The high point of social radicalism in America was the Continental Congress of Workers and Farmers for Economic Reconstruction in Washington, DC on May 6 and 7, 1933. Delegates came from around the country in response to the call from a few hundred prominent established leaders of unions, farmers’ organizations, cooperatives, the Socialist Party, student groups, organizations of the unemployed. Signers of the call came from thirty-one states and the District of Columbia. Every organization invited to attend was asked to send two representatives. In response, over 4,000 delegates rallied to the nation’s Capitol.

A defiant declaration by one union leader, entitled “Labor on the March,” introduced the official call:

“We shall fight with every legitimate weapon at our command. We are in earnest. We shall want every friend and every right-thinking American to help. But we do not intend to forewarn the money-fat enemies of America who, through one device or another, have wrung from the people such a proportion of the fruit of their toil that they are stranded in a motionless sea of unemployment…. Here we take a stand and here we fight, such a battle as no labor movement has ever fought before. We fight a battle …that shall take from the pillaging band of exploiters the weapons with which they have stricken down our millions. We prefer the council table, but we do not shun the battlefield. I am ready to lead the hosts of labor into a battle which we are determined to carry to the last possible ounce of our strength, not for the sake of conquest but for the sake of justice. The die is cast for the battle out of which labor expects a new America.”

The author of those ringing words? William Green, President, American Federation of Labor.

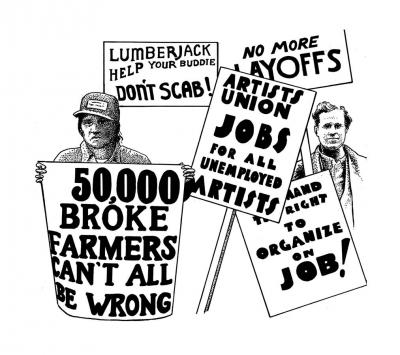

After more than three years of deep depression, the delegates confronted a capitalist system in collapse. Unemployment was estimated at 25 percent, although no one was actually counting; long charity-financed breadlines snaked the streets; evicted tenants saw their possessions piled on sidewalks; destitute farmers poured gallons of milk onto the roads in a desperate “National Farmers Holiday” movement; no safety net, no unemployment insurance; no security—social or otherwise.

And they came to Washington not merely to protest injustice but to create a continuing new national organization to battle for justice. The very title of their conference revealed the scope of their intentions. Continental Congress! The first Continental Congress of 1775 prepared the way for revolution against England. The Continental Congress of 1933 would prepare the way for a new social system. For the labor movement, this was a momentous event in history. For our country, it was a fork in the road never taken, a significant what-might-have-been but for….

I can remember only a single inadequate and derogatory reference to this moving, this emotional event: David Shannon, in his book on the Socialist Party, shrugged it off as a “gimmick.” How do I know what really happened? That it was more than an imaginative dream? Because I was there. At 17, I was a delegate from the Student Forum, a club established by members of the Young Peoples Socialist League at CCNY, one loosely affiliated to the League for Industrial Democracy. My mind was jogged when I ran across a copy of the official conference minutes among old misfiled papers. This account is based upon those minutes, only slightly seasoned by memory. All quotations are from those minutes.

It is impossible for me to do justice to what was so noteworthy an event in labor history. I have no access to research facilities. Surely documents, personal memos, releases, and news accounts are buried in the archives of universities. Mine are at Wayne University. My intention here is to rescue the bare facts from oblivion in the hope others, more qualified than I, can carry the story further. This was no media gimmick. Nothing that I write here can reproduce the excitement, the enthusiasm, and the sense that something momentous was in the making.

Four speakers opened the sessions with rousing speeches that set the tone.

First came Emil Rieve, International President of the Hosiery Workers, who served as Conference chairman. Taking as his theme the Declaration of Independence, he declared:

“The author of the Declaration of Independence …. set forth that when any government failed to achieve such life and liberty, it was the right of the people to alter or abolish it…. At the present time, no less than 36 state constitutions declare, in some form or other, that it is the right of the people to abolish or alter their government when they deem it necessary….some states go so far as to place a direct responsibility on the people to rid themselves of injustice….Today, with over 15 million unemployed, and a third of our population dependent upon them…our method of government is not providing security, nor does this government even see to it that at least no one starves to death for want of a job….”

