Labor is prior to, and independent of, capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital and deserves much the higher consideration. – Abraham Lincoln

Labor is prior to, and independent of, capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital and deserves much the higher consideration. – Abraham Lincoln

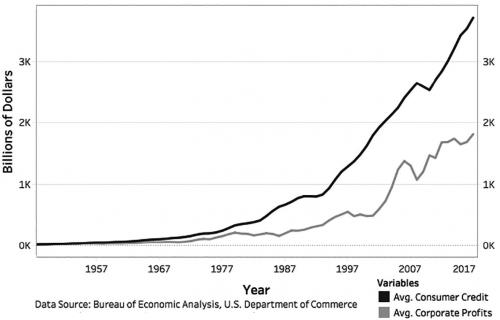

It was recently uncovered that Amazon, like many other corporate giants, effectively paid $0 in federal taxes in 2017.1 The new federal tax bill and the retrenchment of the state during one of the most profitable eras in recent history is alarming. Since 2008, corporate profits across many industries have increased exponentially; yet income gains for the working class have remained sluggish. Profitability doesn’t necessarily entail equitability—although it could. The present scenario of increasing profits paired with relatively small income gains for the working class creates conditions ripe for overproduction and underconsumption. Consumption since 2008 has largely been fueled by cheap money (low interest rates) and increasing private household debt. How else can the economy grow if workers aren’t making any more money to fuel their consumption?

Corporations are not beneficent creatures; they are vehicles that largely absolve any particular individual, or group of individuals, of liability as they pursue capitalism’s instrumental rationality: capital accumulation for its own sake. Alternatively, surplus value, or profits, can only be produced by labor and is extracted by capitalists by paying workers a wage that is equal to less than what they produce for that corporation. Even more confounding for the labor movement is that workers themselves and the products they produce are highly diverse; the rate of return is highly differentiated between skilled and unskilled workers and is determined, partially, by class, race, gender, geography, and the political structures within which workers and corporations operate.

Thus workers, nationally and globally, are fractionalized, which makes solidarity and organizing difficult. What is also damning about this neoliberal capitalist order is that material necessities, like nutritious food, clean water, clean air, and housing, are not presupposed. There’s no minimum wage in any state in the United States that, by itself, can pay for these necessities. Thus many in the working class are forced to work multiple jobs just to maintain themselves.

This is particularly true for Seattle’s working class. The median home price has just surpassed $700,000;2 that’s double what it was some five years ago. And the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment is over $1,700 a month.3 Even if someone is making Seattle’s comparatively “high” minimum wage, paying just for rent requires more than 120 hours of work a month. That is equivalent to three weeks of full-time work, before putting bread on the table. As median housing prices and rents go, Seattle is at the high end nationally.

While our intent is to focus on relieving the stress on the working class, part of that process is recognizing the brewing perfect storm caused partially by Seattle’s geography and changing demographics. Unlike many other cities, Seattle is geographically constrained by the Puget Sound to the west and Lake Washington to the east. Microsoft, which is headquartered in Redmond, Washington, has already priced most of the working class out of the eastern portion of the metropolitan area. While many cities can expand and develop in all directions, Seattle can’t. Seattle’s working-class population has two options: either move farther north or south of the city, or compete for a largely inelastic supply of housing within the city proper. Because Seattle has limited development options, the city and state need to take on a more activist role in fostering and structuring housing development and strengthening regional transportation—which has largely been absent in the last two decades—if the working class is to have a chance at affording the cost of living.

Seattle is no stranger to the growth effects of tech companies. At times in the 1960s, nearly one in four employees in the city worked for another tech giant thought to be on the cutting edge of the economy, the Boeing Company. The lessons from that experience are instructive, particularly in what city residents must do to protect themselves from the boom and bust swings of big business.

To say the company-town experience did not go too well back then is an understatement. In 1969, Boeing’s business forecasts failed spectacularly. Its investments and hiring fell out of sync with its commercial airline sales. Federal contracts, the company’s savior in the past, were in short supply. The result was near-bankruptcy and the elimination of 60,000 jobs, sparking what locals remember today as the “Boeing Bust”: an unemployment rate peaking in 1971 at 15 percent and the starkest and most sudden economic urban crisis in the United States since the Great Depression.

Seattle’s economy ultimately stabilized. How it did so is not well understood. The Bust is often summoned as an unfortunate but necessary prelude to the prosperity of the Microsoft-driven development of the 1980s—unfortunate due to its severity, but necessary to diversify Seattle’s economy and reduce its dependence on Boeing. But this imagines a magic thread from Boeing to Microsoft that simply does not exist. It took the city another decade to overcome unemployment rates higher than the national average, with the area’s continued dependence on Boeing heightening the severity of the Reagan-era recessions.

