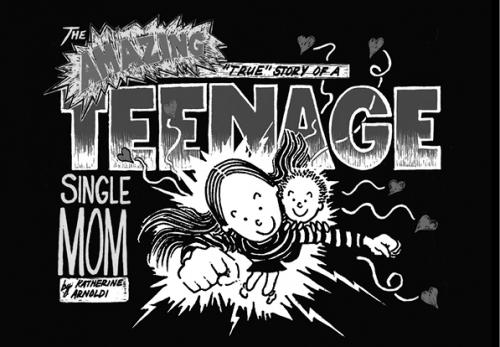

By: Katherine Arnoldi

Graymalkin Media, 2015, $12.99

By: Matthew Baigell

Syracuse University Press, 2017, $29.95

By: Paul Buhle and Noah Van Sciver

Fantagraphics, 2017, $19.95

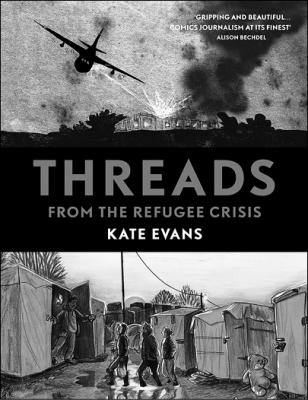

By: Kate Evans

Verso, 2017, $24.95

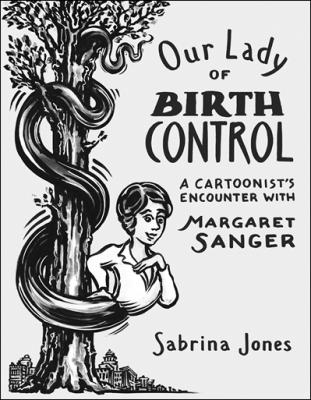

By: Sabrina Jones

Soft Skull Press, 2016, $19.95

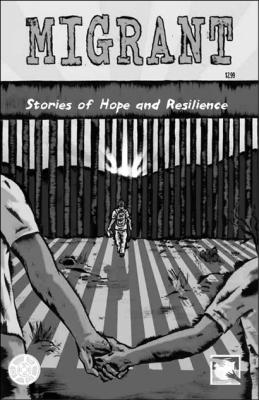

By: Jeffry Odell Korgen and Kevin Pyle

Hope Border Institute, 2017, $2.99

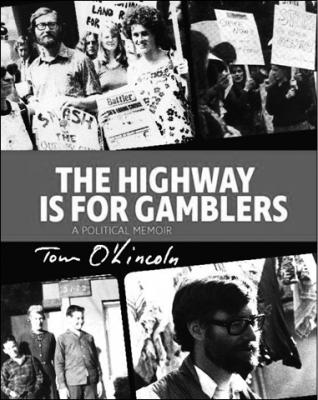

By: Tom O'Lincoln

Interventions, 2017, $30

By: Donald Rooum

PM Press, 2016, $14.95

By: James Walker and Paul Fillingham

Spokesman Books, 2016, $20

In her award-winning book Red Rosa (2015), Kate Evans combined feminist biography, intellectual history, and appealing visuals to tell the remarkable story of Rosa Luxemburg. While much of the narrative focused on friendships, relationships, and personal struggles, Evans also conveyed a sense of Luxemburg as a theorist of capitalism, imperialism, and war. In her latest work, Threads, Evans writes and draws about her experiences working alongside refugees in the so-called Calais Jungle, where thousands of people fleeing war, poverty, and political unrest in Africa and the Middle East converged in 2015-2016 in hopes of relocating to the U.K. She has once again crafted a powerful read.

Threads: From the Refugee Crisis is only one of many recently published works of graphic nonfiction, but it offers a persuasive case for comics journalism and comics memoir—categories or genres that barely existed before the present century. It helps that Evans has an eye for the telling detail and a knack for getting people to open up. At the same time, her pages place a greater emphasis on expressing raw emotion rather than on technical precision. As she records her experiences as a volunteer aid worker and part-time journalist, her personable approach to color, line, and page construction pays big dividends. She not only documents the logistical difficulties faced by the refugees, she registers the camp’s emotional temperature. I found myself gripped by Evans’ first-person encapsulations as well as by her secondhand renditions. By the end of the book, I was cheering her on as she calmly argues against austerity and “all national barriers to migration.” I also appreciated how her book offers a de facto rebuke to the anti-immigrant web posts she occasionally quotes in the text—“We need to purge this scum with fire there’s no other choice,” “these cute refugee babies grow into vile adults who want to destroy our country,” and so on.

