This year’s elections are the culmination of the long-standing economic and cultural grievances of America’s industrial workers, a subclass largely composed of white men from the Rust Belt whose factories have been asset-stripped and sent abroad and whose unions or small businesses, pensions, and prospects have been decimated. They are not the poorest of the poor—not even the poorest of the white poor. They are not from places where the economic conditions are the worst, but they are from places where uncertainty about the future of industrial jobs is most acute.

They are people who occupy a particular stratum within the economy. They draw their incomes from fashioning material commodities—from moving earth, by construction, through mining, and in manufacture—in contrast to the vast majority of workers now employed in the service sector, both private and public.

This was not, therefore, a revolt led by the white working class rank and file as it is currently composed, the many who never fully shared the benefits of life in the skilled trades and the once ascendant key industries of an economic power that had dominated the world by virtue of its industrial prowess. It was rather a revolt significantly fueled by those who had already acquired a quasi-leadership platform over the broad working class by virtue of the social weight that industrial employment had historically accorded them. For in their prime, it was industrial unions above all that had often fought for broad programs of social remediation and who spoke for the unorganized and unrepresented, albeit within the confines of an existing social order that they also jealously defended.

This election was a revolt headed, in part, by those who had acquired a modest stake in middle-class life and now find that life, and the institutions that made that life possible, disappearing. It is composed of white working men whose fortunes have fallen, afflicted by wage stagnation and an ever-widening social disparity in income and wealth that has consigned them to the wrong side of the divide. They prided and deluded themselves that they and they alone had reliably done society’s heavy lifting and were, in turn, entitled to certain expectations. Above all, they had the expectation of a well-run and stable social order, an order in which they would continue to enjoy a place of respect and authority with a rising standard of living, which could be passed down to their children, and a dignified retirement.

They had, above all, placed their confidence in the ruling class, who had historically indulged this self-estimation but then abandoned industrial workers in an increasingly globalizing economy. This sense of free-fall has been massively reinforced by a shift in equality’s center of gravity owing to greater racial and gender inclusiveness, with which it coincided. That abandonment has become a crucial factor in the increasingly polarized and caustic political conflict, a conflict that can be resolved in a progressive or reactionary direction, as the middle ground is quickly narrowing.

Rust Belt workers, or at least a strategic section, asserted themselves. But they did not assert themselves in a vacuum. Nowhere in the developed capitalist world has the left acquired traction. Our manifold debacles need not be rehearsed. Suffice it to say that the left has not provided an oppositional center of gravity that could capture this white working class disenchantment, engage with it, and transform that anxiety and outrage into a force for progressive change.

Few who urgently needed to extract actionable concessions from the system voted for the Greens. There are, of course, good reasons to cast a protest vote, to declare “no confidence” in capitalist parties, to put a place marker on a vision of liberation that may yet be. For many of us, the Greens unfurled the flag of independent political action and kept it aloft. But this is not the arena where concessions are realized absent a massive movement surge from below. Third parties don’t have to win elections to extract concessions, but they do need to attain a critical mass. And that mass, after a multiplicity of promising starts, has, unfortunately, failed to yet materialize and sustain itself.

When poor people and rank-and-file workers vote in the American system, they face a version of the “prisoner’s dilemma.” The best outcome relies on a very high degree of class and social solidarity. But if people fear that ranks will be broken, they build that anticipation into their calculation and opt for the least bad option. If poor people en masse had made the calculation that voting Green would get them closer to a $15 minimum wage or free college tuition, surely they would have voted on that basis. They understand that voting for the Democratic Party is a crapshoot and that the DP offers only the faint possibility of some piecemeal concessions. That, after all, is how the DP traditionally has kept its coalition intact.

But there was no evidence for a mass upsurge of working people breaking towards the Greens. And were it not for the Electoral College standing in the way of the popular vote, these Democratic voters might have made the correct calculation on the basis of their immediate short-term needs. To make this calculation in this way and to nevertheless vote Green, in defiance of that assessment, would have been a boutique option for many, if not most, hard-pressed people. This conclusion is frustrating and self-fulfilling. But it is not illogical.

The liberal wing of the American ruling class contributed to that calculation, having neutralized the Sanders insurgency and effectively corralled this discontent into the Trump alt-right pigsty, where, they thought, it could be contained. Clinton had something to offer Walmart and fast-food workers: a raise in the minimum wage, paid sick leave, subsidized child care, a modified Obama plan. She could offer a path to citizenship to the dreamers and subsidized public tuition. But having tried and failed to derail voter suppression throughout the South—and even in Wisconsin—and having manifestly failed to offer a grand, inclusive program of economic reconstruction to restore the white working class and sweep up the multiethnic poor and hard hit into a co-equal prosperity, Clinton could not counterbalance the appeal of the far right.

How could the party of fiscal prudence, the party that took great pride in “balancing the budget,” the party of free-trade enthusiasts, the party of neoliberalism, austerity, and diminished expectations, offer a compelling vision of a different future?