More significantly, accounts of the Bust overlook the economic protections—especially those traceable to organized labor—that prevented the urban economy from imploding entirely. In 1973, the RAND Corporation partnered with researchers at the University of Washington to study why Seattle’s economic crisis had not hit harder than it did, with consumer spending remaining steady throughout the crisis. Nearly every reason cited by the study, from the high wages of residents to the relatively short unemployment periods of laid-off aerospace workers, could be traced to unions at Boeing, namely the International Association of Machinists District Lodge 751 (one of the largest unions in the country prior to the Bust) and the Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace.4

Washington state has always been a leader in union membership rates when compared to the rest of the nation; many of these workers are government employees. Union membership rates in the mid-1960s stood at 44.5 percent, whereas today, only 16.8 percent of workers are in a union. It is no surprise why today’s Seattle is very different than it was forty years ago. The Seattle area has been growing its professional class—workers employed at Amazon, Starbucks, Microsoft, and Google comprise an increasing number of highly paid professional workers who are not unionized. Unlike unionized employees, these nonunionized private-sector workers have access to fluid financial capital, which gives them a competitive advantage over working-class individuals with access to little or no capital. In a housing market with short supply and high demand, capital wins every time.

Rents and housing are suffocatingly expensive and punish those who are not caught up in the industries that are growing Seattle. If Seattle wants to maintain its reputation as a progressive bastion in the West, then it must do more to insulate its working class from the inflationary effects of the incoming professional class. Housing is, at its core, a political issue, as David Madden and Peter Marcuse have recently argued: “The residential is political—which is to say that the shape of the housing system is always the outcome of struggles between different groups and classes.”5 Indeed, Seattle has been growing in a particular way. What was once a working-class city with high union membership is now becoming more professional and nonunionized. This divergence between the working and professional classes makes Seattle one of the more predictive labor battlegrounds in the nation, pitting the working class against a growing professional class. This clash of classes also presents the city with a great opportunity, we argue: the chance to reform housing and form the foundation for a more equitable and progressive city. After all, in an ever-changing technology landscape, who is to say that Amazon will not follow Boeing’s footsteps?

The Washington state government has been disturbingly absent when it comes to the plight of the working class. The state routinely cites its lack of tax income available to fund basic K-12 education, affordable housing, and public transit; yet, the state is also one of the richest and most prosperous in the nation. Washington is one of only seven states in the union that doesn’t tax income. According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, the state of Washington has the most regressive tax system in the nation, penalizing the working poor while creating an underfunded, and thus, unresponsive, state government. We argue that it is vital for the state to institute a progressive income tax to account for Washington’s shifting demographics. Forgoing an income tax in favor of a sales tax will forever leave the working class worse off. Taxing consumption, not income, means that the state’s growing professional class is left with a larger share of income not taxed by the state. This potential revenue could be used to reduce or eliminate the shortage of tax dollars available to fund K-12 education, while also financing an affordable housing program that insulates the working class from rising costs of living.

Second, we believe that removing the state ban on rent control could benefit the working poor. The state banned rent-control measures in 1981, and legislators have never realistically revisited the potential benefits of rent control until recently, with the introduction of HB 2583. Low- and moderate-income workers provide essential services to cities and the state, and when they are priced out of large metropolitan cities, they disproportionately bear the costs of growth. What’s more, rent control has the potential to increase neighborhood diversity and stability, thereby mitigating the gentrifying effects of the rapid demographic changes detailed above. There are many opponents to rent control, but if quality of life is a political concern, then there are simply things that can’t be left up to the market and, in turn, need some government intervention—otherwise, we might all be living in micro-apartments that are smaller than 350 square feet.

Lastly, a concentrated effort to revitalize the strength of democratic labor unions in the state of Washington and the nation is central to the future success of the working class. Historically, labor unions in the state have protected workers when the inevitable busts to the booms of the business cycle rear their ugly heads. Recent events in West Virginia and Oklahoma prove that unions are vital to fighting the power of capital. Only together can we stand up and face the interests that hope to undercut our livelihoods for the sake of profits. Since the election of Donald Trump, the unionization rate in the state of Washington has climbed to 18.8 percent,6 making Washington the third most unionized state in the nation. Continuing this trend, while also building cross-industry solidarity, is necessary to account for the highly differentiated labor that makes cities and states prosper.

These are but a few recommendations that we hope can temporarily alleviate the strain on the working class. Corporations are currently raking in record profits while working-class wages have remained stagnant. The rapid increase in the cost of living and private household debt are creating a perfect storm just waiting to further discipline the working class. We should learn from Seattle’s history; corporations think workers are disposable commodities that can be ditched at a moment’s notice. It’s up to the workers themselves to insulate each other from the perverse interests of capital.

Footnotes

1. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, "Amazon Inc. Paid Zero in Federal Taxes in 2017, Gets $789 Million Windfall From New tax Law", February 13, 2018.

2. Seattle Times, "As Seattle Home Prices Soar Some Would-Be Buyers Now Giving Up", October 5, 2017.

3. Seattle Times, "Rent Hikes Slow Around the Country but Surge Again in Seattle. What's Going On?", June 27, 2017.

4. A sincere thank you is owed to Andrew Hedden for providing this rich labor history of the Seattle area.

5. Jacobin, "The Permanent Crisis of Housing", October 2, 2016.

6. The Stand, "Washington State Posts Big Gians in Union Memebership", January 22, 2018.

Leave a Reply