A Preview of “What is Post-Modern Conservatism?: Essays on Our Hugely Tremendous Times”

What is Post-Modern Conservatism: Essays on Our Hugely Tremendous Times is going to be released later this year by Zero Books. Some of the pieces in this collection were originally printed in New Politics. The collection will include additional articles on the cinema of Dinesh D’Souza by David Hollands, Marxist theory by Borna Radnik, the influence of digital technologies and reactionary paranoia by Dylan de Jong, Walter Benjamin and the alt-right by Erik Tate, and the rise of neo-masculinity by Conrad Hamilton.

What is Post-Modern Conservatism: Essays on Our Hugely Tremendous Times is going to be released later this year by Zero Books. Some of the pieces in this collection were originally printed in New Politics. The collection will include additional articles on the cinema of Dinesh D’Souza by David Hollands, Marxist theory by Borna Radnik, the influence of digital technologies and reactionary paranoia by Dylan de Jong, Walter Benjamin and the alt-right by Erik Tate, and the rise of neo-masculinity by Conrad Hamilton.

We are very appreciative of the support given to us by Dan La Botz and the other editors. In these trying times, when various forms of post-modern right wing populism are ascendant across the globe, it is exceptionally important for leftists to have robust theoretical and practical debates over what we are facing and how to push back.

We’ve recently begun presenting on the text in a number of different formats, and prepared this brief article to summarize the many arguments and themes for those who may be interested in reading our in its entirety when it comes out. Those who find the thesis particularly interesting may wish to pick up a copy when it comes out. Additionally, those who are provoked by the account presented my appreciate the more academic monograph The Rise of Post-Modern Conservatism, which is exclusively written by me and will be published with Palgrave MacMillan at the end of the year.

Neoliberal Society and Post-Modern Culture

The underpinning thesis of the book is that the emergence of post-modern conservatism can be explained as a reaction to the social, economic, and technological transformations of neoliberal society and the profound destabilization of our sense of time, space, and identity expressed by the aesthetics of post-modern culture. This produced a reactionary drive on the part of many individuals, who reconstituted their political sense of self as a pastiche of different identities who traditionally wielded significant power in the past. Post-modern conservatives then turned to leaders who promised to retrench the power of their followers while cracking down on their perceived enemies, who were blamed for the transformations of neoliberal society and sense of destabilization associated with post-modern culture.

Neoliberal societies emerged in the late 1970s, often being presented as an ideological alternative to the excesses of the Keynesian welfare state and the various civil rights movements active through the 1960s. The gambit of neoliberal apologists such as Milton Friedman and F. A. Hayek was that citizens would accept the inequality, precarity, and anti-democratic tendencies associated with neoliberalism, so long as they were compensated with improvements in their individual quality of life driven by economic growth and technological innovation. As neoliberal governance became ever more hegemonic, this gambit was perpetuated as many apologists ignored the deepening social, economic, and technological transformations which saw their traditional societies “melt into the air” to use Marx and Engels’ famed expression. Socially neoliberalism brought with it profound demographic changes accompanied by the imposition of ever greater restrictions on democratic participation. Economically greater inequality was not matched by improving standards of living for all, but often by greater precarity and declining relative incomes for members of society who were already vulnerable. And technologically society witnessed the emergence of immense new ways of communicating and engaging politically. Many of these were extremely valuable, but they also enabled the growing dissolution of what Jürgen Habermas called the “public sphere” in favor of hyper-partisan communication bubbles where individuals were fed a steady diet of conspiracy theorizing and antagonism.

Many of these transformations were explicated in the products of post-modern culture, which articulated the sense of unease and destabilization that took place during the period. More specifically, post-modern culture was characterized by tremendous changes in our relationship to space and time. The world came closer together through forms of economic and technological integration, sometimes completely transforming the urban spaces many inhabited over the course of a lifetime. But rather than leading to a greater sense of inclusion and solidarity, these spatial-temporal shifts often highlighted how fractured the world still was and how many people were still left behind. More deeply, the Francis Fukuyamist sense that “history proper” had come to an end brought about a tremendous loss of meaning in a world where political theologies had often taken the place of religious ones. As Mark Fisher rightly observed in his classic Capitalist Realism, the art of the time expressed the anomic belief that it was easier to imagine the end of the world than to picture a world without (neoliberal) capitalism and its injustices. The belief that the time of history had given way to the time of billable hours, and that genuine change was simply impractical led to tremendous anxiety. Sometimes this even led to anger at the Margaret Thatcher/Tony Blair insistence that there was “no alternative” to the status quo of neoliberal capitalism, occasionally with a more human face.

