On March 19th, 2018, Gov. Phil Bryant of Mississippi signed into law the earliest abortion ban in the United States, restricting abortions after 15 weeks in the entire state. The day after, the Supreme Court housed debate on the legality of a California law regulating speech at anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centers, which required that they present information about affordable abortion, contraception, and prenatal care, and to display signs saying that they are not a licensed medical clinic, in cases where they are not. This has re-ignited debate over the appropriate stance for the left to take on abortion, and whether there is space on the left for anti-abortion views.

On March 19th, 2018, Gov. Phil Bryant of Mississippi signed into law the earliest abortion ban in the United States, restricting abortions after 15 weeks in the entire state. The day after, the Supreme Court housed debate on the legality of a California law regulating speech at anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centers, which required that they present information about affordable abortion, contraception, and prenatal care, and to display signs saying that they are not a licensed medical clinic, in cases where they are not. This has re-ignited debate over the appropriate stance for the left to take on abortion, and whether there is space on the left for anti-abortion views.

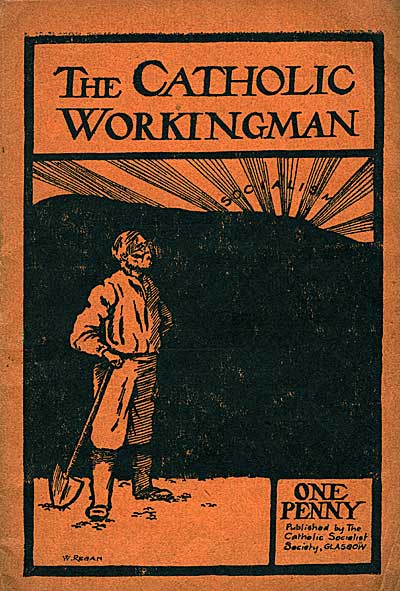

As part of this discussion, a 2014 article by Elizabeth Bruenig (née Stoker), in which she lays out her belief system as a “pro-life leftist”, has resurfaced and sparked much debate on Twitter and elsewhere. While she has since expressed opposition to abortion criminalization, in this article Bruenig (who is Catholic) explains how abortion is “contrary to Christian ethics,” and should therefore be discouraged through social democratic measures aimed at reducing its necessity, such as universal healthcare, paid parental leave, and a state-supported child allowance. Bruenig presents this stance as bridging the divide between socialism and Christianity; however, her top-down approach to Christian socialism reflects a fundamental error about the role of religion in the lives of most believers, and ignores the rich history of Christian socialism-from-below, in which working class experiences and needs have been prioritized over the standards of church elites.

The phrase socialism-from-above refers to a 1966 pamphlet by Hal Draper called “The Two Souls of Socialism,” in which he proposes a fundamental division between those who would seek to institute socialism at the hands of an elite minority (“socialism-from-above”), and those who promote a socialism by and for the proletarian masses (“socialism-from-below”). According to Draper, the defining characteristic of socialism-from-above is “the conception that socialism (or a reasonable facsimile thereof) must be handed down to the grateful masses in one form or another, by a ruling elite which is not subject to their control.” In Christian socialism, socialist theory is fundamentally linked with Christian morality; as such, if church hierarchies are allowed to determine all aspects of Christian socialist morals, the socialism in question will at least partially be determined by the rule of church authorities. In “Why I’m a Pro-life Liberal,” Breunig assumes that the morality of the Catholic church with regard to abortion represents the totality of Christian ethics, and that Christian socialism must follow by promoting measures to reduce the occurrence of abortion. In reality, however, the stances which Christians take on abortion are anything but homogenous, and do not neatly reflect the positions of church institutions.

