Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film “The Master,” starring Joaquin Phoenix, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, and Laura Dern, might alternatively have been titled “Masters and Followers,” for the movie is as much about his followers as it is about the character of the master, Lancaster Dodd (played by Hoffman).

The film is an exploration of what the philosopher G.W.F. Hegel called “the master-slave dialectic,” the relationship between the powerful and the powerless, between dominance and dependence. According to Rotten Tomatoes critics love this film (85%), general audiences not so much (63%), no doubt in part because the film's loose plot and unfulfilling conclusion fail to provide an adequate structure for the strong acting and brilliant cinematography. Anderson asks us to contemplate the patriarch-tribe, father-son, teacher-student, master-servant relationships, but also to ask whether or not in such a world as ours any sort of healthy, free and autonomous existence is possible, and what that would look like. The film’s attraction is its intellectual and moral challenge: can we live without masters?

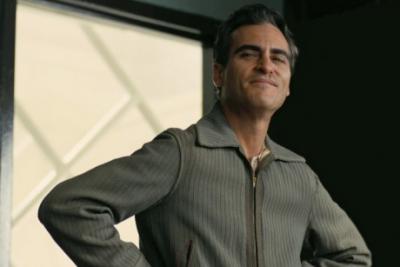

Freddie Quell (intensely portrayed by Joaquin Phoenix), a shell-shocked, broken-hearted, alcoholic, World War II Navy veteran and seaman, who in his post-traumatic state finds it hard to hold a job or establish a relationship with a woman, fleeing his accidental killing of a coworker, stows away on a ship that turns out to belong to Lancaster Dodd, the leader of a spiritual movement called The Cause. Dodd takes an immediate interest in Quell and through an intense psychoanalytic, confessional “processing” session leads his subject to face the fact of his broken heart. Master and servant bond, and even if the tie is not permanent—for Quell is one of those who would be free—the Master is powerful and for a while overpowering. (Trailer.)

The Master and the Cause

Through the eyes of Quell, and the fabulous cinematography of Mihai Malaimare Jr., we learn about Dodd and the Cause, a transparent fictionalization of L. Ron Hubbard and Scientology, with the same mix of science and spiritualism, hypnotism and reincarnation, healing community and outright cult. When he first meets Dodd, Quell asks what he does, to which Dodd replies, “I do many, many things. I am a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a theoretical philosopher.” Dodd’s Cause, combining Christian perfectionism, Freudian psychoanalysis, spiritualism, and pseudo-science—just like Hubbard’s Scientology—proselytizes through a process of personal manipulation and intense brain-washing. (See here for a documentary with an interview of L. Ron Hubbard.)

Hoffman as Dodd is appropriately magisterial, paternal, and pompous, while at the same time garrulous, intimate and sentimental, never a tyrant but rather the all-wise, all-powerful father beaming down on his tribe. Paul Thomas Anderson understands that the master of a cult is never simply a charlatan, but always as much self-deceived as he is deceptive, as monomaniacal as he is manipulative. In this case Hoffman’s young wife Peggy (Amy Adams)—a character in the story which apparently has no parallel in the life of L. Ron Hubbard—is the one person not under his control. She is his more opportunistic partner, the organizer of his household and entourage, and at times the driving force in his latest project.

The Nature of the Cult

Set in the immediate post-war period, the film is also an examination of what author David Riesman, a sociologist of that era called The Lonely Crowd (1950) of modern American life with its “other-directed individuals” looking for meaning and direction usually from corporate advertising and their suburban neighbors. Those unsatisfied by the subdivisions and consumerism—the displaced and disoriented—sought direction and solace elsewhere. Dodd and the Cause, as suggested by the case of Quell, provide spiritual guidance and do social work for the lost, the broken, and the sick, while for the wealthy and well-off they provide meaning to those whose lives seem meaningless. Throughout the film as Dodd wanders from San Francisco to New York to Philadelphia, staying in the homes of the well-to-do, he conducts séances, gives lectures, and in general inspires his well off followers. In New York City, however, an argument with a critic and an altercation involving Quell lead to buyers’ remorse and Dodd is arrested and sued for bilking a foundation and practicing medicine without a license.