Like Threads, the activist comic book Migrant: Stories of Hope and Resilience is grounded in interviews and in-depth reporting as well as secondhand sources. As part of their research, the authors spoke to “migrants, asylum-seekers, recent deportees and detainees, and Dreamers, men and women brought to the U.S. as children.” The comic book is bilingual; it was produced in partnership with Catholic groups in South Texas and northern Mexico that advocate for and shelter migrants and their families. While many of its pages are concerned with individual testimonies, others delve into larger issues of U.S.-Mexico relations and the push-pull of “economic forces at the border.” Jeffry Korgen and Kevin Pyle previously collaborated on Wage Theft (2013) and Worker Justice Illustrated (2014), and they have once again turned to the eye-catching comic-book format in order to call attention to the struggles—in both the positive and the negative senses of the term—of the most vulnerable sectors of the working class. Kevin Pyle also supplies the artwork, and his soft brushstrokes, indistinct linework, and off-kilter palette expose a world of exploitation that is granular in its specificity and yet familiar in its broad outline.

Another credible example of socially immersive cartooning is offered by Katherine Arnoldi’s The Amazing “True” Story of a Teenage Single Mom, which was first published at the end of the 1990s and recently reissued by Graymalkin Media. While Arnoldi’s book has largely been overlooked by the comics subculture, it has picked up awards from the New York Foundation for the Arts and the American Library Association. The book comes in the guise of a black-and-white paperback that resembles a comic strip collection rather than a full-color comic book or hardcover graphic memoir. As with Migrant and Threads, The Amazing “True” Story uses eccentric linework and unconventional layouts to pull readers closer to the extraordinary challenges faced by the main characters—in this case an indigent mom and her pint-sized daughter. Arnoldi’s lines are thicker and inkier than Evans’ and Pyle’s, and she sometimes steers the reader into trippy, underground comix territory in a way that seems out of step with the general drift of contemporary graphic nonfiction. The similarities between the three may be as significant as their differences, however, in that they each eschew the conventions of commercial narrative art, and they share a commitment to making politically charged comics about the freshly dispossessed.

Memoir and journalism are not the only approaches available to cartoonists pursuing nonfiction topics. Historical figures and episodes have also attracted attention from writer-illustrators. In Our Lady of Birth Control, Sabrina Jones brings a fluid, expressive, and sometimes minimalistic approach to the task of visually narrating key episodes in the life of pioneering feminist Margaret Sanger (1879-1966). While the book’s primary focus is on Sanger’s efforts to promote legal access to birth control, and her role in founding Planned Parenthood, Jones makes room for winsome autobiographical asides that highlight the extent to which past conflicts continue to reverberate in the present. Her “cartoonist’s encounter” with Margaret Sanger does not cover as much biographical territory as Peter Bagge’s Woman Rebel: The Margaret Sanger Story (2013), but her assessment of Sanger and the social movements she contributed to is far less guarded. Sabrina Jones’s other books include Isadora Duncan: A Graphic Biography (2008) and FDR and the New Deal for Beginners (2010), and she is a regular contributor to World War 3 Illustrated, a long-running journal of political cartooning.

Johnny Appleseed (1774-1845), born John Chapman, was just as real as Margaret Sanger, but he sometimes gets lumped in with frontier legends like Paul Bunyan and John Henry. As Paul Buhle notes in the introduction to his latest project, Johnny Appleseed: Green Spirit of the Frontier, Chapman “wandered perpetually, from his native Massachusetts to Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana.” He really did plant apple trees—tens of thousands of them—and referred to their seeds as “the seeds of love.” But the historical Johnny Appleseed was also an abolitionist, a vegetarian, and a women’s rights advocate, as well as a disciple of Emanuel Swedenborg, the eighteenth-century Swedish scientist and theologian. In recovering the life and times of this truly offbeat character, Buhle has joined forces with an up-and-coming artist, Noah Van Sciver. The results are impressive. Sciver has published short stories, mini comics, and comic-book anthologies, as well as a graphic biography, The Melancholic Young Lincoln (2012), but until now I had not thought of his work as having a political edge. His drawings have a rough-hewn quality that suits the material, and his craggy lines offer a nice fit with Buhle’s nomadic historiography. Sciver is good with street scenes and faces, but he really excels at depicting forests, farms, and animals—and toes and feet, for some reason.