Polling results on religious attitudes on abortions vary widely, and survey questions have largely focused on whether it should be legal, rather than more abstract questions of its morality. However, a 2011 survey by the National Catholic Reporter found that 52% of Catholics believe that the authority to determine the morality of abortion lies with individuals, not with church leaders. Similarly, according to a 2017 Gallup poll, approximately 50% of mainline Protestants (ranging from 57-46%, depending on denomination) consider abortion to be morally acceptable. These numbers are significantly lower for evangelical Protestants, but still, from 13-27% of Baptists, Non-denominational Christians, and Pentecostals consider abortion to be morally acceptable. So even for evangelicals—who make up a minority of Christians in the U.S, albeit a vocal one—opposition to abortion is hardly unilateral. Among these three divisions of Christians (Catholics, mainline Protestants, and evangelicals), only in mainline Protestantism do official church statements condone abortion. However, few Christians in practice view church doctrine as a rulebook which must be followed exactly; as such, we regularly see disagreement from lay Christians even on subjects on which church authorities have clearly delineated positions. As such, actual Christian morality generally comes “from below” even for Christians without any socialist politics, and even in the Catholic Church, where official interpretations of the bible are meant to be determined by the Vatican rather than by individual Catholics.

So if the ecumenical of U.S. Christianity, and of the Catholic Church specifically, is not wholly pro-life, why does Bruenig act as though Christian socialists must oppose abortion? Even the Catholic socialist tradition specifically, by and large, has not represented rigid adherence to canon law. The Brazilian theologian and former priest Leonardo Boff, an early proponent of liberation theology, was censured by the Church in 1985 for his book “Church, Charism, and Power”, which critiqued the church for its hierarchies, involvement in human rights violations in Latin America, and participation in class society. Don Primo Mazzolari, the Italian priest and anti-fascist partisan who preached about a “church for the poor” was suspended from preaching outside of his diocese, and had a magazine he founded cancelled by the Vatican. And Catholic Worker, the paper of Dorothy Day, perhaps the most widely known Catholic socialist, dropped from 150,000 to 30,000 subscriptions when she went against the church hierarchy by refusing to support Franco over the (largely anarchist and communist) Republican forces. The most important task for socialists, Christian or otherwise, is to be on the right side of history. And while in many of these cases the Church eventually came around—Pope Francis recently made a pilgrimage to honor Mazzolari, and Day is currently a candidate for canonization—these examples illuminate a Christian socialist morality stemming not from the Vatican, but from everyday priests and lay people.

Even among non-socialists, lay Catholics and clergy alike regularly rebel against social teachings that limit bodily autonomy in order to police social reproduction. According to a 2010 survey by the Guttmacher Institute, Catholics get abortions at about the same rate as the general population. While the Catholic Church’s official stance on homosexuality promotes celibacy in order to avoid sin, a “GLBT Ministry” of Franciscan priests in New York provides an affirming and inclusive space for queer Catholics. And in 2014, the National Coalition of American Nuns took a stance against the Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision, which allowed for employers to make decisions about employees’ access to birth control. Bruenig’s doctrinaire theologism attempts to “bridge the gap” with an imaginary Christian sector of the working class which is far to the right of most actual Christians.

This misconception of working-class Christians is important, as it cuts to the core of a form of socialism-from-above that has recently become common within the social democratic milieu. In this form, the working class is assumed to be unilaterally reactionary and opposed to anti-oppression politics; as such, attempts to appeal to the working class end up embracing reactionary politics. Bruenig isn’t wrong to note that the majority of the U.S. working class is Christian, but her mistake lies in assuming that the best or only way to appeal to them is by abandoning core socialist principles. In reality, Christians are already working on some of the same issues as socialists; for instance, churches across the country have begun offering sanctuary to immigrants facing deportation, as ICE is less likely to perform arrests in “sensitive locations” such as places of worship. Politics aren’t formed in a vacuum, or through sharing the right thinkpiece, but through practice, in coalition with others. It makes sense to prioritize working with Christian comrades on the issues on which we agree, rather than attempting to win them over ideologically by sacrificing our own principles.

