This article and its title are based on a presentation made at the Mapping Socialist Strategies Conference, hosted by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung–New York Office at the Edith Macy Conference Center, New York, August 1-4, 2014.

This article and its title are based on a presentation made at the Mapping Socialist Strategies Conference, hosted by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung–New York Office at the Edith Macy Conference Center, New York, August 1-4, 2014.

2010-2014: The Establishment of Austeritarianism as the “New Normality” and Its Lethal Consequences

Although signs of financial and fiscal instability became more than evident in the last decade, the global crisis officially struck Greece in 2010 under a government of the Panhellenic Socialist Party (PASOK), the forty-year-old social democratic party led by George Papandreou. Papandreou’s was the first eurozone government to invite the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to interfere in Greece’s internal European Monetary Union affairs through the formation of the troika (the IMF, the European Union, and the European Central Bank).

During the period of the implementation of the first “Memorandum of Understanding” with the troika (May 2010), the government quickly understood that it would be almost impossible to maintain social peace and consensus while applying the barbaric austerity provisions of this framework. That’s why it decided to unleash an unprecedented smear and terror campaign against its own citizens. As always, major corporate media immediately became the pioneers of this new neoliberal crusade. Their main argument was that the application of the memorandum was the only solution to avoid an imminent Greek exit from the eurozone. They embellished this narrative by building up a sense of collective guilt: The crisis was presented as a “Greek particularity,” because a) Greeks had been living beyond their means; and b) public spending had grown excessive due to an “over-sized,” “non-efficient,” and corrupt public sector. The same arguments against the Greek people were used—mainly by German populist media (Bild, Focus), but also by the rest of the governments and media—against the so-called PIIGS states (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain), even as the other governments were trying to convince their own citizens that their countries would never face similar problems under their rule.

Very soon it became more than evident that the crisis was neither a “Greek particularity” nor a consequence of excessive public spending because of an over-sized public sector (an official re-registration of civil servants demonstrated that the Greek public sector was below the European average).

What really happened was that Greece was used as the first guinea pig for an unprecedented biopolitical experiment on the new, universal model of “EU advanced competitiveness” (that is, the violent redistribution of wealth and power from bottom to top, the transfer of the commons and public services to the private sphere, and the abolition of fundamental social rights and services).

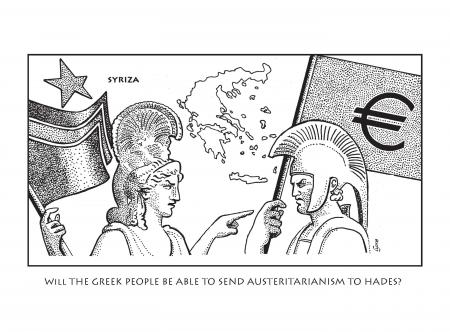

This is the new status quo of “austeritarianism,” encompassing the extensive violation of national constitutional rule and parliamentary procedures, the decisive role of unelected and uncontrolled bodies, and widespread violation of popular and national sovereignty. The neoliberal strategy has shifted from consensus to authoritarian enforcement and blackmail.

As official figures demonstrate, the real aim of the austerity strategy has never been the improvement of public finances and the control of sovereign debts. Rather, the aim of the memorandum strategy is to introduce this new state of normality in the European Monetary Union and EU states: Greek wage earners and pensioners have lost 40 percent of their annual income in the four years of the memorandum regime. At the same time, the right to collective contracts has been abolished; direct and indirect taxes (VAT, property taxes, and so on) have increased dramatically, especially for the lower and the middle classes; while common goods, strategic public services, and public assets and natural resources are under an extensive program of scandalous privatization.

The results of this policy are:

a) The transformation of a financial crisis into a crisis of public finances: 230 billion euros have been offered in cash and guarantees to rescue and re-capitalize the Greek private banking sector since 2009.

b) The dramatic deterioration of the economy, since super-austerity forced the country deeply into recession for six consecutive years (a phenomenon seen previously only in states engaged in warfare), while the Greek public debt as a percentage of GDP rose from 129 percent in 2009 to 175 percent in 2013 (compared to about 90 percent for the EU as a whole), and, according to the annual report by the Levy Institute, it will reach 200 percent by the end of 2015 if the same policy is maintained.

The Rise of the Radical Left: Sociopolitical Alliances,

Popular Resistance, and

the Phenomenon of Syriza

After four years of austeritarian rule, the violent “proletarianization” of the lower and middle classes has created a social environment of humanitarian crisis in Greece. The general unemployment rate is approaching 30 percent, while the youth unemployment rate is approximately 60 percent, with 1.6 million total Greeks currently without employment. At the same time, Greece is recording an explosion of homelessness and suicide, while a third of the general population has lost access to social security and free health care, including children’s access to free vaccinations, and so on.

This humanitarian crisis has led to an unprecedented rupture in the formerly hegemonic sociopolitical bloc and the dominant relations of sociopolitical representation, and consequently to the unprecedented increase in the social, political, and electoral appeal of Syriza.