All of this, of course, is in the nature of the cult: the enlightened guru, the inner circle of the cognoscenti, the mystical knowledge, the community of believers, good works or social welfare, the militant defenders of the faith, but also the financial shenanigans, the trouble with the law, the inevitable persecution and flight. And sometimes too there are martyrs. The cult speaks to those societies disrupted by modernization, to those individuals whose personal lives have been ruined by abuse, violence, divorce, untimely death, unemployment and eviction, or because they make up the downtrodden and the down-on-their-luck. The guru provides clarity to the confused, answers to the questioners, a destination to the seekers, and perhaps most important a community to the lonely, the alienated, and the desolate. In a world that for many is a spiritual vacuum, the guru and his cult provide a surfeit of the spirit. Dodd/Hoffman is the friendly face of the guru, the father, the guide.

All of this is so familiar to us in the more usual religious way. We could be talking here about Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormons, Jim Jones of the Peoples Temple, Jim and Tammy Faye Baker of the Praise the Lord (PLT) Club, or anyone of dozens of Evangelical mega-church or television preachers. What’s different about Scientology or the Cause is the attempt to modernize the ancient spiritualism by combining it in some way with science or at least the aura of the scientific. We saw this at the beginning of the twentieth century when a split occurred in Madame Blavatsky’s purely spiritual Theosophist movement and Rudolf Steiner left to found the Anthroposophy movement, claiming to combine the spiritual and the scientific. Steiner too was a philosopher, scientist, and spiritual leader who blended Eastern religion and Christianity, subscribed to a kind of communitarianism, believed in reincarnation and called his Anthroposophy “the spiritual science.”

It was the tendency of American Protestant Christianity of the Evangelical variety, and particularly the perfectionist strain within it, that led sociologist Howard P. Becker to coin the term “cult” in 1932. The cults Becker studied were the small churches constantly spun off from more mainstream Protestant faiths, resulting in myriad micro-sects each with its own unique theology. Led by charismatic preachers with mystical beliefs who created new variations of old rituals and practices, they proliferated throughout the American Bible Belt of the Lower Midwest and the South. Some of these Protestant preachers were simply hucksters retailing religion while others were conmen bilking the gullible and sometimes seducing the innocent. Fascination with that sort of cult led to Sinclair Lewis’ wonderful 1927 novel Elmer Gantry and the movie adaptation by the same title starring Burt Lancaster. Gantry portrayed by Lancaster says in the trailer, “Elmer Gantry is an all American boy. He’s interested in money, sex—and religion.” (See 1960 trailer.) We recognize that Gantry is kith if not kin of Dodd.

While it is usually religion that spins off sects and cults as easily as the winds blow up dust devils on the prairies, politics can do so as well. Politics too has its cults. L. Ron Hubbard, who wanted one day to have his own kingdom, bears a striking resemblance to Lyndon LaRouche, the neo-fascist guru who also claims to know it all, from politics to economics to musical theory. While LaRouche represents the political cult on the far right, we also have Bob Avakian, perpetual chairman of the Maoist Revolutionary Communist Party on the far left, the developer of what he calls a “New Theoretical Synthesis.” He takes pride in the cult of personality he has created around himself through the program actually called “Appreciation, Promotion and Popularization of Bob Avakian.”

Sometimes the cult becomes transformed into more significant populist politics, as in the case of Huey Long, known as the Kingfish, the populist governor of and then senator from Louisiana. The master not as leader of a sect but as head of a political movement. Here we have the Evangelical preacher as radical demagogue and the search for meaning, security and community transformed into a political party organized around a personality. Robert Penn Warren’s powerful Pulitzer Prize-winning novel All the Kings’ Men, a fictionalization of Long’s career, was later made into a movie in 2006 starring Sean Penn as Willie Stark, the fictional Long. We see in this film another master who tells a younger man who works for him: “Boy, you work for me because I’m the way I am, and you’re the way you are, and that’s just an arrangement in the natural order of things.” (Trailer of All the Kings’ Men.)

Toward the end of “The Master,” Quell has decided to leave The Cause and Dodd says to Quell, “Well, see if you can live without a master, for if you can, you will be the first human being in all of history to do so.” Dodd’s suggestion that we all live with masters is the film’s great question and challenge. Liberals and conservatives in our society claim to value the individual and his or her rights above all, yet we live in a society where for most the development of their individual abilities and personal fulfillment are not possible. The anarchists say “No God, No Master,” (“Master” in this case meaning boss) and “No Church, No State,” slogans that raise the idea of personal autonomy within the community of producers. Socialists envision a society organized around the idea that a society of abundance, collective ownership and democracy would allow the development and fulfillment of the individual. Yet socialist revolution has ended in the past in authoritarian states. The society without masters or servants remains a dream.

Leave a Reply