The echoes of half-forgotten battles and movements can also be heard in the pages of Dawn of the Unread, a glossy anthology of graphic stories that celebrates the literary inheritance of Nottingham, England. The book “imagines a scenario whereby dead writers from Nottingham’s past are incensed at the closures of libraries and low literacy levels in twenty-first century Britain,” and return from the grave “in a loose twist on the zombie genre.” The featured writers include D.H. Lawrence, Alan Sillitoe, Geoffrey Trease, and Margaret Cavendish, a prolific seventeenth-century author whose “most famous work is The Blazing World (1666), a kind of utopian political thriller that’s credited as one of the first-ever science fiction stories.” Several of the stories in Dawn of the Unread are in black-and-white, and the artwork ranges widely in terms of style and tone. The book’s contributors seem to be mostly based in northern England, Wales, and Scotland and with a few exceptions—Eddie Campbell, Hunt Emerson, and Carol Swain—are unknown outside Britain. The book “originally started life as an online serial,” and in the course of developing the project, the editors organized “a very silent protest in the form of a reading flash mob.” Midcentury anti-comics campaigners used to complain that the ready availability of comic books would somehow threaten the survival of “real” books, but in this instance the medium has been mobilized on behalf of public libraries and the preservation of literary culture.

Donald Rooum has been drawing cartoons and comics for Peace News, Private Eye, and other U.K. outlets since the 1950s. His most successful comic strip, Wildcat, first appeared in the pages of the anarchist newspaper Freedom in 1980 and has been anthologized in a series of affordable pocket-sized volumes. Wildcat Anarchist Comics is the first collection of his work that is specifically aimed at a North American audience, and it will hopefully serve to introduce Rooum’s puckish cartooning to a new generation of readers. The book not only features numerous Wildcat strips, but also quite a few examples of Rooum’s work for The Skeptic. As Jay Kinney notes in his introduction, Donald Rooum’s

take on the anarchist movement is both didactic (his cartoons usually make a political point) and self-deprecating (he laughs at the foibles of his comrades and himself). These impulses are embodied in his two main characters: the professorial stork, a rather long-suffering anarchist ideologue; and “Wildcat,” a punkish anarchista much given to spontaneous outbursts and direct actions, many of them counter-productive.

Wildcat Anarchist Comics includes an autobiographical essay, and this is the first time that many of Rooum’s strips and cartoons have been published in color.

Political cartoons are not always on the side of the angels, of course. As Matthew Baigell demonstrates in his new scholarly monograph, The Implacable Urge to Defame, Jews were routinely and viciously caricatured in cartoons and illustrations in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century mass-circulation periodicals. Baigell reports that after looking through popular magazines like Puck, Life, Judge, and Judge’s Library, he “stopped counting anti-Jewish cartoons when the number went higher than one hundred.” The level of vilification of Jews was so “aggressive, debasing, and varied” that it shocked the author, even though he was already conscious of the extent to which, from the Middle Ages onwards, “images hostile to Jews have appeared in paintings, prints, cartoons, and sculpture in Europe and, in more recent times, in the United States and the Middle East.” One of the useful insights Baigell offers is that historians of newspapers, magazines, and print culture more generally have largely overlooked the issue of anti-Semitism. He also makes a solid case that anti-Jewish visual stereotypes were common in the Communist press of the 1920s and 1930s, especially in the years before the Popular Front. “Looking back at the Third Period,” Baigell writes, “it is difficult to parse precisely what was on the mind of many Jewish leftists when it came to Judaism.” Indeed, he suggests that the “Communist-controlled press” helped prolong “the use of stereotypical images of Jews into the 1930s.”

The title The Highway Is for Gamblers, by Tom O’Lincoln and edited by Janey Stone, is taken from a Bob Dylan song. O’Lincoln and Stone were active in student politics at Berkeley in the 1960s and relocated to Australia in 1971, where they became founding members of the country’s International Socialists. Tom O’Lincoln has always been a lucid and interesting writer, and over the years he has authored numerous articles and reviews for the IS press as well as several books and pamphlets on Australian history, including his critical survey of the Communist Party of Australia, Into the Mainstream (1985). Sadly, O’Lincoln was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease a few years ago, which is why Stone “stepped in to help produce this book, which has been drawn from a number of sources.” At the book’s core is an autobiographical essay that O’Lincoln wrote in 2015, but the volume draws extensively on “published articles, internal documents, letters, [and] unpublished draft essays,” as well as “memorabilia Tom kept from his travels, old diaries, letters and postcards to his family.” The Highway Is for Gamblers is stuffed with photos and images, including several hand-fashioned cartoons that satirize politicians and labor leaders. The Highway Is for Gamblers is not quite a graphic memoir but it contains a far greater range of visual information than almost any memoir of its type.

Leave a Reply