In the two historical electoral battles in May and June 2012, the radical left coalition of Syriza was chosen by the vast majority of anti-memorandum and anti-austerity voters, in spite of many other heterogeneous political forces that expressed anti-memorandum, anti-austerity, or even anti-capitalist positions, including the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), the newcomer right-wing populist party of the Independent Greeks, the neofascist gang of the Golden Dawn, and even some electorally insignificant extreme-left parties and coalitions.

In the first electoral battle, on May 17, 2012, Syriza obtained 16.8 percent of the vote and became the second largest political force in the national Parliament. During the following weeks Syriza rejected any negotiation involving joining a government coalition with the right-wing party of New Democracy or the social democrats of PASOK, whose tactic was to entrap our coalition into an austeritarian government of so-called “national unity” or “national salvation.” Syriza’s stance led to the collapse of negotiations and to new elections on June 7, 2012, with Syriza increasing its share of the vote to 26.7 percent with 71 members of parliament elected, thus becoming the first party in all traditionally blue-collar and lower-middle-class districts and amongst the youth, but unfortunately failing to achieve a plurality by a very small margin of 2 percent. It was the first time since 1958 that a party of the alternative left (that is, to the left of social democracy) became the major opposition force in the Greek Parliament.

But if June 7, 2012, was a day of a great political and electoral rupture in the contemporary political history of Greece, May 25, 2014, was a day to remember for all generations of Greek left militants: for the survivors of the anti-Nazi resistance (1940-45) and the civil war (1946-49), for our parents’ generation of the student movement against the military dictatorship (1967-74), but also for our generation, which has built its own ideological and political identity through the anti-global, civil-disobedience movement and the social forum process. It was a day to remember because the left actually won. Syriza won in the European elections. In so doing, it became the leading political power in Greece and forced even some of the corporate media’s most fanatically neoliberal, hardliner talking heads to start speaking of “the next government in waiting.”

The electoral victory of Syriza in the European elections confirmed a massive overthrow of the political balance of forces in Greek society through a process of social and political battles that began with the submission of the country to the supervision of the troika; but it was not per se a natural or deterministic development.

The consequences of the simmering capitalist crisis of accumulation have produced completely different political outcomes across Europe, with only a single common point, which is the explosion of popular discontent. The crucial issue is that while in France or Great Britain popular discontent has been expressed and represented by political formations of the populist extreme right, in Greece, but also in Spain and Ireland, alternative left and progressive forces have won crucial battles for the representation of the popular classes.

Let us try to describe the main reasons and distinguishing characteristics that allowed Syriza to become the new counter-hegemonic political project in Greece and the first post-communist, radical-left party to compete for power in a European Union member state.

Syriza is a child of the social movements. It was initially created as a coalition in 2004, following five years of common struggles and dialogue of various radical-left forces within the framework of the emerging local, national, and international resistance movements. Our coalition was created as a political experiment of unity through diversity; as a common attempt to overcome the historical, ideological, cultural, and political fragmentation of the postwar era; and also to express and integrate the demands and aspirations of the various social resistances in the arena of central political and electoral battles.

During the last decade, Syriza has been ever present in social struggles, from traditional workers’ and students’ movements to questions of identities, without faltering when facing possible political costs. Recent highlights and turning points have been the organization of the Fourth European Social Forum in Athens (May 2006), which brought 100,000 citizens into the streets of Athens; the victorious educational movement against the creation of private universities (2006-07); the nationwide youth revolt in December 2008, following the murder of teenager Alexandros Grigoropoulos by a police officer; and even a series of local environmental movements, since Syriza, and to be more accurate its main predecessor party “Synaspismos,” was the first force of the Greek left that incorporated the “red-green” agenda in its identity as early as the 1990s.

During the last years of the crisis, Syriza has also upgraded its social-mobilizing capacity and outreach. In May 2011, after an already long series of general strikes by trade unions, we experienced the emergence of the Greek version of the Occupy movement, the Movement of the Squares, which started and was mainly centralized in Syntagma (Constitution) Square in Athens.

The development of the Movement of the Squares in Greece was a turning point that triggered rapid political developments. The outburst of social protests forced George Papandreou to resign and to deliver power to a government coalition of social democrats, conservatives, and right-wing populists, led by an unelected technocrat, the former general manager of the Bank of Greece, Lucas Papademos. The unprecedented endurance of the movement against police repression maximized social pressure against the memorandum strategy and politicized thousands of lower- and middle-class citizens, who realized that there cannot be personal solutions to collective problems.

Syriza—not accidentally, but because of our prior collective experiences from the new social movements—demonstrated efficient political reflexes. At a time when the leadership of the Greek Communist Party denounced the Movement of the Squares as a “pseudo-movement manipulated by the system and oriented to petit-bourgeois demands,” Syriza joined all committees and workshops in the squares, helped in organizing the resistance against police repression, and tried to politicize the debates in the popular assemblies, not in a vanguardist way, and not with Syriza flags and banners dominating the squares, but with an open mentality of listening and becoming “contaminated” with people’s aspirations.