Rieve was followed by John A. Simpson, president of the National Farmers Union:

“I want in the beginning to divide this country into two classes. In one group there are the 120 million common people whom I call the debtor class. They are worth all the way from nothing to a little less than nothing. In the other group are the 10 thousand ultra rich whom I call the creditor class. They are worth all the way from a few millions of dollars to a few billions of dollars. I am not making this division to create class hatred. I do not want you to hate an Andy Mellon, a Henry Ford, but I do want you to hate, with an undying hatred, a system that makes it possible for one man to accumulate two billion dollars of wealth in a lifetime….Let us go out from this convention fully determined to do everything possible to take control of this country of ours from the grasping, selfish hands of the 10 thousand ultra rich and place it in the hands of the 120 million common people.”

Next came Norman Thomas, who had just received 884,781 recorded votes —- and probably more actual votes — as the Socialist candidate for president a few months earlier in 1932.

Leaders of the Socialist Party and the heads of sympathizing union leaders, like Emil Rieve, played a dominant role in the Congress but the response to the call came from a far wider audience. The radical talk may seem odd today, but it was common coin in those desperate days of deep depression, mass unemployment, and suffering. As late as 1936, an impressive group of prominent intellectuals signed a statement endorsing Thomas for President, one that used some of that same language.

From Thomas’s opening speech, we read:

“There never has been a congress like this in Washington….We seek no impossible balance between exploiter and exploited, worker and shirker, master and slave. We have come in the spirit in which our ancestors built this nation to write a new Declaration of Independence against evil infinitely worse than they suffered at the hands of a British monarch, and to organize for the struggle from which we shall not rest until we have made that declaration effective for ourselves and our children…. Within a few weeks, we have seen Germany go the way of Italy or worse…..There is no magic in America or in us to prevent our drift to a similar Fascism….

“What shall we do in this crisis? That is for this conference to decide, not for this speaker to dictate. I do not assume that there is complete agreement among us…. Yet, we shall fail unless we recognize that there can be no rest in our crusade short of a federation of cooperative commonwealths of mankind….”

U.S. Senator Lynn J Frazier of North Dakota followed to say that

“The capitalistic system with its selfish greed for financial gain has resulted in the massing of enormous wealth which has been concentrated into fewer and fewer hands…. That system has been the cause of bankrupting the nation…. There must be a change. Capitalistic control must be broken. Excess profits and the vast amassing of wealth must be controlled and can be by a proper system of taxation.”

When it was announced that the Cairo Hotel discriminated against colored delegates, A. Philip Randolph, for the conference, organized a withdrawal of all delegates from the hotel and a mass protest demonstration on the outside.

Sunday, May 7, 1933, the second of the two-day assemblage, received committee reports, adopted resolutions, established a continuing national organization, and laid plans for the coming battles. The tenor of the times, already reflected in the opening addresses, was repeated in resolutions reported out by the committees and adopted by the delegates. Among them:

- Increased taxation on the wealthy, all income over $25,000 a year to “be recaptured by the government,” a capital levy on wealth.

- Government takeover of banks “to finance farmers and small homeowners instead of stock exchange gamblers and gamblers in commodities.”

- Cooperation “with militant farmers now subject to martial law by offering them legal and financial aid.”

Later, A.C.Townley, representative of the Farm Holiday movement, spoke of farmers on “strike,”— they would be dumping milk on the road —. Delegates responded with a six-minute ovation when he said,

“…We fight not against starving unemployed but against this gambler’s system of distribution which takes away their jobs no matter how much they produce…. You can strike, too, you can enter into a league with the farmers so you can eat while you strike….”

In the anti-war mood of the times, the convention repudiated the “tyranny of the U.S. Marines and the harsher tyranny of U.S. financiers and industrialists.” It denounced imperialism and arms production.

Among other resolutions proposed by committee and adopted by the delegates:

- For civil liberties, the end of restrictions on immigration, for justice to the Scottsboro boys, for equal rights for Negroes.