At the same time, post-modern culture constituted the climax of an ongoing crisis of identity which had been gestating since the Romantic era. As neoliberal governance transformed our societies and post-modern culture demonstrated the changes in our living spaces, the “sources” we used to constitute our sense of self and belonging were gradually eroded. In some respects this was an emancipatory development, as it opened doors for the creative development of new or previously marginalized identities and attached forms of political agitation. Many of these new or previously marginalized identities rightly used the destabilization provoked by post-modern culture to agitate for greater political inclusion and toleration. We obviously by no means intend to dismiss these progressive achievements. But it is important to draw attention to the many individuals who experienced the destabilization of identity as a tremendous loss; one thinks of Nietzsche in his more apocalyptic ruminations about the death of God. For these individuals left adrift in post-modern culture without a clear sense of identity, the reactionary temptation offered by post-modern conservatism would prove very great.

Who Are the Post-Modern Conservatives?

Post-modern conservatism appealed to these individuals not because it constituted a return to a form of authenticity available to a previous era, but first and foremost because it was a “hyperreal” reaction to a society and culture that had left too many behind. The first characteristic of post-modern conservatives is a tendency to construct through association with identities which had previously wielded tremendous political power, but who were increasingly just another set of players in the process of neoliberalization. Often times this was carried out in conjunction with others through new technological media such as the Internet. Post-modern conservatives formed what Jameson would call a pastiche of an identity; one which had little integrity to it, but was forged from the symbolic tropes associated with authorities past. Ethnicity, religion, nationality, gender, and even race were all creatively assembled into this pastiche, often will little discrimination about the incompatibility of these various identities. The particularity of being a white male American was compensated for with the sense that one was the bearer of a universal Western Christian civilization which had been unjustly criticized by those who could not understand its greatness.

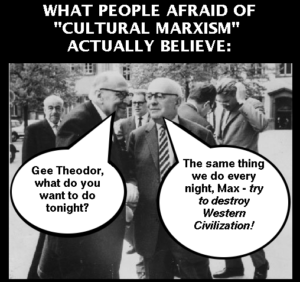

This brings us to the second characteristic of post-modern conservatives, which is their tendency to frame their political allegiances primarily in terms of reactionary opposition. As Corey Robin observes in his The Reactionary Mind, conservatives of all stripes have often framed their politics primarily as opposition to changes in a privileged hierarchy. This was certainly the case with post-modern conservatives, who reacted strongly to the claim that a shadowy collection of progressives-feminists, multiculturalists, so called cultural Marxists etc-were responsible for eroding their rightful place in society as male, white, meritocrats. The substantial programs they tended to support were less about rectifying the inequities and social conditions of neoliberal society and post-modern culture, and more about crushing or marginalizing the efforts of these enemies. Post-modern conservatives were therefore very willing to turn to authoritarian aristocrats like Donald Trump or Boris Johnson is they promised to use political power to crack down on these opponents and elevate the pastiche of identities they cherished. The results of this development are now very clear.

Conclusions

All of these themes are explored in considerably greater detail in the book(s), which we hope will provide some theoretical guidance to leftists trying as we are to understand the rise of right wing politicians across the globe. Obviously it is easy to lose faith in the face of such developments. Fortunately there does seem to be some dialectical push back against the rise of post-modern conservatism, and many of these movements are daily gaining steam. While it might be too much to agree with Slavoj Žižek that the rise of the right is largely an opportunity for the left, he is no doubt correct that greater discursive space is now available to push for more dramatic changes to the neoliberal consensus. We are starting to witness some of this with the emergence of politicians like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the intractability of Bernie Sanders’ efforts in the Democratic Party. Our hope is that these positive trends will deepen and continue into the future, leading eventually to the decline and fall of post-modern conservatism.