From Social Explosion to

Political Change: The Battle

for Hegemony and Power

In April 2012, when the opinion polls gave Syriza less than 8 percent, we made the decisive step: we called for the unity of all Greek left and progressive anti-memorandum forces and in so doing became the first left force to put the question of gaining power on the table. Already at that time, Syriza’s position of seeking the establishment of a new coalition of power and an original narrative for a government of the left, although still not possible according to the polls, had the characteristics of a necessary and realistic utopia.

A radical act, as Slavoj Žižek would say, is an act that poses by itself the conditions for its completion. It was this stance that turned the social explosion of 2011 into a will for radical political overthrow that today advances to completion.

In July 2013 Syriza organized its first Congress and transformed itself from a coalition of 18 parties and organizations into a unified, multi-tendency, radical and democratic left party.

Nevertheless, the question of building a new historical bloc of sociopolitical forces that will confront, as the next government of Greece, rival powers at a national and international level, remains of utmost and central importance for us, as we today escalate our united initiatives against the never-ending austerity and privatization programs, in the direction of forcing our current disastrous government coalition to leave office and allow the people’s verdict to be expressed in favor of the first popular unity government in the political history of Greece.

Because, as Syriza leader Alexis Tsipras wrote in an article in August, we very well comprehend that

The process of the conquest of state power will be a long process of struggle and conflict, the outcome of which will depend on the ability of Syriza to achieve the broadest possible consensus and create the broadest possible social and political alliances around specific dilemmas that will arise.

Our first priorities in this process, to which we have already publicly committed ourselves, are the cancellation of the memorandum and the overthrow of austerity, in favor of a program for the restoration of fundamental social services, the re-establishment of fundamental social and workers’ rights, public intervention in the banking sector, and the productive reconstruction of our country. A successful confrontation of the humanitarian crisis will restore faith and hope among popular social strata even outside of Greece, and thus will reinforce social support and international solidarity for our fight for a European agreement on the abolition of a large portion of public debt and the full renegotiation of loan agreements between Greece and its lenders.

We are aware that the dominant political and economic system will not leave Syriza undisturbed in this enormous struggle of subversion. For some time, many different centers of power have been plotting to prevent this historic political development. They orchestrate the bullying of lower- and middle-class citizens through the mainstream media. They pose false dilemmas and even plan, in advance, a slippery terrain that restricts the space for maneuvers for a future government of the left; and of course they offer everything they’ve got to the reconstruction of the political space of the pro-austerity center and center-left, in order to function as a buffer and a bulwark to the rise of Syriza and the change of the sociopolitical balance of forces.

Their objective is either to re-create a large political “central” pole that will popularize the memorandum policy behind a progressive facade, or the establishment of a faction that will play the role of a bilateral interlocutor in order to push Syriza to reduce its programmatic commitments and integrate itself into the dominant political power bloc.

This strategy of our opponents for the revitalization of the center and the center-left space cannot leave us indifferent in the name of a supposed ideological purity or a distorted class prioritization of interests, because a necessary condition for the left to serve the interests of those “from below” is to prevent the plan of the opposing power bloc from degrading or forcing choices of incorporation.

The only way to prevent this reconstruction process is an open policy of alliances—the pursuit of the widest possible convergence of the subordinated classes and political forces that recognize the impasse of the applied austerity policy, a convergence based on a program for the overthrow of the neoliberal memorandum policy and aimed at leading Syriza and its allies to the winning of an absolute majority in the next national elections.

Of course, the assumption of governmental power even with an absolute majority does not automatically mean the conquest of state power. This process will be a long one of struggle and conflict, the outcome of which will depend on the ability of Syriza to extract the broadest possible consensus and create the broadest social and political groupings around specific dilemmas that will arise from the same programmatic commitments, but also from the outcome of previous conflicts.

By the term “overthrow of austerity” we do not simply mean an increase in salaries through governmental mandates, but ultimately the increase of the bargaining power of the working classes and eventually the conquest of power by them, since power is nothing more than the ability of a class to meet its specific interests.

This is the main guideline of the policy of Syriza, which at the same time refuses to pursue the fantasy of social harmony of social-democratic inspiration, which has only led to defeats.

One could argue, of course, that this path is full of dangers. Allow us to end by recalling one of the brightest minds of the Greek and the European left, our very own Nikos Poulantzas, who wrote that the only way to avoid the possible “dangers of democratic socialism” is “to stay put and be subordinated to the supervision of advanced liberal democracy.”

Sorry, but we’ll pass, because we’re not a religious sect isolated on a ranch in the desert; we’re militants of the left of the twenty-first century, dedicated to our historical mission of social change.

Leave a Reply