the optimistic perspectives projected in 2011 proved to be flawed, a comparison with the fall of Stalinist regimes across eastern Europe in 1990 was equally problematic because these perspectives and analogies ignored, among other factors, the character of the Arab states.

Historically, the exceptional state system in the East European countries was dominated by bureaucracies instead of propertied classes. Bureaucrats in these states could sense an improvement in their privileges. In fact, top bureaucrats could contemplate “their own transformation into capitalist entrepreneurs” under market capitalism. Hence, a relatively peaceful change.

In most Arab states, “ruling families ‘own’ the state… to all intents and purposes, they will fight to the last soldier in their praetorian guard in order to preserve their reign”. According to Gilbert, these states are run by an interlocking trilateral ‘power elite’ – consisting of military and political institutions, and the state bourgeoisie – whereby every segment of the power elite is bent upon fiercely defending its access to the state, the main source of privileges and profits.

This also explains the different trajectory of the Arab Spring in Tunisia/Egypt and Libya/Syria. In the former cases, the states were dominated by institutions. In the latter, the states had become family fiefdoms. In Tunisia/Egypt, institutions let go of individuals (Mubarak and Ben Ali) when they became liabilities in order to preserve institutional integrity.

The second factor that catalysed the mutation of the ‘Arab Spring’ into an ‘Arab Winter’, claims Achcar, was a situation of: “one revolution: two counter-revolutions’. In this equation, the ancienregimes constituted one counter-revolution while the other was such regional powers as Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Iran. This regional dimension of counter-revolution has translated into the ascendency of Islamic fundamentalism lavishly bankrolled by these three countries. A mutual rivalry between these three patrons of Islamic fundamentalism further complicated the situation leading to “the highly convoluted development of the Arab revolutionary crisis, compared to which most other revolutionary upheavals in history look rather uncomplicated”.

Syria epitomises these complexities where a ‘secular and socialist’ (at least an original self-designation) Ba’athist regime has been shored up by Iranian Ayatollahs and the Hezbollah, apparently on sectarian grounds.

The Alawite Assad regime, in turn, has facilitated the rise of Isis, a fanatical, anti-Shia force targeting Iraq – also Tehran’s ally since 2005. In fact, Isis has been Syria’s “preferred enemy”, says Achcar. Ironically, Isis is also a thorn on the side of the Saudis. Consequently, the House of Saud has re-adopted its estranged violent child: Al-Qaeda – at least, in Syria.

The Kurdish resistance against Isis and their control of Rojava forced Turkey to support Isis, at least tacitly and temporarily. Ankara, along with Doha, has been supporting the Muslim Brotherhood while the Syrian Brotherhood and Isis have been at daggers drawn. However, Erdogan – under US pressure – also facilitated the Kurdish resistance (another complex story) against Isis.

The irony is that Assad and allies (Russia, Iran, Hezbollah) as well as their rivals (Saudis, France, the US, Turkey) have been pounding Syria in the name of fighting Isis (Achcar explores these paradoxes). However, none of them has seriously engaged Isis. In the process, an unbearably heavy price has been paid by the Syrian people. Achcar describes it as the “abandonment of [the] Syrian people”.

First, the Syrian people have been abandoned by the superpowers, notably the US. Achcar shows that the Syrian resistance, often ridiculed by knee-jerk ‘anti-imperialists’ as a US proxy, has been abandoned by Washington. The US policy, argues Achcar, has been guided by two concerns: the Iraq experience and Israel.

In view of its Iraq misadventure, Washington single-mindedly pursued a Yemen-like solution in Syria. The idea was to retain the Ba’athist apparatus minus Assad. This policy not only proved to be counter-productive, but also inflicted a heavy toll on the Syrian masses. Second, Washington did not adequately arm the resistance in view of Israeli security; weapons capable of downing Assad’s jets might tomorrow be deployed to hunt down Israeli jets.

Achcar also points out the abandonment of the Syrian people by the knee-jerk ‘anti-imperialists’. “When disastrous failures of imperialism happen at the cost of terrible human tragedies, there can be no schadenfreude from a truly humanist anti-imperialist perspective”. Before pointing out the confused silence of these anti-imperialists over US support for Kurdish forces, he wonders why the US arming the Syrian opposition is so harshly judged. Is it that anti-imperialists want US support only when their favourite troops are leading the fight?

For the attention of puritan ‘anti-imperialists’ in the Muslim world, this reviewer would also suggest they pay keen attention to the role of brotherly Muslim countries (Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar), assiduously documented by Achcar, in destroying Syria (and Libya). Likewise, for the attention of secular supporters of the Assad regime, Achcar has sizeable evidence not only on the murderous character of the Assad regime but also on how the primary responsibility for the Syrian tragedy lies with Bashar. The Ba’athist regime turned a peaceful intifada into a military affair. It also orchestrated inhuman hunger-sieges and massacres. For instance, of 56 sectarian massacres, 49 were conducted by the Ba’athist regime and its allies.

In comparison, the march from Tahrir Square to the presidential palace in Egypt was a cakewalk. The relatively peaceful overthrow of the Egyptian pharaoh five years ago did not owe to any Gandhian inclinations he espoused. As mentioned above: unlike Syria and Libya, Egypt is not owned by a family. Rather, an institution (the military) dominates the state.

When Mubarak became a liability, he was sent packing. The military stepped back, only to recuperate and stage a comeback. While Achcar analyses the Morsi government’s disastrous policies as well as the disastrous role of the Egyptian Left in facilitating-by-default the counter-revolution, what might intrigue is the performance of Brother Morsi as president.

The Brotherhood’s apologists have been casting Morsi as an anti-Zionist and anti-American leader, overthrown unjustly through Washington’s machinations. Here is a brotherly chutzpah: On becoming president, Morsi wrote to his “great and dear friend” Shimon Peres to express his “strong desire to develop the affectionate relations that fortunately bind our two countries”, while wishing Israel “prosperity”.

Originally posted here.