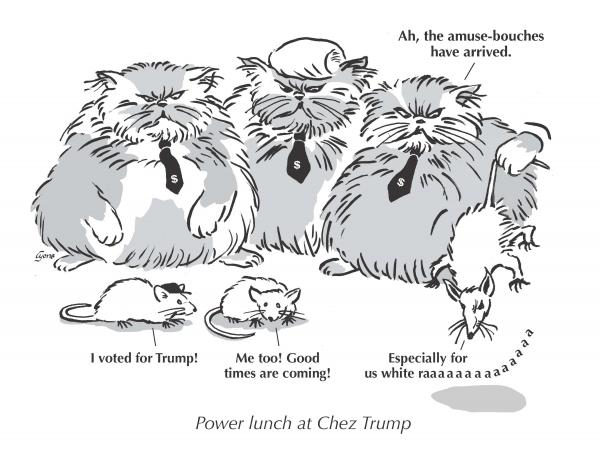

Clinton was perceived, and correctly so, as being the agent of global financial and corporate interests—a very specific Democratic “basket of deplorables”—that had inflicted this protracted social setback on white industrial workers.

She created the dilemma that came back to bite us all. She offered the Rust Belt a choice: Fight racism, misogyny, and xenophobia by standing with the Democratic coalition that offered them nothing; or stand with Trump’s white nationalists in opposition to social stagnation and decline.

This is an authoritarian moment and it is bleeding into advanced economies throughout the world, giving license and encouragement to a new, informal neofascist international. It was all but announced here by the open action of the deep state in the form of the FBI’s bombshell intervention on behalf of Trump barely two weeks before the election. And make no mistake about it: Neofascists, unlike traditional reactionaries and conservatives, are unencumbered by economic orthodoxies and can run an economy. They, like the far left, fully understand that capitalism is not self-correcting and place no faith in markets. They fully appreciate the need for massive doses of state intervention and are fully prepared to blow the deficit sky-high. And it will work, just as it has in the past. That is, it will work as long as the Trump nationalist coalition can thwart attempts by the Republican establishment to pay for this massive stimulus through offsets defunding social welfare programs that benefit Trump’s base.

That is why, contrary to Paul Krugman’s first instincts, the stock market, after an initial futures selloff, began to boom. Massive tax cuts, a protective wall of tariffs (seen less as a prescription than as a bargaining chip to renegotiate more favorable trade agreements), relaxation and elimination of environmental and Wall Street regulations, huge public works in the forms of infrastructural renovation, the promise of a border wall, and the spend-up on military hardware all herald and shape the state-led investment boom to come. Caterpillar and Martin Marietta stock prices soared. So did those of Big Pharma, soon free to price gouge without fear of criminal investigation. Raytheon, Northrup Grumman, General Dynamics, and Lockheed Martin had field days. Private prison corporations are licking their chops at the prospect of the FBI, ICE, and police being let loose on immigrant communities and communities of color. Student loan services and lenders, no longer facing government competition, got a new lease on life. Even too-big-to-fail banks’ stocks rose with the prospect of Dodd-Frank being repealed. Increasing after-tax incomes will stimulate working-class demand and, in the hands of the wealthy, drive up share prices.

Paradoxically, gun manufacturers saw a drop in stock prices. Speculators shorted gun stocks presumably because the threat of gun regulation has been removed, thereby eliminating the perceived urgency on the part of gun enthusiasts to stockpile arms in anticipation of that threat.

The Trump insurrection, assisted by this heartland revolt, effectively defeated the two political parties, the Republicans no less than the Democrats. It appealed to white workers equally on the basis of anxiety over economic decline but also on the basis of prejudice, the loss of class status, and the promise of a return to class collaboration—a new deal, if you can pardon that usage, with a responsive nativist-oriented ruling class. It promised, in other words, rule by like-thinking CEOs who can be relied upon to restore prosperity within the confines of a retro 1950s-like social order that erases the gains of women—right down to basic bodily autonomy—and minorities. In that regard, Trump will refashion the civil service, the permanent government bureaucracy, on a purely political basis, essentially ending the primary path of upward mobility for minorities who cannot be relied upon to pass a political litmus test. If proof is needed, see how a tea-party Republican such as Scott Walker could decimate the civil service in Wisconsin, and then tweak that example to fit Trump’s outsized predilections. The ever-malignant Newt Gingrich has already floated that prospect.

The nominal Republican Party has been effectively transformed into a white nationalist party and if it succeeds in raising Rust Belt white incomes and economic security on that basis, while checking the aspirations of Blacks, Hispanics, and women, it will have legitimized and institutionalized that transformation.

The Democratic Party has not merely lost, it has discredited itself. It is an empty vessel, unable to defend the living standards of the multi-ethnic American working class. It is a party of split loyalties, in which workers, women, and minorities are played against one another while the common interests of all take a back seat to corporate priorities. And the corporate priorities they take a back seat to are precisely those global, financial, and tech sectors that are decimating living standards and feeding the nationalist revolt.

Socialists need to take our case for independent politics into the mass organizations that we inhabit, to argue that the movements together already constitute an incipient party fully capable of financing a political apparatus free of corporate influence and of fielding a willing and qualified host of candidates on that basis. The path to independent politics resides in the first instance in breaking apart the Democratic Party, now in shambles, and moving out decisive sections of its base. Trump is well on his way to having destroyed the two-party system as we have known it. His victory has given us the latitude, and a raised platform, to amplify our case that the DP cannot and will not serve as an effective bulwark against reaction. We need an opposite pole of attraction—a movement for a new party—that arises organically from the experienced cleavages and contradictions of society.

Trump has started the political realignment in this country. Social movements, labor being central, can stay loyal to the Democrats and cave, or they can find their way to political independence and make a credible appeal to Trump-voting workers to jump ship on the basis of class solidarity and build a society directly centered on our common needs.

Leave a Reply