Abortion is not a side project distracting from the “economic issues” on which socialists must focus; rather, the fight for reproductive freedom, including abortion rights, is an integral part of the class struggle. When abortion is discussed as a class issue, it’s often framed either in the terms of the economic factors which contribute to abortion’s necessity or in terms of the economic factors which restrict abortion access. Bruenig discusses the ways in which the need for abortion is often a matter of economic necessity, as justification for the social democratic measures which she proposes to reduce the need. Meanwhile, pro-choice leftists explain how abortion access is often limited by economic factors, and by policies such as the Hyde Amendment, which makes it so that state funding in the U.S. cannot be used to pay for abortions. But abortion access is an economic issue at an even more basic level, insofar as pregnancy and childbirth are an essential part of the social reproduction of the workforce under capitalism.

First developed by Lise Vogel in Marxism and the Oppression of Women, social reproduction is the process by which the institution of the family reproduces the labor force, which in turn produces value. This idea is foundational for Marxist feminism because it explains how, even though reproductive labor does not directly produce value, it is an essential part of the capitalist economy. According to Tithi Bhattacharya:

“Labor power, in the main, is reproduced by three interconnected processes:

1. By activities that regenerate the worker outside the production process and allow her to return to it. These include, among a host of others, food, a bed to sleep in, but also care in psychical ways that keep a person whole.

2. By activities that maintain and regenerate non-workers outside the production process–i.e. those who are future or past workers, such as children, adults out of the workforce for whatever reason, be it old age, disability or unemployment.

3. By reproducing fresh workers, meaning childbirth.”

It is, of course, the final process of social reproduction which is most relevant to this discussion. Pregnancy and childbirth is an essential part of ensuring that the workforce continues on and is able to produce value another day. As such, the right to abortion is the right to withhold one’s labor. This is a priority for us as socialists; we must oppose coercion into labor, particularly by means of economic necessity and/or state oppression, but also by soft power and social or interpersonal pressure.

Breunig claims that her stance on abortion is left-wing insofar as it attempts to reduce abortion through social democratic means, rather than through criminalization. But by assuming that Christian socialism requires an acceptance of abortion as sinful, she contributes to stigma which ultimately makes abortion harder to access for those who need it. Ultimately, abortion is a medical procedure, and feminists believe that it should be treated like any other necessary medical procedure. Medical procedures are not usually fun—they are often stressful, even traumatic, and can sometimes be invasive. Insofar as abortion can be all those things, there is nothing inherently wrong with wanting to reduce the need for it, just as there is nothing wrong with wanting to reduce the needs of mastectomies through screening and prevention. In fact, Bruenig’s specific policy proposals are eminently reasonable, and her stated opposition to criminalization is of course appreciated. But in context, when pro-life leftists use their platforms to advocate for reducing abortions for moral reasons, it still contributes to a culture of stigma which ultimately makes it harder for people who need abortions to get them.

There is a reason why abortion is treated differently from mastectomies; this is because of the stigma and moralism associated with these procedures. On the level of base/superstructure, this stigma exists because to get an abortion is to refuse the duty to reproduce the workplace. But the superstructure can also have concrete impacts; while stigma is not a direct material determinant of abortion access in the way that anti-abortion policies or healthcare coverage are, it undeniably has an impact on both abortion access and the experiences of people who have abortions. For example, while parental consent laws have the most direct impact on minors’ access to abortion, it is stigma and moralism that makes it so they can’t ask their families for permission, financing, or a ride to the clinic. And even though Bruenig disapproves of some of the more extreme tactics of anti-abortion activists—finding them unsuitable to a “culture of life”—she nonetheless plays into the moralism about abortion which leads to the harassment of women at clinics, and to violence against abortion providers. This is particularly egregious because, as has been shown, pro-life politics are not a requirement for Catholicism or Christianity in general, and Christian socialists have consistently resisted church authority in circumstances where church policies went against socialist principles.

In developing a Christian socialism-from-below, then, it is important that we recognize the ideological diversity of the base of working-class Christians who make up this sector of the proletariat. While not all working class Christians are pro-choice, it makes no sense to reach out to those more conservative elements of the population at the expense of those working class Christians who have had or will have abortions. Ultimately, socialist politics cannot be proscribed an external authority, whether it’s a “vanguard” or the Vatican Council. Only through the united action of working class people of all religions, genders, and reproductive capabilities will we achieve proletarian liberation.

Leave a Reply