- A resolution calling for the recognition of the Soviet Union and hailing it as a socialist government was rejected 900 to 734 but a simple resolution for recognition, but without implying praise of its regime, was adopted.

- A resolution for the formation of a new “united political party” was rejected on the ambiguous ground that the Congress had been convened to formulate an economic program not to consider forming a political party. But an ambitious plan was adopted for the formation of “a permanent national organization to be known as the Continental Congress of Farmer and Workers…. to fulfill the plans here adopted, including the exploration of the best methods of economic and independent political action by the producing classes for the achievement of the cooperative commonwealth.”

- A national committee of 26 was established, representative of all the participating organizations. Unions, political groups, and farmers’ organizations were each assigned five members. Conveners were appointed for 40 states and the District of Columbia to set up a system of state and local organizations to “stimulate and coordinate united mass action for the aims of the Congress,” in particular for: demonstrations for “the aims of the Congress”; relief to the unemployed; support to “workers in industrial struggles”; against evictions; support to farmers “against speculators, bankers, mortgage holders, unfair taxation.” The affiliated sections were to develop a labor culture program of study groups, sports groups, singing societies, women and children clubs, art and dramatic groups. They would each form a youth section.

It was an ambitious program, in many ways an impossible program, born out of desperation, hope and enthusiasm. But they seemed determined to make the try. In hindsight, for us today, their aspirations may seem like the imaginative creation of radical, utopian dreamers. But the key initiators and participants were no eccentrics. Many were socialists, yes; but down to earth and practical. Among them, Darlington Hoopes, David Saposs, Dan Hoan, Katherine Pollak, Julius Gerber, Powers Hapgood, Jasper McLevy, Sidney Hillman, A. Philip Randolph, Henry Linville, James H. Maurer, David Dubinski, Leo Krzycki, Clinton Golden, Robert Morss Lovett, Emil Rieve, James O’Neal, Paul Blanshard, Harry Laidler, Edward Levinson, Jacob Panken, B.C Vladeck, Louis Waldman, and of course the avatar of practical idealism, Norman Thomas.

Over 200 union officers, community leaders, farmers’ representatives and others from 35 states had signed the Continental Congress call. In response, 4,390 delegates registered, representing the following organizations:

Political 1,497

Coop and educational 442

Farmers 193

Unions 535

Student and youth 401

Unemployed 742

Labor fraternal 580

They left Washington inspired and keyed for major battle.. And yet, within a few months, it was all gone and soon forgotten. In those few months, the movement was bypassed and co-opted by Roosevelt and the New Deal.

Looking back, a passing hint of what was to come can be detected in Norman Thomas’s opening address: “There are things that have been done in Washington in these last crowded weeks of which most of us would approve.” FDR had been elected in November but didn’t take office until March, just two months before the conference opened, and no one knew how he would go, no one could anticipate the explosive New Deal.

Of course, the New Deal could never satisfy the socialist aspirations of Norman Thomas. At the Congress, a resolution, brief and to the point, called for the “public ownership and operation” of all the main industries administered by boards of directors on which workers, consumers, and technicians were fully represented.” It was apparently adopted routinely without debate. Such was the mood of these delegates. At that moment, everyone was happy to bash the capitalist system

But the report of the committee on Unemployment and Economic Insecurity and the resolution adopted by the delegates went on at length. In detail, and down to earth, it spelled out what they demanded:

Three billion in cash relief

Bonus to unemployed veterans

Five-day week, six-hour day without pay reduction

Six billion in public works

Unemployment insurance, old age insurance, sickness insurance

Abolition of child labor

Reduction in interest and principal on home mortgage

Government take over of banks

Inflation to begin by inflating wages

Roosevelt’s New Deal soon convinced them that the country was going their way. It offered enough to convince them that they might satisfy their most pressing needs by working with the new regime, not against it. It offered enough to wean the unions and their leaders away from the diehards of the Socialist Party. And so the burgeoning movement, with all its radical implications, disappeared into the New Deal. Nevertheless, in those two 1933 days in Washington, the Continental Congress of Workers and Farmers demonstrated that, at that moment, those who sought social justice in this country were poised to take a new political road.

Leave a Reply